Mačka/macska (cat); cukor/cukor (sugar) pálenka/pálinka (fruit brandy); kabát/kabát(coat); taška/táska (bag); palacinka/palacsinta (pancake); bosorka/boszorkány (witch). These are just a few of the words that sound the same in Slovak and Hungarian. The surprisingly long glossary formed a witty and poignant visual backdrop to the main stand at this year’s Budapest International Book Festival, held 22-24 April, which had a focus on Slovak literature.

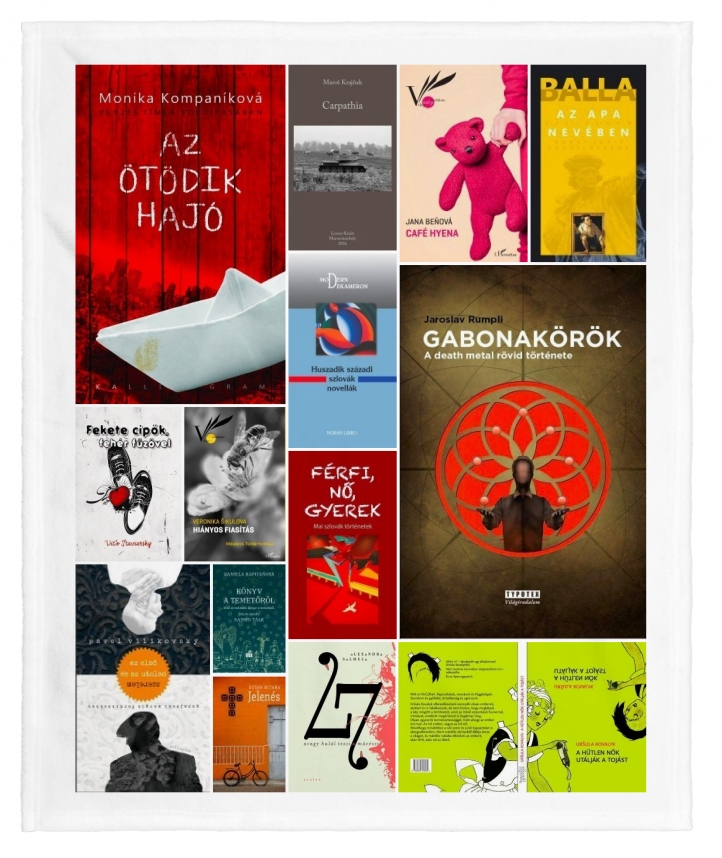

What did this mean in practice? Quite a lot: an audience of potential new readers in a neighbouring country; forty books by Slovak writers translated into Hungarian specially for this occasion; debates, book presentations, readings, discussions with authors, translators, publishers, journalists, scholars, historians—plus concerts, media interviews and interactive events for children. All that followed by receptions, informal conversations, fun.

Never has Slovak literature been presented abroad on such a massive scale. Never before have so many Slovak books been translated into any other language. And it is unlikely that such an event will happen again anytime soon.

The Budapest Book Festival is a major European literary event, with over 60,000 visitors every year. In the past guests have included such stars of the literary firmament as Umberto Eco and Paolo Coelho. This year it must have seen the greatest concentration of Slovak writers per square metre.

On the Slovak stand one presentation followed on the heels of the next from morning to night. All these Slovak books in Hungarian translation could easily be taken for granted without realizing the number of people who made this happen and the number of things—apart from money and institutional support—that had to come together for each and every book to land on the discussion table and arouse the interest it well deserved.

The book festival was preceded by “stock markets” held months earlier where Slovak publishers proposed books to their Hungarians colleagues, meetings where they tried to find a common language, a convergence of literary tastes and opinions on what constitutes literary quality. In parallel, translators held regular meetings to agree on titles and cooperate on the texts. Their hard work was appropriately acknowledged and celebrated.

Apart from everything else the book festival was an opportunity to present Hungarian-Slovak relations on a political level, something can be quite tricky particularly when these relations haven’t been exactly thriving or have been of a rather pragmatic nature. The fact that the Slovak minister of culture Marek Maďarič and his Hungarian counterpart Zoltán Balogh chose to pat each other on the back right at the Slovak stand made many of the Slovak authors uncomfortable. Because of the the highly centralised cultural policy pursued by their government Hungarian authors reacted even more strongly, refusing to support this particular event and thus legitimise their government. Their social and professional encounters with their Slovak colleagues were all the more cordial, very much in the spirit of the festival motto “Good Books Make Good Neighbours”. Had that not been the case one the greatest literary Europeans, Péter Esterházy, would hardly have been spotted at most of the Slovak events, despite being gravely ill.

“We need to show the politicians that good neighbourly relations are possible here, on the Eastern borders of the EU, which they are intent on marginalising by their eurosceptic activities. Our meeting is evidence of mutual respect, curiosity and a burning desire to get to know each other. Let’s show them that good neighbourly relations involve a different kind of Hungarian-Slovak cooperation from that practised by our current governments and their representatives, often amounting to little more than mutual distrust and an absence of openness,” said Hungarian writer Pál Závada in his address. He stressed that only by being simultaneously good patriots and good Europeans can we appreciate each other’s point of view and cast a critical eye over ourselves, recognising our own historical sins, moral failures and failings while maintaining good friendly relations.

Závada was happy to note that most of the forty Slovak books presented in Budapest were by women authors. “I’ve seen many national book catalogues but have never before seen anything like this,” he said of this highly unusual gender disparity.

It is the publication of these books in translation that gives genuine grounds for joy rather than the temporary elation that might be expected at a book fair. Slovak authors such as Pavel Vilikovský, Balla, Veronika Šikulová, Jana Beňová, Uršuľa Kovalyk, Monika Kompaníková, Daniela Kapitáňová, Zuska Kepplová, Mila Haugová, Alexandra Salmela, Peter Pišťanek, Jana Juráňová, Ondrej Štefánik, Víťo Staviarsky, Jaroslav Rumpli, Maroš Krajňak and many others have enriched the Hungarian book market with works that can no longer be ignored by the local literary community. The flood of reviews and media appearances is testimony that the crème de la crème of Hungarian writers have found the Slovak books inspiring, thought-provoking and stimulating. Slovak literature seems to have made its mark.

Clear proof, if any were needed, is provided by Balla’s short novel “In the Name of the Father”. Instead of hollow literary phrases, Hungarian writer Gábor Németh introduced the novella in style and had the audience, including Péter Esterházy, rolling in the aisles: “To read Balla is like returning to my childhood, when I invented a new sport, stream-crawling: you go along a stream, with the aim of jumping from rock to rock without getting your feet wet for as long as possible, relying on divine inspiration. You jump from sentence to sentence, trying to find one that will not give way, not letting you lose your balance entirely. Sooner or later you fall flat on your face.” (English readers will have an opportunity to experience this later this year when “In the Name of the Father” is published by Jantar Publishing in London, in a translation by Julia and Peter Sherwood.

Eva Andrejčáková

The author is an editor with the Slovak daily SME

*****

Read more Dispatches: