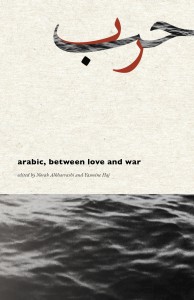

In Arabic, the word for ‘love’ (حب) is nearly identical to the word for ‘war’ (حرب), differing by just one letter. The nearness and linguistic kinship between these two words is a felicitous metaphor for the tropes examined in the poetry anthology Arabic, between Love and War, published by Tkaronto, Canada-based trace press.

Arabic, Between Love and War assembles important voices from across the Arabophone world, such as Nour Balousha of Palestine, Najlaa Osman Eltom of Sudan, Rana Issa of Lebanon, Qasim Saudi of Iraq, as well as diasporic Arab poets in Canada, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and the United States. Edited by Palestinian poet Yasmine Haj and Saudi translator-scholar Norah Alkharashi, the anthology features poems translated from Arabic into English and vice versa, a number of which have garnered accolades such as the Lambda Literary Award, Atheer Poetry Prize, Arab American Book Award, and appeared in poetry collections published in Damascus, Beirut, Juba, California, Basrah, Algiers, and beyond.

In this interview, I spoke with both Haj (in Paris, France) and Alkharashi (in Ottawa, Canada) about the anthology and the ways in which the poetry of love and poetry of war converge.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (AMMD): Congratulations to both of you on this riveting anthology, Arabic, between Love and War! How did this book come to be, and how is it particularly relevant and urgent today?

Yasmine Haj (YH): Thank you, Sam. This book is the epilogue to a workshop organised by trace press, ‘translating [x]’, in which Norah and I co-facilitated six online sessions on literary translation from Arabic. As we structured the workshop, we were drawn to the aesthetic of the words love and war in Arabic, and how the removal of one letter throws one word into its apparent opposite. We discussed the idea with the participants, some of which mentioned how tired they were of our world being discussed through the prism of war. This was in late 2022, early 2023, before Zionism heightened its genocide of Gaza and any reminder of indigeneity. We had no idea we would be editing this volume, with all its submissions, as we watched Palestine oscillate between those very two words, and other genocided lands fluctuate right along with it. Love of land, of people, and war waged upon that very existence, have been ongoing for more than a century, adding to the six hundred years of imperial annihilation and substitution. READ MORE…