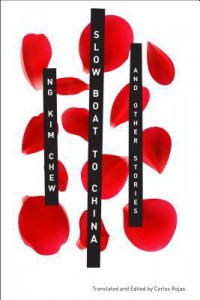

As far as anyone knows, in 1945 the Chinese poet and author Yu Dafu was executed by the Japanese military police, for whom he had secretly been acting as an interpreter during the War of Japanese Resistance. As translator Carlos Rojas explains it, one evening “a visitor came to Yu’s home [in Sumatra] and asked him to step outside, and he was never seen again.”

Half a century later, Malaysian author and professor of Chinese literature Ng Kim Chew is obsessed with the possibilities. What if Yu survived? He was a polyglot, he had all the promise of an amazing writer—he could have been the Great Author that China was searching for. What if he escaped the Japanese and went on with life elsewhere? In Slow Boat to China and Other Stories, we see an array of vastly different realities.

Now, not all the stories in Ng’s collection concern the possible fates of Yu Dafu, although they represent a sizeable portion. Slow Boat to China leads off with “The Disappearance of M,” which chronicles the public frenzy—and personal obsession for our protagonist—of trying to determine the identity of the author behind the critically acclaimed novel Kristmas, which is written in what amounts to a completely new language; its base is English, but it includes Arabic, German, Javanese, and Chinese oracle bone script among many other languages.

In searching for the identity of the anonymous author, all the world has to go on is the letter “M,” a West Malaysian postmark and a charge to a Chinese deposit company. Native Malaysian writers and Malaysian writers of Chinese descent both claim the author for themselves, but no one is really sure. With the sophisticated linguistic background required to craft such a work, they must be a very special person indeed. Questions arise about the legitimacy of claiming the work for any one national heritage: can something written in English really be considered to be a great work of Chinese or Malaysian literature? A Chinese writer’s group decides that the real task is to find the original Chinese version of the work, which must exist, and work from there.

It’s hard not to be reminded of the furor in the literary community which gets stirred up every now and then when someone engages in amateur detective work and points the Finger of Ferrante at an unsuspecting colleague or mild-mannered professor of Italian literature. A scene at a “National Literature Discussion Panel” is especially amusing in this regard, with authors analyzing Kristmas and positing others present as possible “M”’s only to come across new evidence and whip the compliment out from under their fellows a second later. The protagonist of the piece, a reporter, has his own suspicions, and follows a trail back to the possibility that Yu Dafu lives on and is fulfilling his literary destiny from the anonymity of the Malaysian rubber forests. (Reporters, it’s worth noting, are particularly intrigued with the whereabouts of Yu Dafu in Ng’s writing.)

The concern with Yu Dafu and his possible relocation to Malaysia speaks to something beyond a personal obsession with a probably long-deceased author. The Malaysian identity—and specifically the identity of the Chinese Malaysian—is at the forefront in much of the work here. “A Chinese. . . But what is a Chinese?” the narrator of “Allah’s Will” asks. If Yu Dafu fled to Malaysia and settled down, would he be a Chinese author or a Malaysian author? In “Allah’s Will,” the narrator thinks:

“For thirty years I haven’t spoken Chinese, haven’t written Chinese, and haven’t read Chinese. Instead, I have spoken Malay, taught Malay, have abstained from pork… Yet that Chinese flame in my heart hasn’t been extinguished. I often wondered why couldn’t I become completely Malay, given that I was no longer able to be completely Chinese? Was it because of the unerasable past?”

“The unerasable past” wouldn’t be a half-bad alternate title for this collection. Everyone is haunted by their past, whether the past is the past where Yu Dafu disappeared, the past where they left their homes for a new country and new opportunity, or the past where they lost someone or part of themselves. Heritage and history, especially the melding of different cultures and ethnicities and all the creativity and conflict that this can cause—look no further than the debate over “M”’s identity for evidence—are at the forefront in every piece here.

It is less the themes and more the character of the writing in this collection that really drew me in, however. Ng’s experimental writing traipses on the borders of reality, as though everything that happens is distorted by the swampy, thick air of the forest where much of his action takes place. Dream is indistinguishable from fact until the last second, woven into the narrative seamlessly only to set both reader and character up for an abrupt drop into reality. Dream and Swine and Aurora implements this in a way which is genuinely, stiflingly terrifying: a seemingly infinite Russian dolls of a dream of waking, each layer slightly more surreal than the last. Memory and conscious thought get tangled up all the time, and keeping track of reality sometimes feels like trying to breathe under water. It’s hard to read, but it’s rewarding. This is definitely not a one-sitting kind of collection. You will need some time to recover.

As a whole, the collection is nicely curated and all the stories fit together in a sensible way. Carlos Rojas, Chinese translator extraordinaire, doesn’t disappoint in his masterful rendering of Ng’s tricky prose. The only piece I felt was slightly disjointed was the first story, the aforementioned “The Disappearance of M,” which seemed to me a little choppy and awkward. Given the linguistic complexity of Ng’s writing, however, this is the smallest of foibles. Rojas’s introduction is an invaluable part of this collection, both setting up the cultural context for Ng’s work, and explaining some of the linguistic trickery that needed to be accounted for in translation. As an English introduction to a great Malaysian author, I could hardly ask for better.