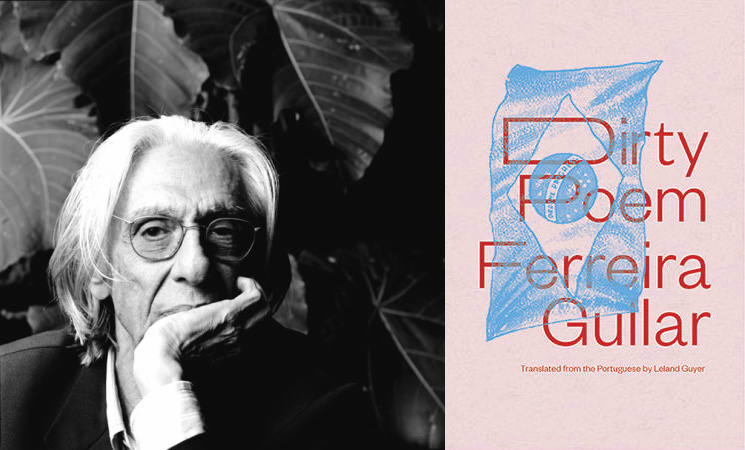

Much has already been said about exile. Losing a country or losing a home is “like death but without death’s ultimate mercy,” “a kind of ripping apart,” “a condition of terminal loss.” Ferreira Gullar wrote Dirty Poem (newly translated by Leland Guyer for New Directions) in 1975 in Buenos Aires, while in political exile from the Brazilian dictatorship. Like the author himself, the speaker of Dirty Poem imagines his return home, an attempt to recover the São Luís do Maranhão of his childhood.

The opening stanzas of this 80-page poem are filled with gaiety and fond memories of youth in the northeast region of Brazil. But just a few pages later, the speaker “preaches subversion of political order” and is banished to Argentina. In a fine translation from the Portuguese, Leland Guyer captures the richness of language of Gullar’s poetry—from local idioms to the language of displacement. The book culminates in saudade, alienation, and decay.

The unnamed speaker travels up and down the street, retelling the history of the workers of overcrowded factories, abandoned railway cars, gorgeous and depleted forests and rivers, birds who live in silver cages, women who were murdered by their husbands, indigenous peoples who were displaced and enslaved, and Baixinha’s “suburban”/“subhuman” nights. Gullar’s Brazil is both beautiful and aching, degraded and dust-covered, and his tone shifts both in and out of nostalgia and his discontentment with the life he has left behind. The speaker longs for Brazil and resents Brazil, all at once.

In his essay “Reflections on Exile,” Edward Said writes: “[Exile] is the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home: its essential sadness can never be surmounted.” Loss is central to Gullar’s exploration of his relationship with his “true home.” He describes leaving home as “an apprenticeship to death: […] our home / full of our voices / now has other dwellers: you’re still alive, and you see / that you didn’t need to be here to see / The houses, the cities, / are just places through which / we pass through.” The speaker and his home are so far apart that he becomes indifferent to the other lives that occupy the places he once knew. He describes seeing the city from up high:

those dingy red-tile roofs

of our small city

that

someone flying in from the USA

can see

between the dirty mouths of two rivers

down below

looking like forever. But

the orchard on Cajazeiras Street? The Shits and Bones /

Cistern? The Bishop’s Fountain? Newton Ferreira’s

grocery store?

The hypothetical Braniff

passenger flying so high

cannot see any of these things.

Here he reflects on the nearsightedness of the United States’ involvement in the Brazilian coup d’état, but he also expresses fear of losing sight of his own home. The city is reduced to a river, a street, a roof, a plaza—and by the pain of the loss of familiarity and nuance. Milan Kundera writes about a similar feeling of estrangement upon the return home in his Testaments Betrayed:

People generally think of the pain of nostalgia; but what is worse is the pain of estrangement: the process whereby what was intimate becomes foreign. We experience that estrangement not vis-à-vis the new country: what was foreign becomes, little by little, familiar and beloved . . . Only returning to the native land after a long absence can reveal the substantial strangeness of the world and of existence.

The familiar becomes foreign. The speaker of Dirty Poem becomes an outsider in his own home. But he never gives up on his beloved São Luís. Despite the depth of his uprootedness, he eventually realizes the city is almost unchanged and that all the places where he walked will always be down there.

It’s particularly hard for me to write about nationality and politics in Dirty Poem, because the book brings to the surface my own grievances with my homeland, as someone also born in the northeast region of Brazil. The poem’s necessity makes me bitter.

Edward Said writes that exile is “a condition legislated to deny dignity—to deny an identity to people.” Dirty Poem is a bold, quintessential text on exile precisely because it reveals that an identity lies very deep. The poem ends with the knowledge that a city can’t leave its people, for its history, its landscapes, its vices, its speed and systems remain “in the man / who is in another city // but there are many ways / an object / can hold another.”

There is both tragedy and comfort in the fact that Brazil is outside the speaker as well as inside. He is stuck in the in-betweenness, confined by the city’s ominous presence and yet liberated by the nourishment of familiarity: “the city’s in the man / the way a tree flies / in the bird that leaves it.”

***

Bruna Dantas Lobato is an editor-at-large for Brazil for Asymptote. She is a Fiction MFA candidate at New York University, and a graduate of Bennington College. She grew up in Natal, Brazil.