I did not like 2013 and I’m not sorry to see it go. It’s taking with it some dear loves and some beloved stars, and so I’ll live with it my whole life. When tomorrow comes, this will be a year ago.

We resolve to be better when December becomes January. We say: I will quit smoking I will go back to school I will lose five pounds. We throw parties to mark a change the sun marks by appearing a smidgen earlier or later depending on where you live; we carouse late into the night as if 2014 means anything besides now. In The Magic Mountain, Mann writes of this recurring moment: “Time has no divisions to mark its passage, there is never a thunderstorm or blare of trumpets to announce the beginning of a new month or year. Even when a new century begins it is only we mortals who ring bells and fire off pistols.” And of course he is right, and was right in 1924, but we mark up time with a bit of noise because to stay silent means to give in to going quietly. Every twelve months, we cheer for life.

So we make plans and share them, encourage each other, stoke each other’s fire. Some of these resolutions are deviations, attempts to reinvent the self the way the year so easily can. I suppose for writers deviations can be useful. How alluring it sounds to try a different form; to cast aside stifling sonnets for free verse, to date the blank page and leave the hundreds that have been giving so much heartache, to go along with something unburdened by past failures.

I’m sure there are things I will resolve to change and when the last moments of December stumble in I’ll think of them, but I’m looking at fourteen as a year to keep on. For the past few months I’ve been reading Anna Karenina. I’m doing this because I’ve never read it, firstly, and because I was sitting next to a very famous writer at a dinner one night, after an evening designed to honor her, and she turned to me and asked if I’d read Anna—she called it Anna—and I said the first thing that came to my lips from a mind that had been trying to figure out a way to engage her, and that thing was ‘yes.’ So we talked about it, her more than I, and I fidgeted and fumbled my way through the conversation until some phrase of hers bobbed long enough for me to cling to it, and, made buoyant again, I got us off Tolstoy.

I’m knee deep in it now, which means there are several hundred pages to go, and at the rate I’ve been reading it’ll be summer before I can be honest about Anna. Where I live it will be hot, probably the hottest ever or coming close, and I’ll be sweating on a park bench or in a too small apartment and the sky will be spotless and I’ll still be reading about Vronsky, unless he’s dead (I actually don’t know what happens, which seems sort of amazing).

And I’ll be writing and hopefully I’ll be writing the thing that I abandoned for too long in 2013 because I resolved in June that I needed to change. Tolstoy has this lovely line about Anna, early on before we know a thing about her besides how gorgeous she is. She’s at a party, she stands out even in a crowd of beauties, and something charms our heroine and her cheeks run red: Anna was capable of blushing. That’s the line. I love capable, how it’s a surprise. It’s a surprise to Kitty, who’s been watching from across the room, and to the reader, who now has to think about what kind of woman would appear to never need to blush but who suddenly has, and, I think, it’s a surprise to Anna. That she’s been able to all this time but hasn’t, so we know she’s been singularly moved. There are something like seven hundred pages left, but if it ended then it would still be a success, because there’s nothing better than that: to be going along, making your appearances, when life suddenly shakes you and says, I’m here.

—

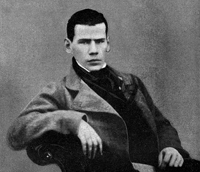

Above photo of Tolstoy at roughly the age of the author, Wikimedia Commons