One Hundred Shadows, the debut novel of Hwang Jungeun, is a tilt toward the borderlines of society, where the disconnected and the dispossessed attempt to make a home; it is a ferroconcrete dream version of Seoul with a wistful languor, desperate to prove that even in the murkiest crannies of the city, there are surges of fellow-feeling, or snatches of shared joy, that can suddenly break through the hard-bitten top layers and bloom.

Working as an assistant at a repair shop in a sprawling, cavernous electronics market, Eungyo finds herself drawn into an idiosyncratic community of Seoul’s twilight periphery. There is Mr. Yeo, her boss, who works until the crack of dawn and adores sweet red beans with shaved ice; there is the itinerant and rambling Yugon, who puts his faith in the lottery rather than in other people; and there is Mujae, who, like Eungyo, abandoned his formal education and also works as an assistant. Eungyo and Mujae meet occasionally to eat noodles and drink beer, and as the demolition of the electronics market looms alongside the regeneration of the neighborhood surrounding it, the two come to develop a timid intimacy which leans clumsily into a love formed from the outside looking in, and they discovered themselves synced into one orbit—and on the edges of observing their shadows rise.

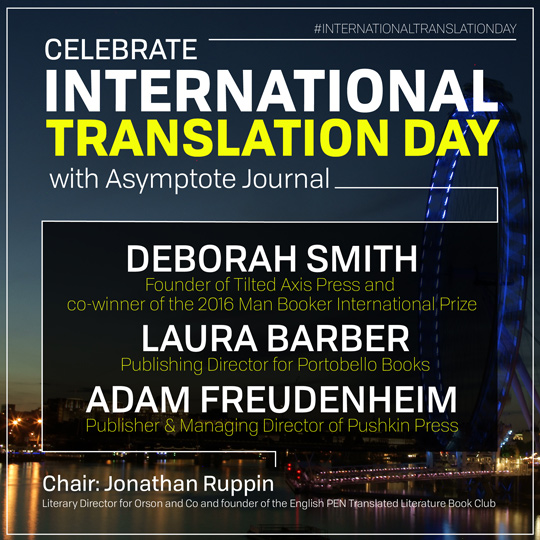

Ahead of her UK tour, Hwang Jungeun sat down with Asymptote to discuss One Hundred Shadows, which was translated from the Korean by Jung Yewon and published by Tilted Axis Press on 3 October.

Hwang Jungeun’s replies appear below both in the Korean and in English translation by Deborah Smith.

Read an excerpt of the book here.

M. René Bradshaw (MRB): One Hundred Shadows takes place largely in an electronics market in central Seoul—an impoverished area targeted by rapid regeneration efforts. Which specific locations of the city inspired the novel’s settings? The electronics market is so pervasive, its function and internal dynamics so important to the main characters’ lives, that it almost acts as a character itself within the story. Is there a personal anecdote attached to a similar electronics market?

Hwang Jungeun (HJ): There are two locations which form the background to the electronics market which appears in this novel. One is a large electronics market in Yongsan, an area in central Seoul. In the process of this area’s redevelopment, there was an incident in which five evicted residents and one armed policeman were killed. This happened on the morning of January 20, 2009. The conglomerate that was heading the redevelopment construction employed civilians known as ‘construction thugs’. They entered the building earmarked for demolition, whose residents had been protesting their eviction, en masse. While the residents were trapped on the roof, they lit a fire on the ground floor and fired water cannons. Though the police of the South Korean government were there in the hundreds, they protected the ‘thugs’, and actively encouraged the illegal actions committed by them. In the final moments, they implemented something known as the ‘Trojan horse operation’, used to suppress protests. It was an operation which used a crane and container to demolish the lookout tower which the residents had constructed on the roof. The moment armed police swarmed onto the roof, a huge conflagration broke out in the tower. Six people who were unable to escape from the tower died. This was all broadcast on the news and many people witnessed the moment of the fire breaking out in real time. I was one of them.

After the incident, the place became known as Namildang. I wrote this novel from summer to autumn 2009. I wrote before the sun went down, then around sunset I went and held a protest in front of Namildang. After the fire, the bereaved families gathered at the building and almost every day a violent altercation occurred due to the use of police force. That place, and the things that happened there, were so miserable, I wanted to make something warm. I thought that it was the only thing I could do. And so I wrote this.

Secondly, there is a place called Sewoon Electronics Market in Jongno, which is both the old and current centre of Seoul. Its eight long buildings were completed in 1968, and stretch from Jongno to Toegye-ro, and the first of these buildings, which is the modern market, was demolished in 2008. Even when the disaster occurred in Yongsan in 2009, demolition was still going on. My father has been repairing audio equipment for forty years in the second of Sewoon Market’s buildings. The setting around the electronics market which appears in the novel, including Mr Oh’s repair shop, Omusa, and the transformer workshop where Mujae works, are all descriptions of places that were there or still are.

READ MORE…