In Wilma Stockenström’s novel, Expedition to the Baobab Tree, we meet a woman who has no language of her own. Captured as a young girl and sold into slavery, she can identify neither with the fractured “worker’s language” of her fellow slaves nor the Afrikaans imposed on her by her owners, instead becoming alienated from both groups. Since the languages we speak provide us with internalized values and systems of categorization to understand and locate ourselves within the world, Stockenström’s protagonist’s lack leaves her disoriented and struggling to construct an identity. She discards the constraints of human language, culture, and systems of categorization; unraveling her conditioning as a slave, she improvises a language of her own, a vocabulary masterfully crafted in Stockenström’s prose and expertly preserved in Coetzee’s translation. Yet having internalized her worth as determined by her usefulness to her masters, she finds her solitude in the wilderness unbearable, the maddening isolation finally driving her to suicide. READ MORE…

Essays

There’s a great deal of music in American Hustle (originally and more appropriately called American Bullshit), no surprise for a period picture that takes great care with the costumes and especially the curls of its con-men characters. What is surprising is that a great deal of the admittedly great music chosen is a little rote, either in terms of sonic 70s shorthand (Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” stands for disco and drugs) or through blunt lyrical parallels (Santana’s “Evil Ways” or Steely Dan’s “Dirty Work”). It’s not all that obvious, though, as on-set improvisation led director David O. Russell and Jennifer Lawrence to take Wings’ “Live and Let Die” and turn McCartney’s Bond tune into a villainous call to arms for Lawrence’s dangerously unbalanced character.

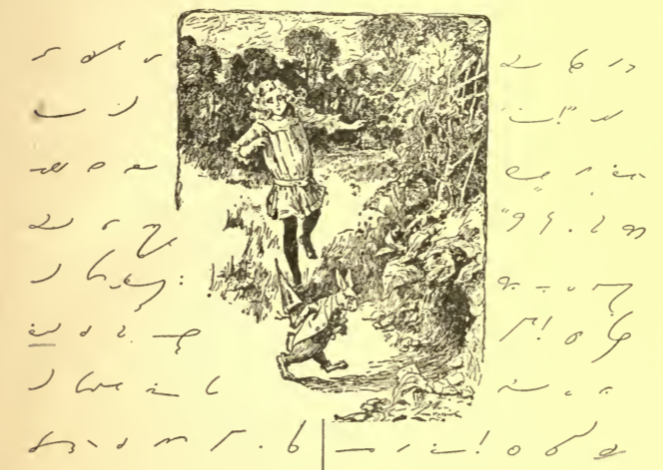

I don’t claim to be an expert on Pushkin’s poetry, in fact I might say there’s only one work of his I’m thoroughly acquainted with, and that’s Eugene Onegin. I‘ve read his lyrical and epic poetry, his fiction, drama and correspondence, of course, and have read up on the poet and his work, yet Eugene Onegin holds quite an exceptional place in my reading and perception of Pushkin.

I did not like 2013 and I’m not sorry to see it go. It’s taking with it some dear loves and some beloved stars, and so I’ll live with it my whole life. When tomorrow comes, this will be a year ago.

A couple of weeks ago I was looking for a book at home and my eyes kept being drawn to big books: 2666, The Emperor of Lies, Ulysses, The Satanic Verses, Stone Upon Stone. Thick books with titles and author names in large font—and I noticed all by men. And what about women? I’d studied literature, helped judge the Best Translated Book Award a couple times, and I review books, so I assumed I had lots of big books, a good balance of literary work by everyone from everywhere. In a few minutes’ time though I counted eighteen big, 500-plus-page books by men and just one by a woman: Simone De Beauvoir’s The Second Sex.

I’ve been working on an art exhibition called LOST HORIZON this year which has meant re-visiting the James Hilton classic from 1932 — ‘The first paperback ever published’ —or so the blurbs say. This is where the term ‘Shangri-La’ comes from. The movie, by Frank Capra is wonderful, too.

Jan Henrik Swahn was born in 1959 in Lund. He grew up in Copenhagen and from 1970 on has lived in Malmö. His first novel, I Can Stop a Sea, about life in two gangster’s houses in a poor village in Normandie, was published in 1986 by Bonniers, the biggest publishing house in Sweden. The ten novels that followed were all published by Bonniers, and he was chief editor of Bonniers Literary Magazine from 1997-1999.

Although I look forward to reading the “Best of the Year” posts from my fellow readers, I hesitated to write one myself. My reading rarely aligns with the year’s releases, and if I could I’d positively enjoin everyone from reading primarily contemporary writing. The past, too, is a foreign country, and, in the transnational spirit of Asymptote, it’s another country that we ought to make a habit of visiting.

READ MORE…

Jaan Kaplinski was born to an Estonian mother and Polish father in 1941 in Tartu, Estonia. His father was arrested by the NKVD for ‘possible subversive anti-Soviet activity’ and disappeared in the Gulag archipelago during the war, probably dying in 1943. Says Kaplinski: “He saw me, but I have no memory of having seen him.”

Since I began publishing translations in Slovakia in 2011, I am often asked the same question: Why start a publishing house when there are so many different options and people are so distracted by new technologies that they do not have time to read anyway?

When Beckett translated his own En Attendant Godot into Waiting for Godot it was an act of editing as much as anything else. Some of his changes were quite normal for a translator (the selection of the best words, the retention of the play’s themes and shape and humor) and some unique to the self-translator: reworking passages, adding phrases (a whole back-and-forth of cursing, for instance), cutting speeches. The French is riddled with rien; the English with ‘nothing.’ In one of his many amusing alterations he turns phoque (the French word for seal, which sounds like the English cuss ‘fuck’) into ‘grampus,’ which is an obscure English word for dolphin that sounds, if pronounced like a Frenchman, like a small turd. READ MORE…

In pop music, much as in fashion, revivals are marked by a unique mixture of ignorance and nostalgia. The sounds and songs of yesterday are only successfully revived when audiences are divided about 50/50 between people who lived through the original era and kids to whom it all sounds fresh and new (if comfortingly familiar somehow). This means that musical genres can be dusted off every 25 years or so—say, when anniversary editions or write-ups appear, or when new artists emerge who’ve immersed themselves in records that are at that point ‘forgotten’ or even derided. 2013, for instance, has seen a newfound interest in two genres that have been mostly dormant since their critical and popular 90s heyday: trip hop, a Bristol-born musical genre clubbed to death by overexposure in coffee shops and boutiques, and (for lack of a better term) ‘indie rock’, and by that I mean the mildly dissonant, charmingly ramshackle, and highly dynamic guitar-based variety as made popular by bands like Pavement and the Breeders, not the more produced and community-oriented music of Death Cab or Arcade Fire. READ MORE…

Several weeks ago, I was at a roundtable discussion on editing poetry translations for literary magazines1 at which the question of presenting translations along with their originals resulted in such a range of responses I’ve been unable to let the question go. Unsurprisingly, it was harder for the editors of print journals to accommodate two texts, even if they wanted to: both space and funds are at stake. On the other hand, Don Share, editor of Poetry Magazine, argued that publishing just the translation honors the translator’s work and grants the translation its independence. Erica Mena of Anomalous Press had a different—and to me, fascinating—approach to managing a translation’s independence: not wanting to encourage “reading across the gutter,” the online journal she edits (which you should absolutely visit) publishes the source text in a pop-up window, not en face. “Reading across the gutter,” as I understand it, refers to the sort of reading in which a person compares original and translation word-for-word and line-by-line, checking for “mistakes”—in other words, the sort of reading an en face presentation could unintentionally promote.

Reading often fools us into feeling like we’re conversing—the words touch our eyes and yet seem to come in through our ears. It is no wonder that people often feel a bond to their favorite writers, their favorite books. They think of them as friends—that first person voice is talking to me, this story was crafted with me in mind. We extract secret meanings: my definition of blue is not the same as yours (I think of a butterfly my mother captured when I was in elementary school); I render Middle Earth far differently than Peter Jackson. Every book is a Choose Your Own Adventure, that way.