Asymptote‘s latest issue hit the digital shelves on Friday, and there’s so much to read: in addition to featuring poems by the late Tomaž Šalamun and brand-new verse from Aase Berg’s Hackers, (translated from the Swedish by Johannes Göransson), you can read interviews with Ferrante/Levi translator Ann Goldstein and literary heavyweight/literary “improbability” Ha Jin. But it doesn’t end there: at long last, this issue features the winners of our Close Approximations contest, but among so many other “regular” journal offerings, it’s hard to know where to start. In true blog tradition, we’ve picked favorites from the latest release. The list, we insist, is by no means exhaustive; you really can’t go wrong at all—dig in! READ MORE…

Translations

Translation Tuesday: “A Corpse” by Hamid Ismailov

"Looking from behind his son’s shoulder to the small pile in front of them, he saw a naked arm protruding from the snow."

Let him who gives me a shadow not hold me.

You know the breadth of a star

is not equal to the embrace of the ray.

Let me go, blue holy light,

my shadow is in torment on the black earth.

Am I drunk, or is my road drunk?

The snow flows, the earth is white and black.

The word ‘I’ is a wanderer like I,

you are eternal as an icy, cracked puddle.

Did we trip over our shadow

or did the mirage melt in the icy pupil—

a roof, holding up a lamp, when the house moved.

As the day approached noon, Zamzama awoke, and walked into his smaller bathroom to wash himself for the day. The light happened to be on in the narrow room, and he stretched his hands out towards the tap. At exactly the same point, his still-sleepy eyes happened to notice a naked adolescent lying in the bath. Maybe he realised that it was an adolescent due to the fact that the whole body could fit into the bath. Maybe also due to him lying in an empty bath naked, Zamzama purposefully didn’t look in that direction, rather washing his hands with soap and distracting himself with the trickling tap. ‘Perhaps I should have knocked, although he seems to be keeping silent,’ he thought for a moment, though this thought appeared and disappeared just as fast as the flowing water, circling down the drain.

The boy indeed kept silent. In order to avoid bad luck, he didn’t want to shake his hands dry. Therefore, trying to locate the towel in his mind, he unwillingly glanced at the figure in the bath. Was he one of the unmannered friends of his son? For some reason, his vision fell onto their fluffy crotch, jumping back up to the boy’s slanted, closed eyes. Whilst rushing out of the bathroom trying to make no sound, the fact that there was no water in the bath astounded him. Had the young man fallen asleep, and if so, how could he? Was he drunk? Only having just seen his fluffy groin, he thought, are his legs a little disproportionately short? Maybe they were just going into the dark bottom of the bath… READ MORE…

Translation Tuesday: An excerpt from “Making Skeletons Dance” by Peter Macsovszky

"We’re waiting for a favourable wind in our skulls. Simon taps his forehead and grimaces."

The action of the novel takes place in one day (as in Joyce’s Ulysses and Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway). The main character is Simon Blef, a man who has emigrated to Holland, where he met his future wife, a Mexican-Dutch girl named Estrella. As he waits for Estrella, who is returning from Spain, Simon wanders into the Amsterdam pubs and starts drinking. As time passes, all kinds of memories surface from the past. There is no striking action in the novel; it is rather an impressionistic reverie with glimpses of humour and a mordant commentary on the main character’s ambition to become a writer. This novel was shortlisted for Slovakia’s most prestigious literary award, Anasoft Litera Prize, in 2011.

***

1. There’s somebody

whose refuge is a pub like this, neither filthy nor speckless, but the sort of place where a passer-by does not stay too long. Battered, creaky chairs, dust-coated wooden panelling, a slot machine. For somebody refuge means a bar counter, subdued conversation, light music, world-famous glances from bronzed faces. For someone, again, it’s a woman willing to hear the cycled effusions of pain, morning and evening. Hear them, care for them, cultivate and protect them. Fantasies of alleged wrongs and menaces. For Simon Blef, whom no misery is tormenting today and therefore he claims no concern, refuge means this Amsterdam pub, neither filthy nor speckless, scrunched at the corner of Gravensstraat and Nieuwe Zijdsvoorburgwal. From there Simon Blef gazes at the world, observes passers-by, how they borrow and steal gestures, each in a way that is both unique and custom-worn. Not quite half an hour ago he was boring through the crowds that came hurtling out from the platforms of Centraal Station and wondering whether to go left and find some quiet boozer in the Red Light District sidestreets, or if he ought to go right and cast anchor as ever in this unprepossessing drinking shop, which basically serves as an entrance hall for a hotel and restaurant on the first floor.

Simon has picked his spot by the window so as to be able to see the doings not only on the street but also by the bar counter. Encompassing with one’s gaze the largest possible segment of the world currently served up: then he feels in a place of refuge. READ MORE…

Translation Tuesday: “IN THAT PHOTO, FIX THE PIT STAINS ON MY SHIRT” by Luis Chaves

The drizzle like infinitesimal pinpricks, the sensation of __________.

Someone’s going to dream about this.

Head in the second house, the body

centered: a brick, a bar,

equidistant from two gringos.

We were about to go somewhere else

when an alarm began to signal

another reality:

“In that photo”—it tells me— “fix

the pit stains on my shirt.”

Climate change is listening

to summer’s hit song

in the winter.

A word like antiretroviral

in even the most visionary poem. READ MORE…

Translation Tuesday: Excerpt from Joost de Vries’s “A Room of My Own”

My brother put on his big, fake, photo grin, while one of Kissinger’s assistants smiled professionally and said, firmly, 'Please, just one picture'

Henry Kissinger had a flabby mouth he was fond of using to make droll comments, like calling power the ultimate aphrodisiac, an aphorism he repeated so many times people started to believe it, encouraged by his own tendency to pose for the paparazzi at dinners and cocktail parties with a platinum-blond socialite or an aspiring starlet on his arm. Looking at those photos now, you see a square tuxedo with a man stuffed into it. A bulging face, no neck to speak of, tiny eyes behind enormous glasses, classic wavy hair. And a Barbarella babe next to him in a delirious dress, her teeth bared by a smile so strained it looks like she’s putting her face through an aerobics workout.

‘Power is the ultimate aphrodisiac.’ He was referring to those women, but didn’t think his theory through enough to realise it applied to him too. In the run-up to the presidential election of 1968 he’d called Richard Nixon ‘unfit to be president’, but when President Nixon called him three weeks after winning to make him National Security Advisor, he didn’t hesitate for a moment. He too felt his knees quiver and his heart pound when faced with the true power of the White House.

‘Will you be my National Security Advisor?’

‘Oh, I will, Richard. Yes, I will.’

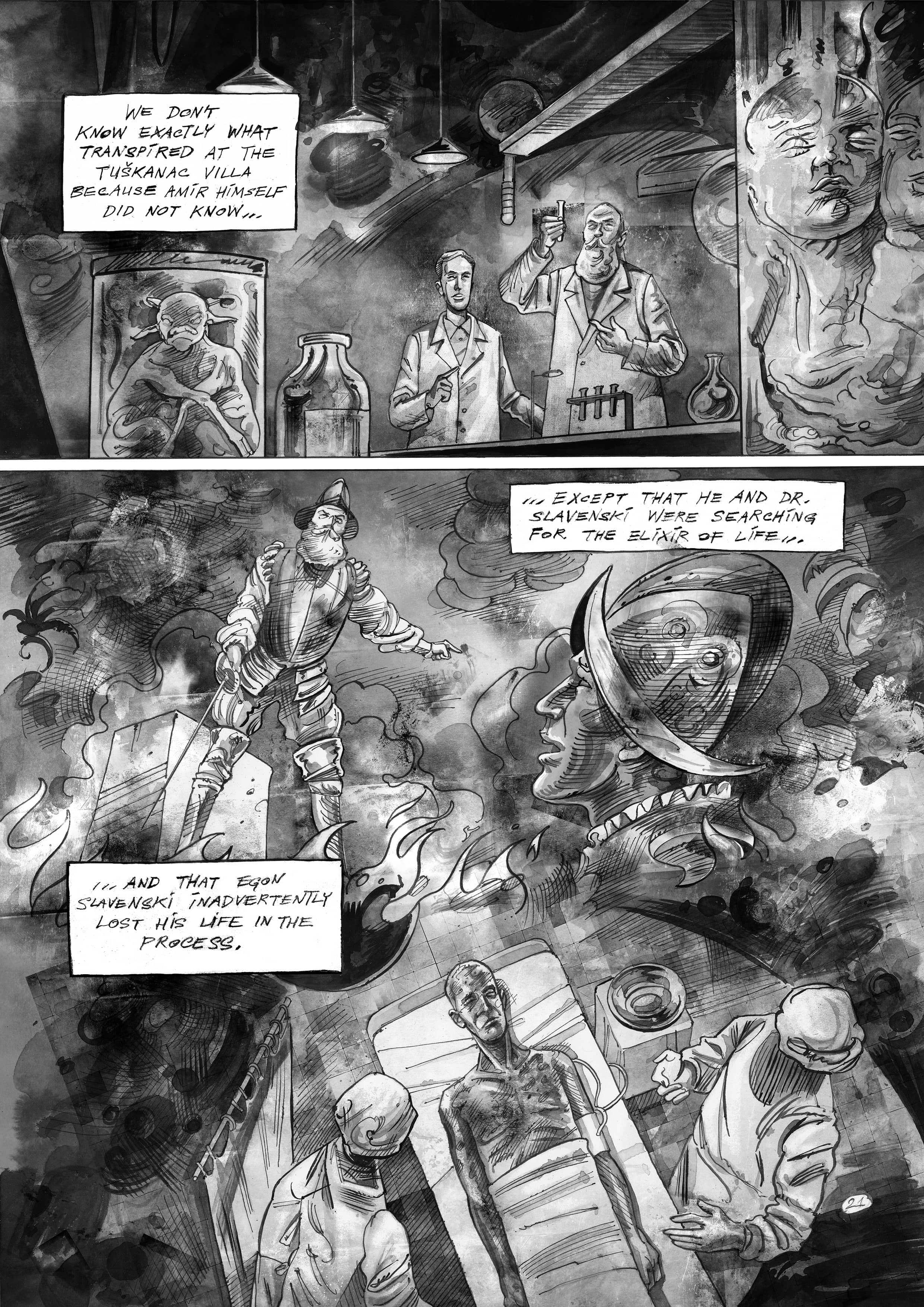

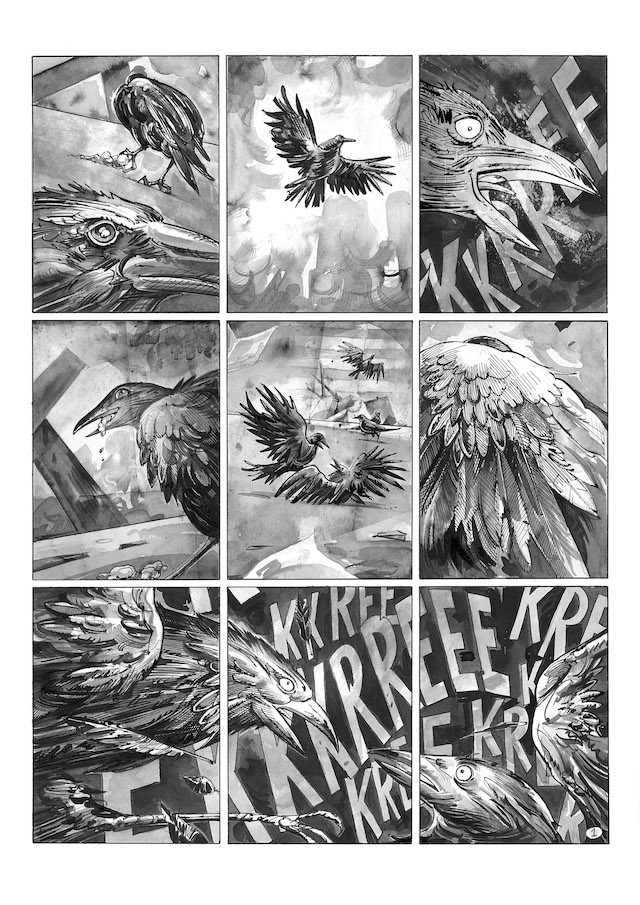

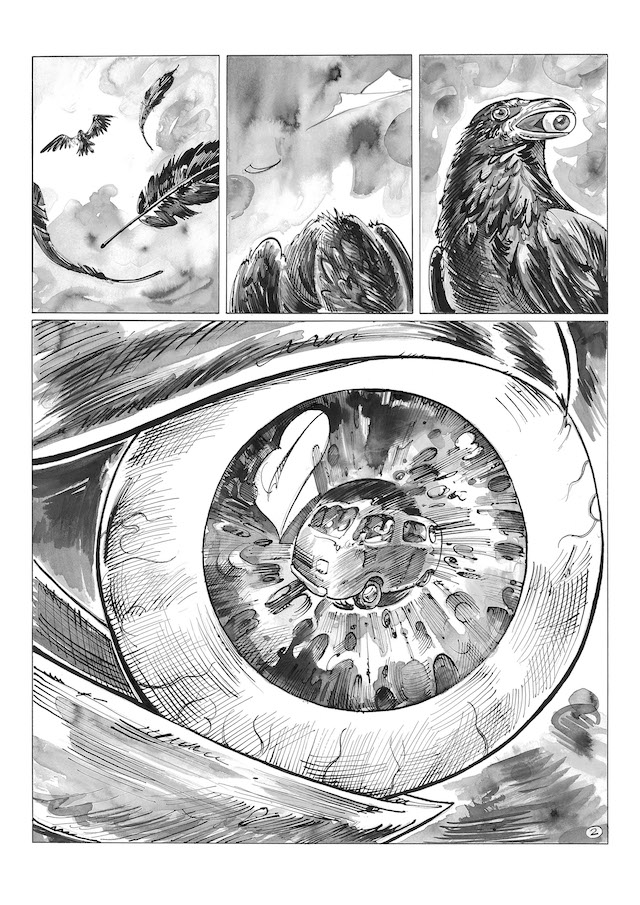

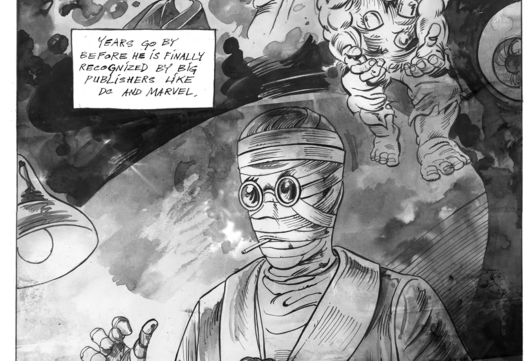

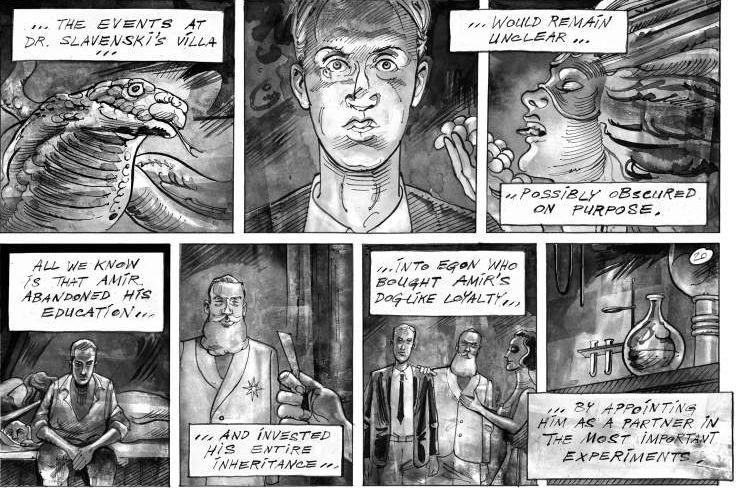

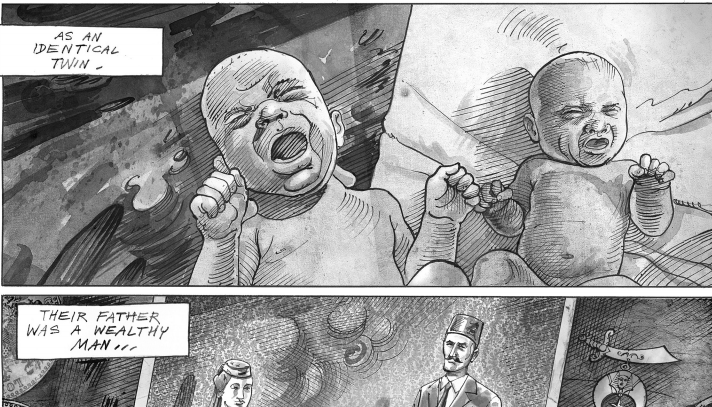

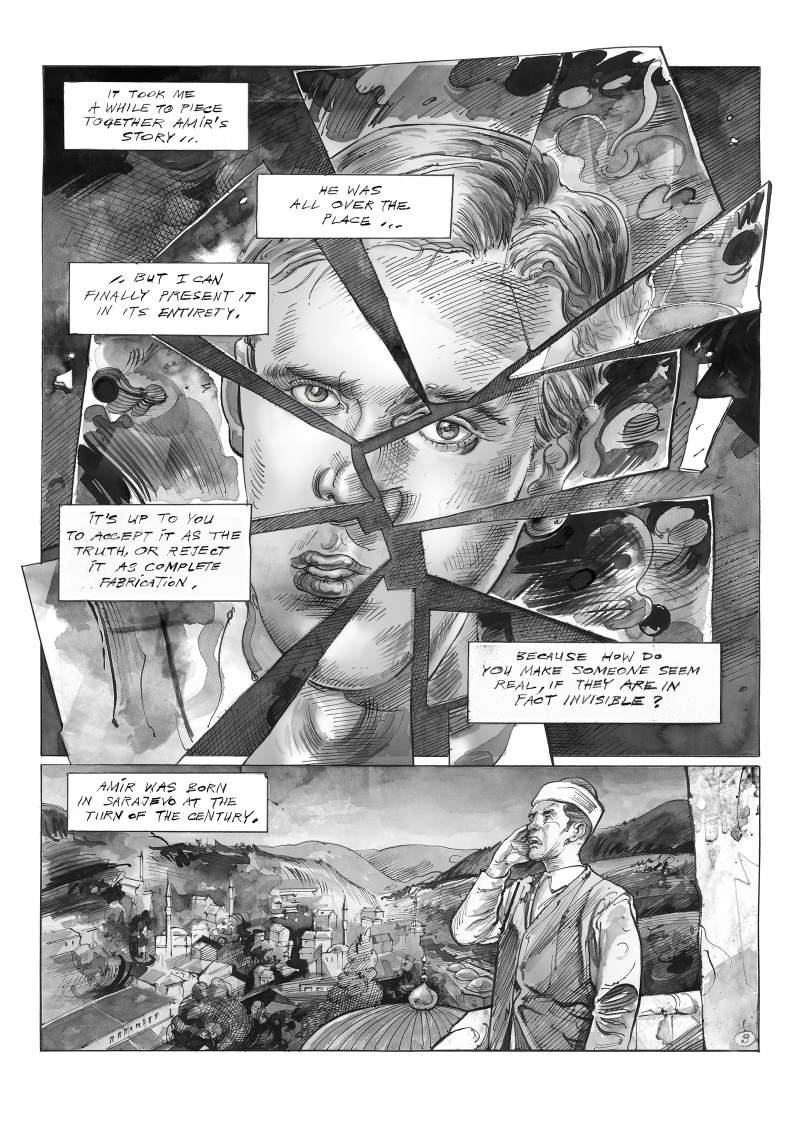

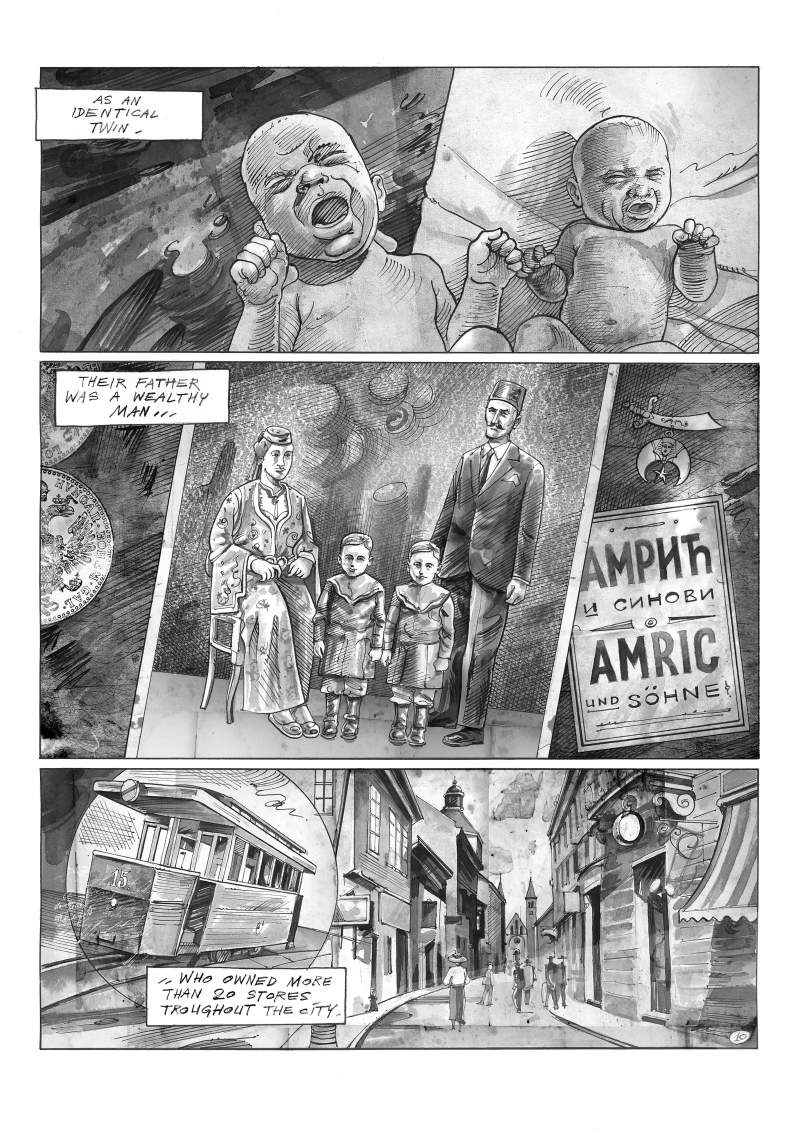

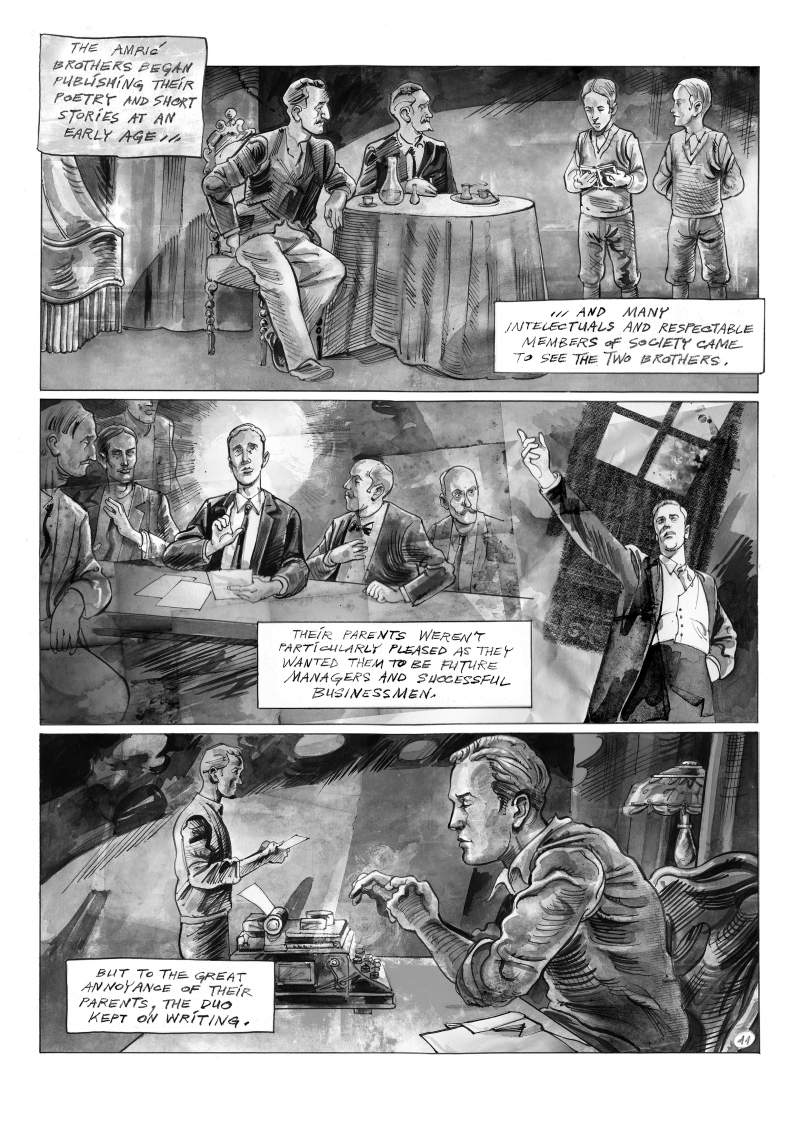

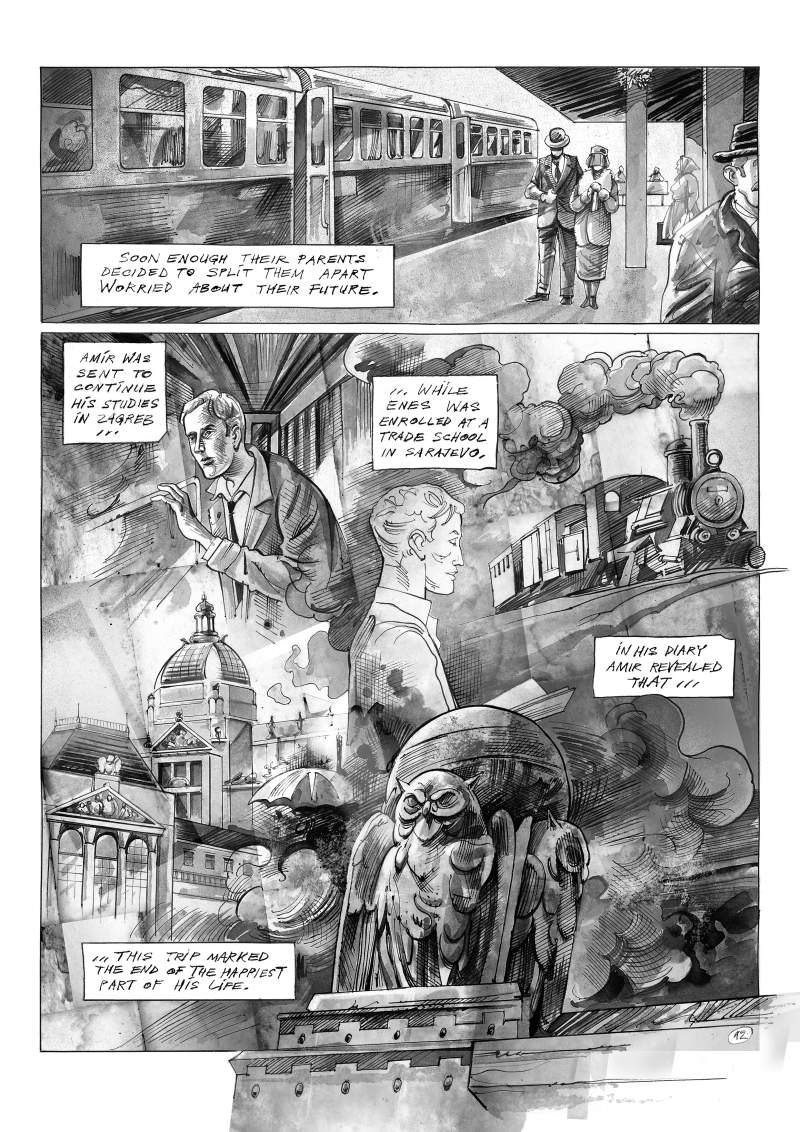

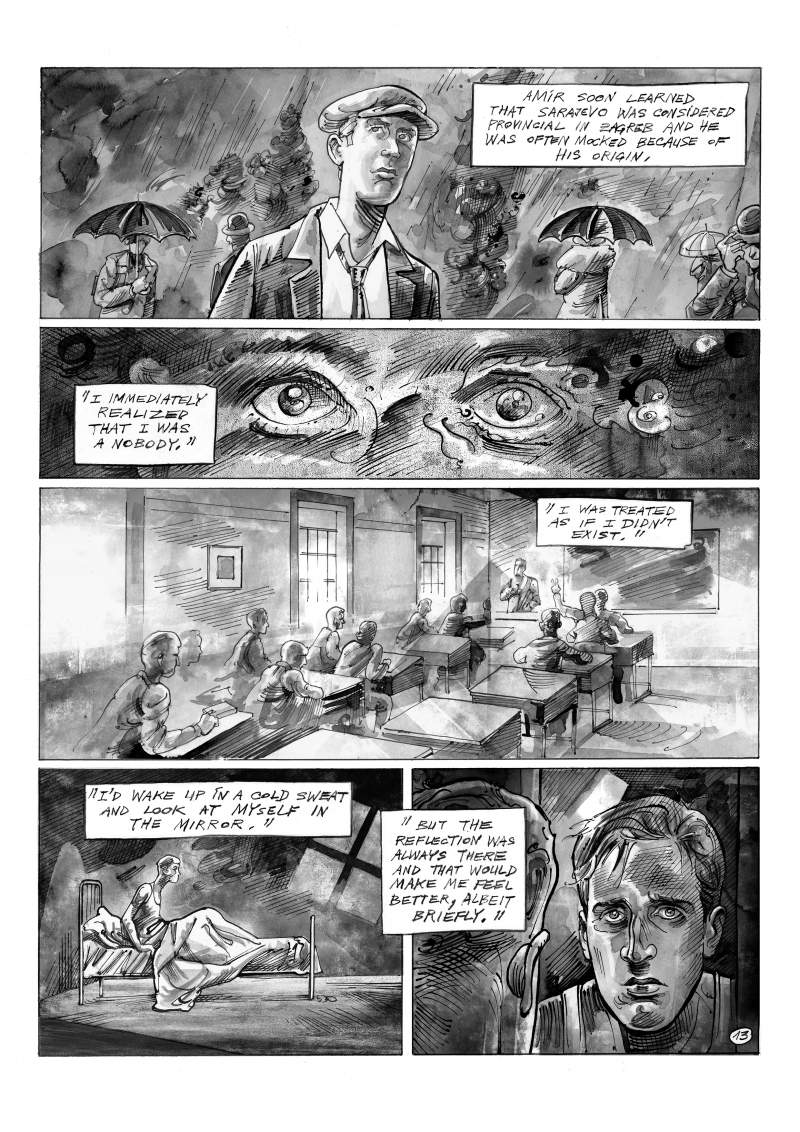

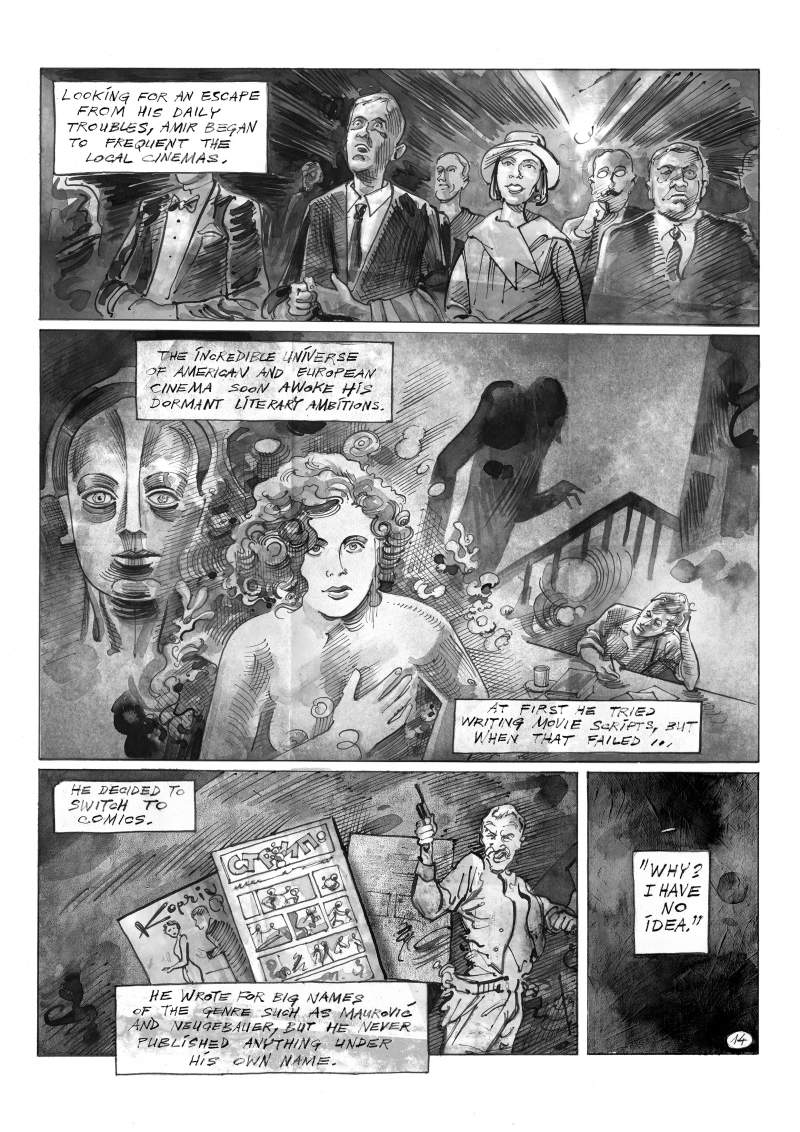

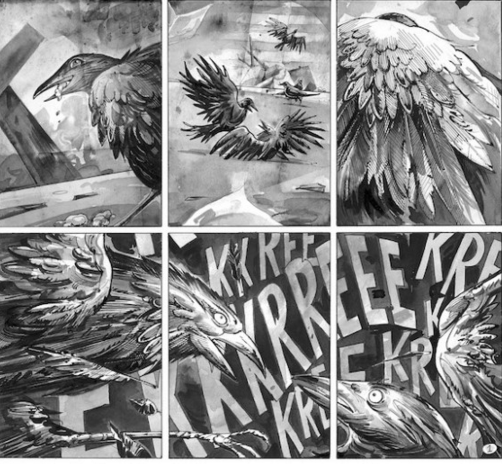

Graphic Novel in Translation: Karim Zaimović’s “The Invisible Man from Sarajevo,” Part IV

Part IV in Asymptote blog's first-ever graphic novel in translation

Translation Tuesday: An excerpt from Radka Denemarková’s A Contribution to the History of Joy

“Call the police. This is what I want to say but words won't make it past my lips, my lips hurt, everything hurts, I’m all torn like an animal.”

We mark International Women’s Day with an extract from the latest novel by the award-winning Czech writer and Nobel laureate Herta Müller translator Radka Denemarková. Disguised as a crime mystery set in Prague and mixing fact and fiction, “A Contribution to the History of Joy” (Příspěvek k dějinám radosti, 2014) is a passionate indictment of all forms of violence against women everywhere, spanning the past 70 years of history. In the extract below Denemarková puts herself in the shoes of a victim of an infamous Manchester (north of England) gang that groomed vulnerable teenagers and forced them into prostitution.

***

Chandra Namaskar, the moon salutation. This isn’t like Honey’s birthday party. Then, our classmates had swarmed around her parents‘ house sipping drinks and strutted around screaming and shouting and dancing to booming music that made the walls shake.

Here, no noise passes through the walls, only silence. Cigarette smoke and still-glowing ashes in overflowing ashtrays swallow up any trace of noise. The windows aren’t blacked out. At the door to the flat, a boy collects my mobile. I’m not happy about that. I’ve been saving up for it for a long time. This is a compulsory admission ritual. It’s for your own good, the boy says, to make sure you don’t lose it, I’m kind of like a hotel safe here, he says with a reassuring wink. We’ve both been chosen.

I tread across the thick pile of Persian carpet. There are carpets everywhere. They spill across thresholds continually like a dense lawn, sticking out their tongues under my steps. I look forward to having my pictures taken by a professional photographer. That’s what Honey promised me.

The boy ushers me into a smoke-filled lounge. A man is snogging a girl on a sofa. They’re like a classical statue emerging from the mist. The girl might be about thirteen. As they peel away from each other, tiny stones in the girl’s braces sparkle like diamonds in her mouth. The man seems old to me. They glance at me. He looks me up and down, from head to toe. The girl‘s eyes connect with mine, her stare is swept clean and empty, I can read nothing from it, then they latch onto each other again. Two glass bowls of white powder sit on the coffee table before them. The smoke and nicotine mist make me nauseous but I don’t let on, I want to belong, I do belong, I’ve made it. After weeks of soundings and failed attempts I’ve finally done it. Curiosity is making my head spin. Honey is making my head spin. Here she comes. She gives me a welcoming hug. I giggle trying to boost my courage and get rid of my fear. Honey hugs me and charms me, saying how lovely I look, in my excitement all I manage is a stutter. She hands me a bottle of chilled vodka. It’s drunk straight from the bottle here. She swings her arm around me and summons the boy who collects and stores mobiles by the door. She is bossy with him, it’s obvious who’s in charge here. That’ll be all for today, she tells him. I can’t tell if she’s talking about girls or mobiles. The boy rolls me a joint. I take a puff and shake my head. I give him the spliff back. The boy passes the joint to Honey, who sticks it in the hand of the man glued to the lips of the girl with diamonds in her mouth.

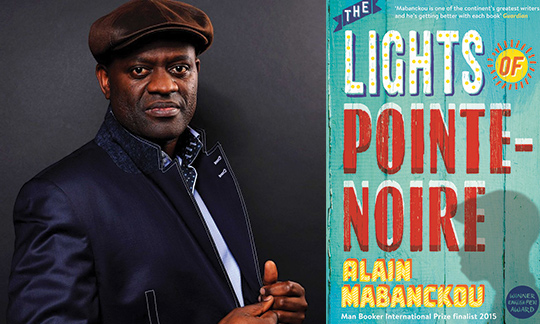

Translation Tuesday: Excerpt from Alain Mabanckou’s The Lights of Pointe-Noire

Read an excerpt from the 2016 French Voices Grand Prize-winning memoir, out today in bookstores!

My father was a small man, two heads shorter than my mother. It was almost comic, seeing them walking together, him in front, her behind, or kissing, with him standing up on tiptoe to reach. To me he seemed like a giant, just like the characters I admired in comic strips, and my secret ambition was one day to be as tall as him, convinced that there was no way I could overtake him, since he had reached the upper limit of all possible human growth. I realised he wasn’t very tall only when I reached his height, around thetime I started at the Trois Glorieuses secondary school. I could look him straight in the eye now, without raising my head and waiting for him to stoop down towards me. Around this timeI stopped making fun of dwarves and other people afflicted by growth deficiency. Sniggering at them would have meant offending my father. Thanks to Papa Roger’s size I learned to accept that the world was made of all sorts: small people, big people, fat people, thin people.

He was often dressed in a light brown suit, even when it was boiling hot, no doubt because of his position as receptionist at the Victory Palace Hotel, which required him to turn out in his Sunday best. He always carried his briefcase tucked into his armpit, making him look like the ticket collectors on the railways, the ones we dreaded meeting on the way to school when we rode the little ‘workers’ train’, without a ticket. They would slap you a couple of times about the head to teach you a lesson, then throw you off the moving train. The workers’ train was generally reserved for railway employees, or those who worked at the maritime port. But to make it more profitable, the Chemin de fer Congo-Océan (CFCO) had opened it to the public, in particular to the pupils of the Trois Glorieuses and the Karl Marx Lycée, on condition they carried a valid ticket. As a result they became seasoned fare dodgers, riding on the train top, in peril of their lives. It was quite spectacular, like watchingFear in the City at the Cinema Rex, to see an inspector pursuing a pupil between the cars, then across the top of the train… READ MORE…

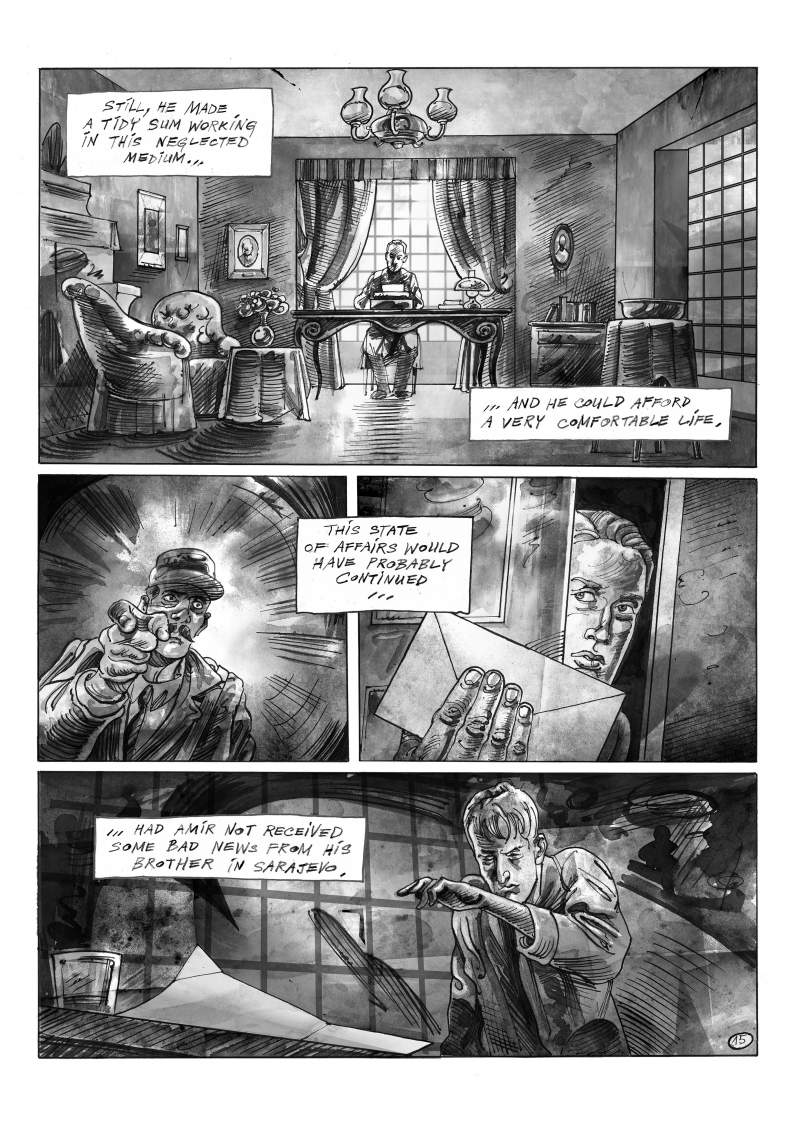

Graphic Novel in Translation: Karim Zaimović’s “The Invisible Man from Sarajevo,” Part III

Part III in Asymptote blog's first-ever graphic novel in translation

Click here for Parts I and II in this series.

Translation Tuesday: “A Fence” by Patricio Pron

She thinks, if God were a just writer, he would create a fence made of words so that his characters wouldn't wander off and wind up lost.

1.

One morning (it doesn’t really matter which, but it’s March, it’s Saturday, it’s the year 2010, it’s the twenty-seventh) a young man is jogging with his dog down a quiet street in a residential neighborhood south of the German city of Hanau when something happens—the dog runs ahead or lags behind or darts off in search of something that caught its eye and is hit by a car. When the car’s bumper strikes the dog’s ribs, the bottom of the bumper, which is particularly sharp, slits the animal’s stomach open and turns red; immediately afterward, the rest of the dog’s body is swallowed by the car, which stops after a few meters, when it’s already too late. When the dog’s owner rushes to the car and sees that the animal has been run over, he quickly calculates that the chances of saving the dog are zero; nevertheless, the animal is still panting softly and tries to stand, all the while looking up at him, its eyes nearly popping out of its head. The dog, of course, is unable to stand since its body has been sliced in half, and the dog’s owner kneels next to it and begins to pet it and whisper soothing words as tears stream down his face. The animal stops breathing seconds later, and, when the young man goes to pick up the dead body, he notices its intestines are full of Argiope spider larvae; since the young man is studying to be a veterinarian, he is able to identify the larvae on the spot, and then remembers two things he recently learned in one of his classes: first, that the females of the species simulate coitus with each other to entice the males to mate; and second, that after consummation the males release their sperm-filled sex organs inside the females and try to flee, but are typically caught and devoured by them. READ MORE…

Graphic Novel in Translation: Karim Zaimović’s “The Invisible Man from Sarajevo,” Part II

Part II of Asymptote blog's first-ever graphic-novel-in-translation

For Part I in this series, click here.

*****

Download part one, part two, and part three.

Karim Zaimović (1971-1995) was a comic strip artist and writer for the weekly magazine BH Dani in Sarajevo. During the war he hosted a radio show on Radio Wall, Sarajevo, called “Joseph and His Brothers.” At 24, he was killed in Sarajevo, in August 1995, only three months before the Dayton Peace Accords brought an end to the fighting. His stories and the transcripts of his radio shows were lovingly assembled in the book, The Secret of Raspberry Jam, by his friends and colleagues, and were produced for the stage in a play of the same name by theater director Selma Spahić.

Aleksandar Brezar was born in Sarajevo in 1984. He has worked as a journalist at Radio 202 and a translator on several documentary films and other film-related projects for PBS, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and Al Jazeera English, among others. His translations have appeared in the Massachusetts Review, Brooklyn Rail, Asymptote, Peščanik, and Lupiga. His graphic novel adaptation of Karim Zaimović’s story “The Secret of Nikola Tesla,” illustrated by Enis Čišić, was nominated for a Pushcart Prize in 2015.

Boris Stapić is a graphic designer and illustrator from Sarajevo. He studied in Zagreb, Croatia, at the School of Applied Arts and Design, and at the Academy of Fine Arts in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. He has worked at several advertising agencies as a designer and creative director. Boris has co-founded the TripleClaim Game Collective, a video game, app, and new media studio. Of the adaptation, he says, “adapting the original text was a great challenge because Karim’s stories seem to arise from an external creative impulse. They are a melting pot of ideas, obsessions and anxieties of the entire twentieth century, and a playful and engaging literary game of motifs and intimate fascinations.

Translation Tuesday: An excerpt from “Bin Bags” by Enrique Winter

No matter whether they were men or women, he had always liked the bad ones.

Every morning Brian is in the habit of washing his arsehole with balsam, the way Eugenio used to like it. The upstairs bathroom is also shared, but it’s kept clean enough, because of the big window and because he’s included in a rota that the girls on that floor had inherited from other girls. He lathers his legs, the hair’s growing back, and he asks himself how something so obvious—that if you love someone you never stop loving them, dead or alive—is mentioned neither by the people giving advice nor by those taking it. When you’ve loved someone, you’ll always love them. That’s all there is to it. He closes his eyes to rinse himself off. You can survive with that, with or without your loved ones. You don’t replace them, you add to them. He dries himself, some parts better shaven than others, and the towel keeps Eugenio at the forefront of his mind: once, Eugenio, wrapped in a towel, said he made people see what they didn’t know they didn’t want to see. Brian then demanded an explanation and Eugenio spoke at length while he got dressed about how he’d manage to provoke people who swore they were as liberal as can be.

Brian could spend a long time sitting with his eyes fixed on the back of Eugenio’s knees, while he stood cooking. They were always the beginning of something and Eugenio let him look—with one foot he could stroke his calf as though itching it, or straighten out his shorts with one hand without taking the other off the frying pan or plate or whatever it was. He would whistle or sing slowly, and Brian heard the tune as though it was coming directly from those knees, bending every now and again, hinting at the thighs beyond, which he wouldn’t see until later. But Brian would always touch them through Eugenio’s shorts without even getting up from the sofa they had in the kitchen. With just his nails or his fingertips, he’d trace the edges of his boxer shorts until he was told to stop. But that didn’t always happen, and sometimes the tap would be left running or the water would evaporate on the hob. When they’d finished fucking, Brian would become quite the chatterbox, and Eugenio would half listen from the kitchen, in his dressing gown. READ MORE…

Graphic Novel in Translation: Karim Zaimović’s “The Invisible Man from Sarajevo”

Translating genre, language, text, and image—this is Asymptote blog's first graphic novel in translation