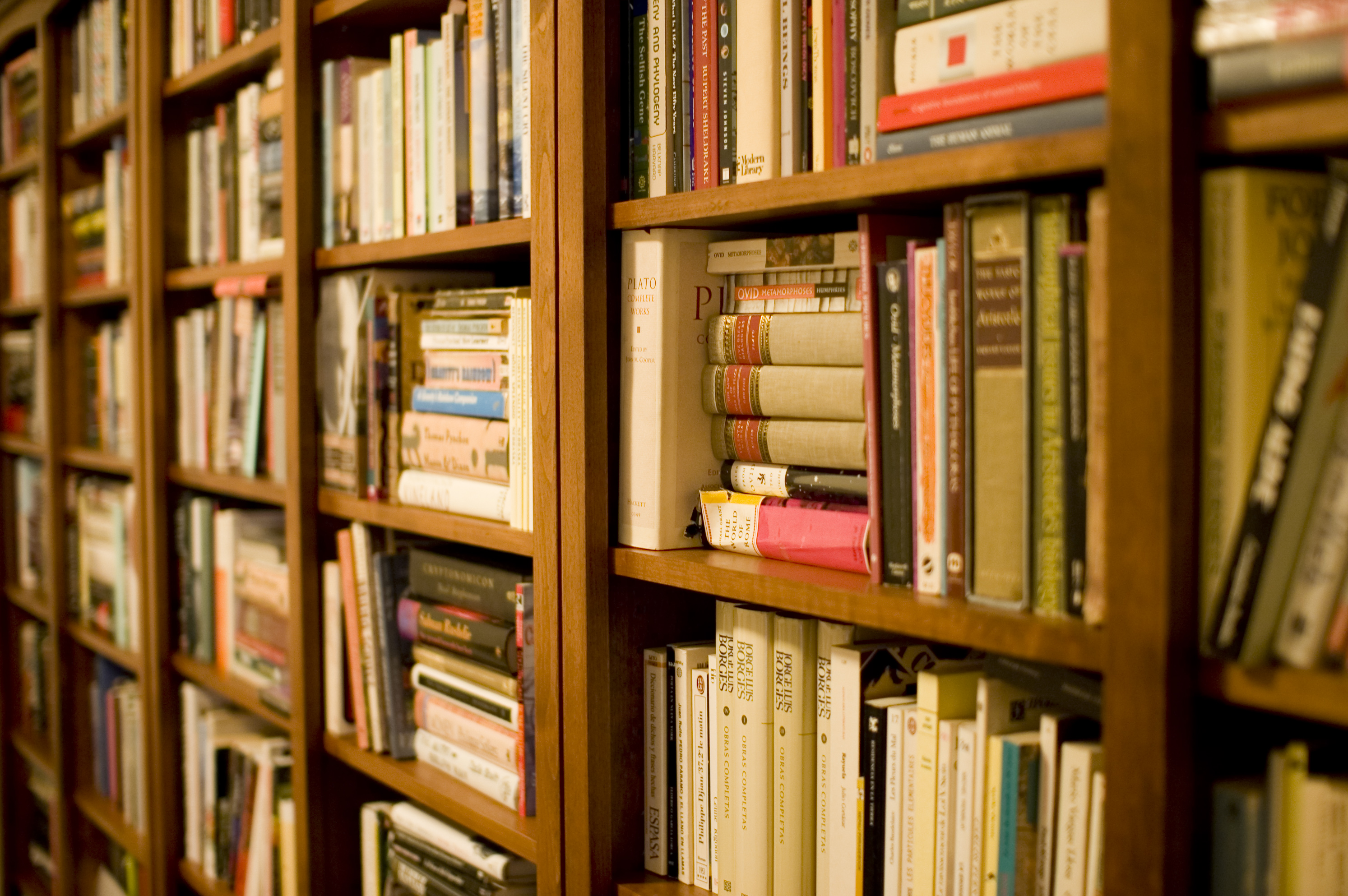

Translator’s note: The story was inspired by an accident that took place on 4 February 2008, in which the owner, Law Chi-wah, of a famous independent bookshop in Hong Kong, Ching Man Bookshop, was buried alive by almost two dozen boxes of books when he was sorting the books in the bookshop’s warehouse. Law Chi-wah was a veteran Hong Kong culturati. He took over the running of Ching Man Bookshop in 1988. Ching Man Bookshop suspended its retail business in 2006 because of rental issues, and its book stock was moved to a warehouse while its publishing business continued. A new location for reopening the bookshop had already been arranged before the accident. Ching Man Bookshop was permanently closed upon the death of Law. The story also pays tributes to independent bookshops in Hong Kong, as running an independent bookshop is a very difficult task in the city with its high property rent. More independent bookshops have moved to higher floors in old buildings or even closed down due to financial stress.

***

Deng3. Cantonese for hit, throw, strike, smash or toss with force

At some point today, a pile of books fell on my head. According to the Society’s memorandum, if one of its members is hit on the head with books, that person is to report, record, and file his case immediately and go to the designated location for emergency treatment. The European grammar of the memorandum’s written Chinese phrases this in the passive voice as “being hit with books,” as if there is another subject, such as a person, who is doing the throwing. But this time, books simply fell on my head. The books themselves were the subject. Whether I was hit as defined is hard to say; I am not good at grammar. Maybe a certain unwitting action of mine triggered, or even my long-term habitual pretense eventually led to a chain reaction, the butterfly effect, quantitative and qualitative changes etc. that caused the books above my head inevitably to fall on me at a certain time. As such, I was the one who hit myself, I become the subject who threw the books. Although in this case, to say the books “hit” me is somewhat inappropriate; they “fell on” or, better, “smashed” me. But who cares about such a semantic trifle? The fact is, books have fallen on my head. My metamorphosis is about to take place.

I hesitate to disturb comrades of the Book Preservation Society. I don’t want to cause any trouble for them. They are accustomed to hiding in the city like phantoms. With only a few exceptions, most of them don’t enjoy interacting, let alone attracting attention. Only when they occasionally bump into each other do they greet themselves timidly, like hedgehogs in winter that can only touch each other hastily, who want to snuggle for warmth but are put off by a greater fear of being hurt by others’ spines. Sorry, passive voice again.