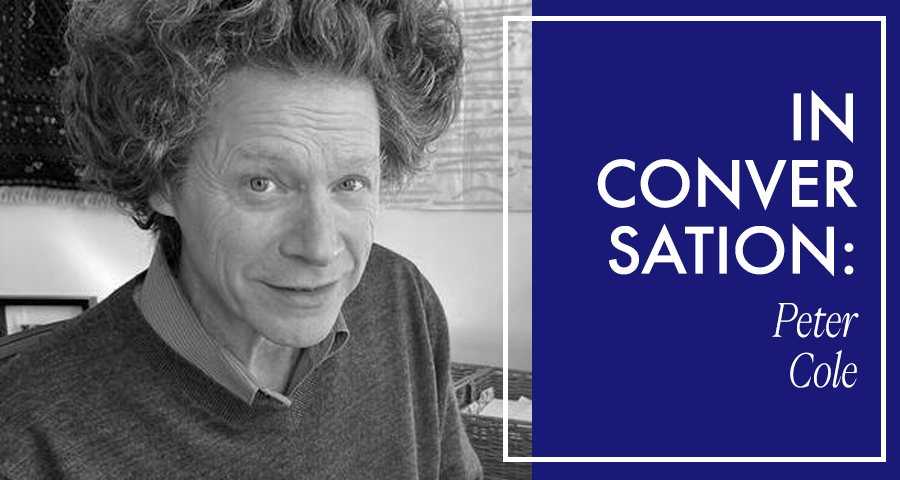

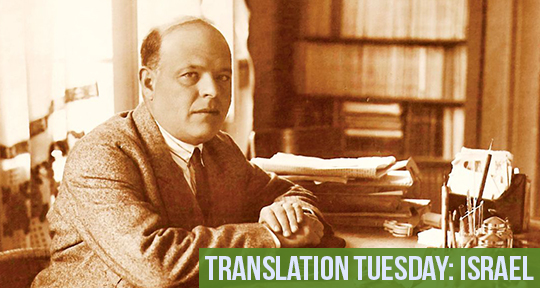

Peter Cole, a MacArthur Fellow and a Professor in the Practice at Yale, is a poet and a translator from Hebrew and Arabic. His past translation projects include the Hebrew poetry of Muslim and Christian Spain, the poetry of Kabbalah, and the works of the Palestinian poet Taha Muhammad Ali. In October, New York Review Books brought out On the Slaughter, Cole’s translated selection of poems by Hayim Nahman Bialik (1873-1934), the Ukrainian-born Jew who became not only the pre-eminent Hebrew poet of his time, but also the major cultural figure of both the Jewish diaspora and the nascent Jewish community in Ottoman and British Mandate Palestine. Bialik is still regarded as something of the patron saint of modern Hebrew literature.

Recently, I paid Cole a visit in New Haven. Walking along the harbor, sitting over tea and dried apricots at his table, and, later, conversing over email, we discussed the mists surrounding the complex and contested figure of Bialik; October 7 and its genocidal aftermath in Gaza; how translation fits into the matrix of history, poetry, and ideology; and more.

Daniel Yadin (DY): I’d imagine that many of our readers are hearing about Bialik for the first time, though he’s an institution in the Jewish world. Bialik is the poet of modern Hebrew—at least, the granddad of the bunch. In your introduction to On the Slaughter, you talk about the ways in which you present a counter-reading of the poet. I agree you’re reading against the grain here. Would you say you’re also translating against the grain?

Peter Cole (PC): At the most basic level I’d say I was actually translating with the grain of the poetry—and certainly its granularity, since translation as I know and love it entails the slippery business of trying to give an honest, if fabricated, account of one’s readings and what Blake calls their minute particulars. That’s “fabricated” as in constructed or woven, a made thing.

DY: Almost tactile.

PC: Almost and then some. I’m trying to bring a compound of literary and historical alertness to my encounter with these poems. At the same time, I’m also translating against the grain of the received version of Bialik, who—as you note—was a titan of Hebrew poetry in a public way that may be hard for Americans to wrap their minds around. Some 100,000 people attended his 1934 funeral in Tel Aviv—which is to say, half of the Jewish population of British Mandatory Palestine.