Jaan Kaplinski was born to an Estonian mother and Polish father in 1941 in Tartu, Estonia. His father was arrested by the NKVD for ‘possible subversive anti-Soviet activity’ and disappeared in the Gulag archipelago during the war, probably dying in 1943. Says Kaplinski: “He saw me, but I have no memory of having seen him.”

Kaplinski says he ‘caught’ English by being an inveterate listener to the BBC, and he studied linguistics at Tartu University. He discovered the magic of poetry by reading Lermontov, which was to him like a religious awakening, at the age of thirteen. “This remains deep inside, an enormous influence,” he tells me. “I was writing short stories and essays, it was not easy to be published. It was a bit easier to be a poet.”

He has worked as a researcher in linguistics; as a sociologist; an ecologist; and as a translator from several languages into Estonian. He is a member of many learned societies and the Universal Academy of Cultures headed by Elie Wiesel. He has lectured on the history of Western civilization at Tartu University. During the Perestroika and Estonian national revival he was active as a journalist both at home and abroad and for a time a he wrote for a Finnish newspaper.

“Suddenly world politics came home – it was possible to write. Other countries were interested.”

When Kaplinski was elected to the Parliament he was at first unenthusiastic, though he gradually warmed to it. “When Estonia gained independence we had no politicians, only people with ideas. For a legislature to operate there is a need to know jurisprudence, economics, diplomacy – we did not know any of these things.” The new Parliament made one hundred laws in six months, laws about property and the like that Kaplinski had little experience with; a colleague from another country said they had struggled with two laws for the entire half year. Yet “because we were naïve, we succeeded,” Kaplinski says, and from 1992 – 1995 he was deputy of the Estonian Parliament (Riigikogu).

During this time Kaplinski lived in a hotel in Tallinn, returning exhausted in the evenings, watching Finnish detective films to relax, and translating classical Chinese poetry into Estonian. “China is like a great museum in which everything is preserved,” he says. He reads from the original, focusing on Su Dong Po (Su Shi) from the Sung dynasty. This has had an immediately apparent impact on his own writing and one of his poetry collections published in the 90s includes translations. Kaplinski has published several books of poetry and essays in Estonian, Finnish and English, and has been translated into Norwegian, Swedish, Latvian, Russian and Czech. He has also translated—mostly poetry—from French, English, Spanish, Chinese and Swedish. Perhaps most notable of these is the work of the 2011 Nobel laureate Tomas Tranströmer, who Kaplinski championed for the 1990 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

Far-off lands and foreign peoples are a dream,

a dreaming with open eyes

somebody does not wake from.

Kaplinski is fascinated by ancient languages, particularly the southeastern Estonian language, Võru Keel, which has been assimilated as a dialect. “I want to write in this language, it should be my own,” he says. “My genes are from southeast Estonia, old Livonia, our capital was Riga.” He tells me the different ways to say ‘Don’t be afraid’: Northeastern Estonia would say ‘ära karda’; in the South, ‘peläku i’’. Such sounds are common in Semitic languages, in ancient Hebrew, perhaps similar to Latgalian, he says.

He has also written fiction in addition to his many works of translation and poetry, a novel called The Same River. “A novel cannot be wholly autobiographical,” he says. “Of course some persons have prototypes. Life is not so easy to describe according to rules of literature – it needs to be transformed. Life can imitate literature – nowadays replaced by cinema.

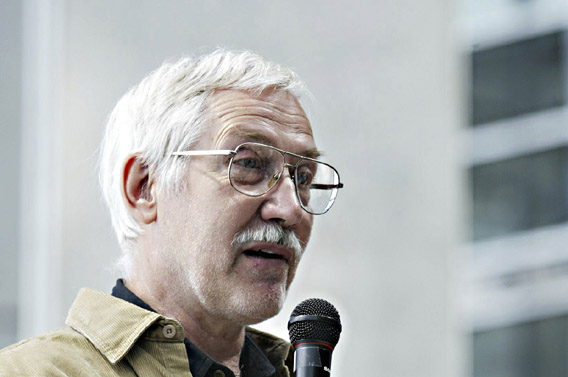

“The way we see our life, how we live and don’t want to live, then maybe we see it as literature,” he says. “The influence of language—literary patterns—are used in our thinking.” Kaplinski notes that the Confucian system has survived longer than any other. He absorbs like a sponge; at 72 he remains a vibrant, lively man.

He thinks that The Same River will be published in Ethiopia, in Amharic, and hopes that if the Estonia Cultural Capital Fund provides the funding for publication, he can go to Addis Ababa as a guest. His eyes light up: this is what he wants more than anything, to go to Addis Ababa.

Kaplinski is now writing poetry in Russian; I ask him whether there will be another novel. He says: “I am not so happy with writing and writing, there is a terrible semiotic inflation, too much – monetary inflation is a special case – more and more books, poems, each means less and less.”

He says it was different in Soviet times, because there was far less written work available, and the few books in stores sold well and were discussed. Sensitive topics were touched upon in drama, songs.

I ask about corruption, and he replies that Estonia, like Latvia, is a small country where everyone knows each other and is connected. “I don’t think the building of that mall, for instance,” he says, pointing, “Could be said to be absolutely ‘clean.’ But it’s not a big problem.”

I tell him that I’ve heard his name mentioned as a possible candidate for the Nobel Prize and ask him how he feels. “It would be good because it will help me support my family,” he says. He survives on his pension as a former deputy. He cannot support himself simply as a writer. Unlike the Culture Capital Foundation in Latvia, the Estonian Cultural Capital Fund does not give lifetime grants to writers and artists. “My daughter is a poet, and a single parent,” he says. “I don’t know how she manages.”

Yet it’s clear that in his life he has found happiness and interests, weaving thoughts and perceptions into his poetry, always delving deeper into what there is. As in his poem about a delivery of Silesian coal:

I’m happy to have it and – as always – I regret a little

that I must burn something so wonderful

without having time to study it, to open layer by layer

the book that has been buried and hidden so long . . .

Always a book, a black book in a foreign language

from which I understand only some single words:

Cordaites, Bennetites, Sigullaria . . .

—

Inara Cedrins is an artist, writer, and translator from Latvian to English.