Diaz’s Forest

Translated by Susan Bernofsky

In a forest painted by Diaz, a little motherkin and her child stood still. They were now a good hour from the village. Gnarled trunks spoke a primeval tongue. The mother said to her child: “In my opinion, you shouldn’t cling to my apron strings like that. As if I were here only for you. Benighted creature, what could you be thinking? You’re just a small child, yet want to make grownups dependent on you. How ill-considered. A certain amount of thinking must enter your slumbering head, and to make that happen, I shall now leave you here, alone. Stop clutching at me with those little hands this instant, you uncouth, importunate thing! I have every reason to be angry with you—and I believe I am. It’s time you were told the unadorned truth, otherwise you’ll stay a helpless child all your life, forever reliant on your mother. To teach you what it means to love me, you must be left to your own resources, you’ll have to seek out strangers and serve them, hearing nothing but harsh words from them for a year, two years, perhaps longer. Then you’ll know what I was to you. But always at your side, I am unknown to you. That’s right, child, you make no effort at all, you don’t even know what effort is, let alone tenderness, you uncompassionate creature. Always having me at your side makes you mentally indolent. Not for a minute do you stop to think—that’s what indolence is. You must go to work, my child, you’ll manage it if you want to—and you’ll have no choice but to want to. I swear to you, as truthfully as I am standing here with you in this forest painted by Diaz, you must earn your livelihood with bitter toil so that you will not go to ruin inwardly. Many children grow coarse when they are coddled, because they never learn to be thoughtful, thankful. Later, they all turn into ladies and gentlemen who are beautiful and elegant on the outside but self-absorbed nonetheless. To save you from becoming cruel and succumbing to foolishnesses, I am treating you roughly, because overly solicitous treatment produces people free from conscience and care.”

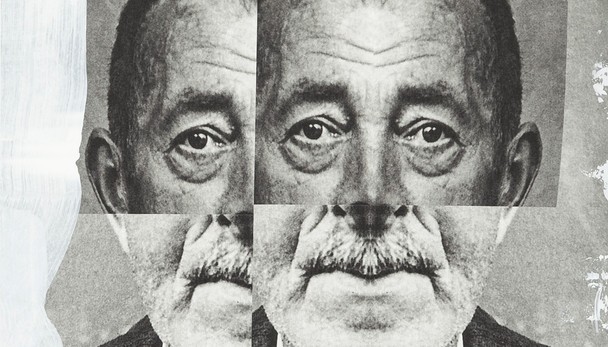

Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, The Forest Clearing, 1875. Photo: Private Collection.

As the child heard these words, it opened its eyes wide in terror, trembling, and a tremor passed through the very leaves of Diaz’s forest, but the mighty trunks stood firm.

The fallen leaves upon the forest floor murmured: “What has been written in this brief essay appears to be quite simple, but there are times when everything simple and readily comprehensible recedes from human understanding and only can be grasped with great effort.” That’s what the leaves murmured. The mother was gone. The child stood there alone. Before this child stood the task of finding its way in the world, which is also a forest, of learning to hold itself in low esteem and to drive out all smug complacency from its own person, so that it might be pleasing to others.

***

Beardsley

Translated by Lydia Davis

Have you ever seen drawings by this Englishman, whom one can only imagine young? I have no doubt that he always went about very elegantly dressed. About the facts of his life I really know only this, that he moved to Paris, evidently because a kind of longing drew him to the city. He rented a large, nicely decorated room for himself. Of course it could also have been two, or even three, rooms. Here, he read many books and also drew, or maybe he drew first and foremost, and reading came only second, third, or even fourth. I remember having seen a wonderful drawing he did of a pair of scissors. When drawing perhaps tired him a little, he would reach for his pen, in order to write. I read a very small book of prose by him that struck me as an enchanting thing, i.e., that seemed to me very capriciously and stylishly composed, I mean written. Now and then he also wrote poetry. Above all, however, he drew like the springtime, so tender, dreamy. Yet the most excellent thing about it was this: he was not lacking in solidity, a solidity endowed with something celebratory, nor in precision, a precision that expressed something pleasing. If I am imagining him accurately, he would often lie all day with a graceful and very exact indolence in his luxuriously outfitted bed. His periods of indolence were perhaps a kind of work. Such was the appearance of his drawn images that people believed these pieces of embroidery, as they liked to call his works of art, had been created by warbling, tunefully dabbling chaffinches and robins. Did he make a name for himself as an illustrator? Certainly. Did he often go to the theater? I think so. Did he die young? So it seems. Among other pages, there exists one by him depicting a burning candle. It may be that never before has an illustrator reproduced the flickering of a candle in so candle-like a manner, so flickery. He drew women with unspeakably alluring lips and unspeakably delicate little noses, and he drew the styling of women’s hair, and with his drawing pencil he led us into the most bewildering, vegetation-rich gardens. When he felt his earthly end approaching, it irritated him somewhat that he had evidently produced, alas, almost a little too much. He had little or no cause for this. He felt, quite simply, merely weak, illness makes us somewhat too compliant in our relations with society, with our fellow creatures. Perhaps he was enamored of the apologetic demeanor, since he was truly very sensitive.

Aubrey Beardsley, Self-Portrait, c. 1892. British Museum, London. Photo: akg-images.

It is possible that he dared show us eyes that bore witness all too eloquently to worldly pleasures, this and several other things were now regretted by the Good Man with a sincerity embarrassing to those who smiled as they glanced at the sheets of paper, on account of which he pined away, something he would have been spared had he been by nature insensitive.

Today he seems to have been somewhat forgotten.

Well, then these lines will recall him.

It is pleasant to talk about someone who does not form the conversation of the day.

In doing so, one can appear to oneself quite refined.

*****

Born in Switzerland in 1878, Robert Walser worked as a bank clerk, a butler in a castle, and an inventor’s assistant while beginning what was to become a prodigious literary career. Between 1899 and his forced hospitalization in 1933 with a now much-disputed diagnosis of schizophrenia, Walser produced as many as seven novels and more than a thousand short stories and prose pieces. Though he enjoyed limited popular success during his lifetime, his contemporary admirers included Franz Kafka, Hermann Hesse, Robert Musil, and Walter Benjamin. Today he is acknowledged as one of the most important and original literary voices of the twentieth century.

Susan Bernofsky directs the literary translation program in the School of the Arts MFA Program in Writing at Columbia University. She has translated over twenty books, including seven by the great Swiss-German modernist author Robert Walser, Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, Hesse’s Siddhartha and, most recently, The End of Days by Jenny Erpenbeck. Her many prizes and awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship this year, as well as the Helen and Kurt Wolff Translation Prize and the Hermann Hesse Translation Prize. She blogs about translation at www.translationista.net.

Lydia Davis was awarded the 2003 French-American Foundation Translation Prize for her translation of Marcel Proust’s Swann’s Way and was named a Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French Government for her fiction and her translations of such modern writers as Maurice Blanchot and Michel Leiris. She is the author of one novel, The End of the Story, and several volumes of stories, including Varieties of Disturbance, a National Book Award Finalist, and Can’t and Won’t, a New York Times bestseller. In 2009 her stories were brought together in one volume, The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis, which was called “a grand cumulative achievement” and “one of the great, strange American literary contributions” by James Wood in The New Yorker and “one of the great books in recent literature” by Dan Chiasson in the New York Review of Books. A MacArthur Fellow, Davis lives near Albany, New York.

These excerpts from Looking at Pictures are published by permissions of Christine Burgin and New Directions Publishing. Copyright © Suhrkamp Verlag Zurich 1985. License edition by permission of the owner of rights, Carl-Seelig-Stiftung, Zurich. “Diaz’s Forest” translation copyright © 2015 by Susan Bernofsky. “Beardsley” translation copyright © 2015 by Lydia Davis.