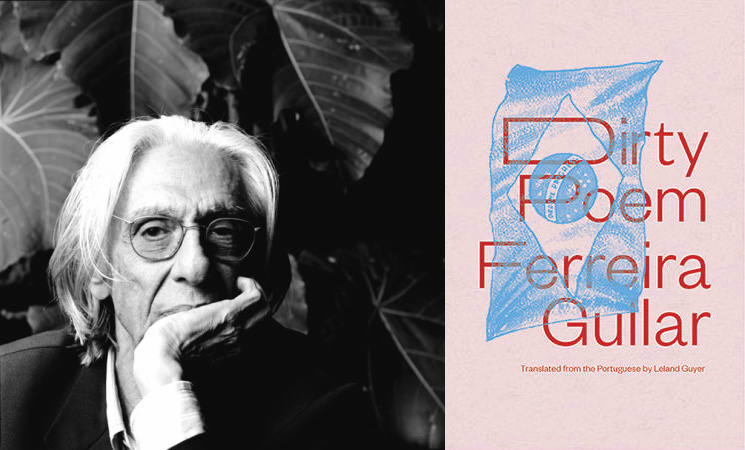

Much has already been said about exile. Losing a country or losing a home is “like death but without death’s ultimate mercy,” “a kind of ripping apart,” “a condition of terminal loss.” Ferreira Gullar wrote Dirty Poem (newly translated by Leland Guyer for New Directions) in 1975 in Buenos Aires, while in political exile from the Brazilian dictatorship. Like the author himself, the speaker of Dirty Poem imagines his return home, an attempt to recover the São Luís do Maranhão of his childhood.

The opening stanzas of this 80-page poem are filled with gaiety and fond memories of youth in the northeast region of Brazil. But just a few pages later, the speaker “preaches subversion of political order” and is banished to Argentina. In a fine translation from the Portuguese, Leland Guyer captures the richness of language of Gullar’s poetry—from local idioms to the language of displacement. The book culminates in saudade, alienation, and decay. READ MORE…