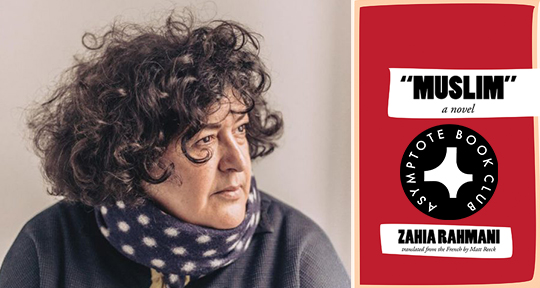

Zahia Rahmani’s “Muslim”: A Novel (translated into English by Matt Reeck and published by Deep Vellum) is a combination of fiction and essay, written with a “stark and uncompromising beauty.” When the novel was first excerpted in Asymptote back in 2015, Matt Reeck highlighted the way in which “The novel’s experimental form stages the gaps between places, and between accepted norms, where a person cast adrift must live.”

Now, Asymptote Book Club subscribers will have a chance to discover this “contemporary classic” in full. You can join our discussion on the Asymptote Book Club Facebook group, or sign up to receive next month’s title via our website.

“Muslim”: A Novel by Zahia Rahmani, translated from the French by Matt Reeck, Deep Vellum, 2019

Reviewed by Erik Noonan, Assistant Editor

The protagonist of Zahia Rahmani’s “Muslim”: A Novel has lived a life contained within the constraints of a pair of quotation marks. The exercise of her voice in the printed word—French in the original, English in a new translation by Matt Reeck—represents an effort to outtalk the multitude that would mischaracterize her and confine her to a type. She speaks out even though her efforts to liberate herself have only shrunk the bounds of her freedom.

Going first by the name of Rahman (Arabic, “the Merciful”) and later, while interned in a desert camp, Elohim (Hebrew, “God”), the main character, born in the Kabylia region of interwar Algeria in 1962 “in a society between times,” escapes with her family as “a child of Ishmael, the abandoned child, the child born of a castoff slave.” Her mother is Berber, her father a Harki, and existence has become impossible in their country where “in its fight, in its desire to construct cultural cohesion throughout its lands, pan-Arabism found that it had only one tool, Islam,” and where “it was necessary to extinguish the all too human light that remained in everyone else, the ‘survivors’ in that period between wars.” The family settles in Europe, “holed up in a little bit of the French countryside” in which the child strives to learn her mother’s language “from recordings borrowed from the deepest reaches of libraries.” She finds herself “no longer alone and abandoned” within this newfound maternal connection, but also finds—because she has a new identity in her isolation with her books, not “just an exile, an immigrant, an Arab, a Berber, a Muslim or a foreigner, but something more”—the French language has imposed a harsh consequence: “because of my straying, she threw me out.” Expelled by the French language for her disloyalty, Rahman-Elohim goes a step further and departs the French nation. “It’s for that reason, that act of treason, that I’m in this camp.” And here, amidst the sand that “reigns supreme over all military strategy and over every army,” she renders her account.

The prose of “Muslim”: A Novel is compact, dense, swift. It orients a self amid a kind of compound menace made up of forces coming at her from all sides, such that the theme of positionality emerges, and we read in her consciousness that the human spirit dwells in contradistinction to circumstance. Rahmani’s theme is evident in her treatment of the historical conditioning of sacred texts (“Whether out of affection or necessity, Muhammad liked to listen to the stories of the Jewish people, a community that modeled faithfulness to God, which he respected”), the duplicity of revolt (“The slogans offered a way forward, and our fathers went to the pharmaceutical factories, where they were encouraged to join the strikes and demonstrations. They began to fear for their lives again”), and the weaponization of culture (“All of Algeria was forced to become more Arab. Not just to speak Arabic, but to become Arab”).

So, in the closing pages, Rahman-Elohim reaches the final impasse of tension between herself and her surroundings, with the following lines about her fellow internees addressed to her anonymous captors: “I’m the one who’s scared. Not them. They don’t trust you. They don’t talk to you. You’re an abomination in their eyes. An abomination. Do you understand? Me, I’m scared. I don’t have their conviction.” The exactitude of the author’s art and the stark and uncompromising beauty of Zahia Rahmani’s prose combine to make “Muslim”: A Novel a contemporary classic.

Erik Noonan is from Los Angeles, California, USA. He is the author of the poetry collections Stances and Haiku d’Etat. For more, please visit eriknoonan.net.

*****

Read more about the Book Club on the Asymptote blog: