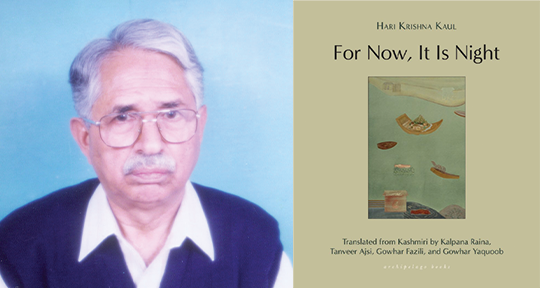

For Now, It Is Night by Hari Krishna Kaul, translated from the Kashmiri by Kalpana Raina, Tanveer Ajsi, Gowhar Fazili, and Gowhar Yaqoob, Archipelago Books, 2024

Hari Krishna Kaul (1934-2009) was a Kashmiri writer dedicated to inscribing the quotidian lives of people in the valley, releasing their stories in both fiction and dramatic works throughout his life. Some of these pieces have now been collected in For Now, It Is Night, which features seventeen stories picked from the four collections spanning Kaul’s career—two written and published before the watershed year of 1989, while the writer still lived in Kashmir; and two published after he and his family had migrated—just like many other Hindu families—in the Kashmiri Pandit exodus, which occurred upon the onset of militancy and rise in communal tensions after India’s Independence in 1947. As Kalpana Raina, Kaul’s niece and one of four translators in this volume, writes:

There are no grand themes in Kaul’s work, but an exploration and an acceptance of human limitations. He used his personal experiences to explore universal themes of isolation, individual and collective alienation, and the shifting circumstances of a community that went on to experience a significant loss of homeland, culture, and ultimately language.

One would assume that Kaul would become prejudiced after his exile, but that could not be farther from the truth. As Gowhar Fazili, another translator, states: “Unlike a partisan trend in contemporary Kashmiri writing—particularly in English—that victimises a community, demonising the other while valorising the self, Kaul subverts the binaries of good and evil, friend and enemy, self and other.” As exemplified in this selection, Kaul does not create reductive caricatures in the guise of characters, whether Muslim or Hindu. Moreover, neither the exodus, nor the events surrounding it, make up the sole focus of his narratives; he is not interested in the incidents themselves so much as the rootlessness and unbelonging they engendered. Tanveer Ajsi elaborates: “Not assuming the inclusive character of Kashmiri society, he excavated the strengths that bound it together, while also exposing the fault lines that lurked behind its cultural veneer.” As such, Kaul’s work can also be seen as a questioning of Kashmiriyat, the much-romanticised idea of communal harmony and religious syncretism in the Kashmir valley, which—despite its gradual erosion—still sees people swearing by its steadfastness.