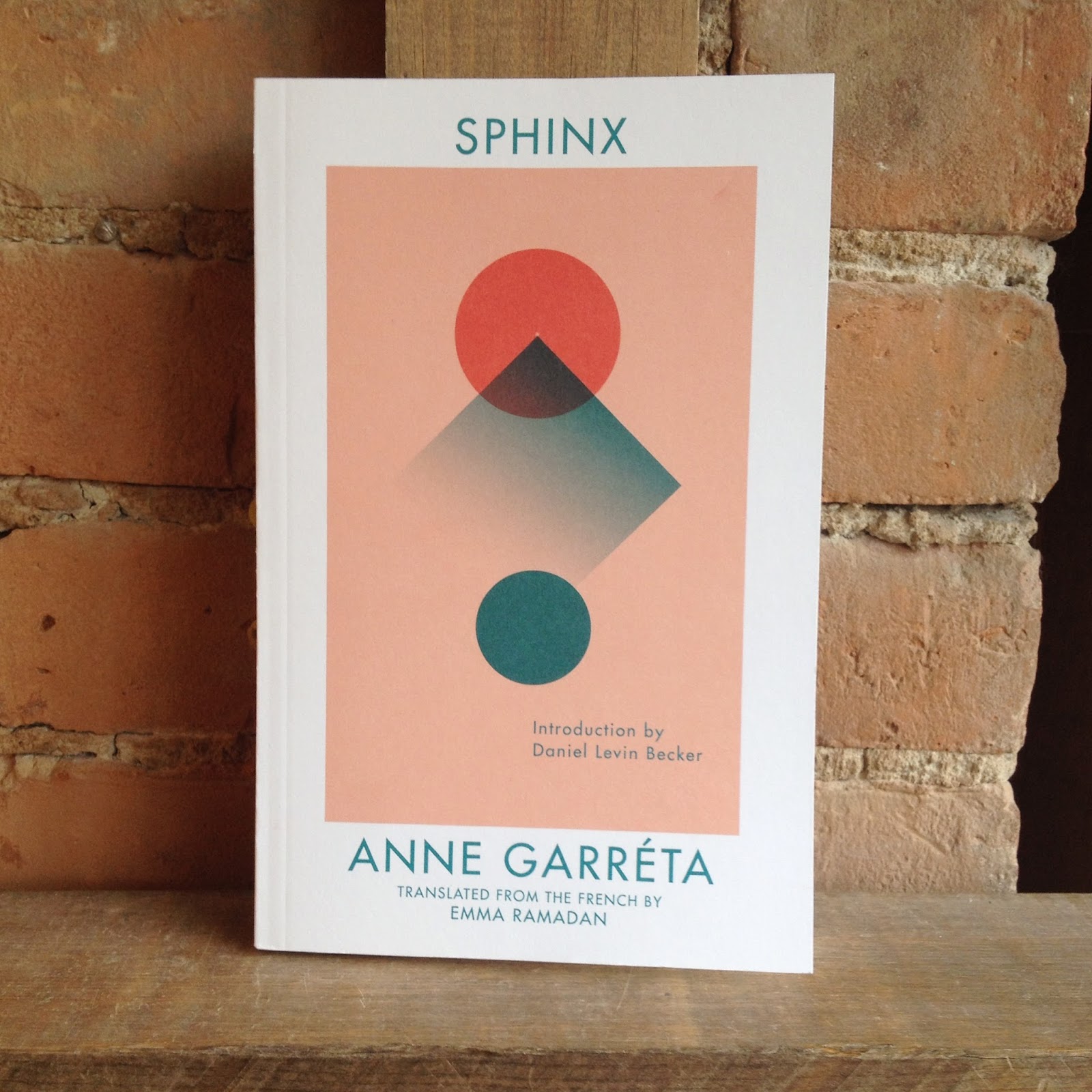

“If Garréta’s composition of Sphinx was a high-wire act, then Emma Ramadan’s task in carrying it over into a language with at least one crucially important constitutional difference is, near as I can figure it, akin to one tightrope walker mimicking the high-wire act of a second walker on a steeply diverging tightrope, while also doing a handstand.” —Daniel Levin Becker

If DJs are “the new rock stars” (Forbes, 2012), and if Emma Ramadan is correct—there did not exist, until now (2015), a genderless love story written in English—how can we trust in our vision as a supposedly contemporary, world-changing literary public after discovering that Anne Garréta’s debut novel was published thirty years ago?

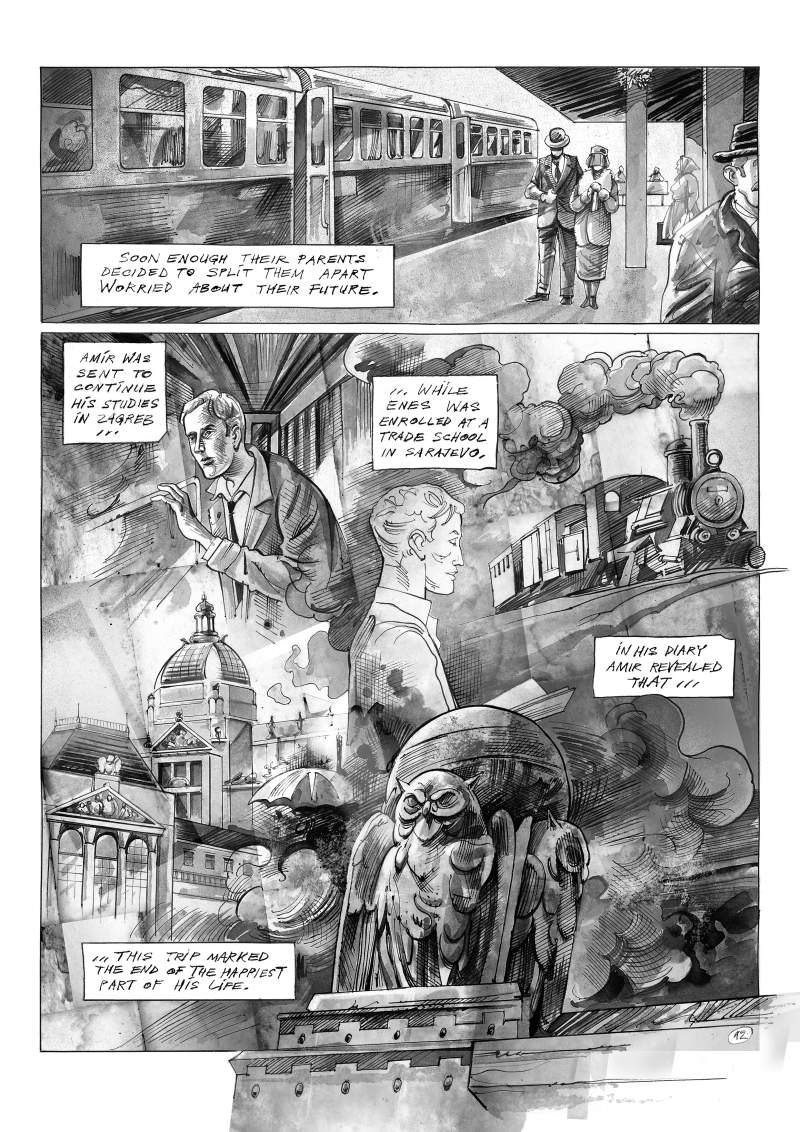

Sphinx (1986) is a love story that is simultaneously hijacked and elevated by its own language. Originally guided by a Jesuit priest cloaked as Dante’s Virgil, the novel’s nameless and genderless narrator descends from the aristocratic literati into Paris’s crepuscular underworld, arriving at the gates of the discothèque Apocryphe to become DJ royale and a devotee of the beautiful, also genderless, A*** (in whose tragic character we may find our Beatrice). The Apocryphe is the abyssal incubator of their folie à deux. To say that Sphinx is “ahead of its time” sounds stale, but stale-sounding things are often true. (In 2002, Garréta won France’s prestigious Prix Médicis, which is awarded each year to an author whose “fame does not yet match their talent.”)

Garréta’s method and style allow her to pillage the French language generously, often playfully, and she makes it clear that society, self-prescriptive by nature, is begging to see itself outside of binary gender distinctions. Ramadan’s translation has also given us the first full-length work by a female member of the Oulipo. The experimental French literary group is renowned for its exclusions—whole novels don’t include the letter “e,” extended texts employ only one vowel, poetry is written to be sliced up and reshuffled. It must be remembered, however, that Sphinx’s publication preceded Garréta’s invitation to join the Oulipo by more than a decade. Now, what does it mean to read the first English translation of such a novel, which teases out all our assumptions about identity, love, desire, relationships, with almost sacramental intensity?

We can, at least, trust in the simple counsel of the novel’s translator, who (after Garréta) made our reading possible in the first place: “If our pre-conceived notions about all of these things are defied by this text, what does that say about our pre-conceived notions? Reading Sphinx is one way to think about these questions, to question our ways of thinking.” Whether in spite of or due to its preciousness, Sphinx serves to remind us that it is us who are still woefully behind the times.

***

MB: First, I want to enquire about the context that instigated an English translation of Garréta’s novel now. Sphinx was published in 1986—when Garréta was only 23 years old. What made the impetus for this translation—nearly thirty years later—so urgent?

ER: Well, when I first found out about Sphinx, I heard about it in the context of Daniel Levin Becker. He wrote a book about Oulipians, and he briefly mentions Sphinx, and I assumed that it had already been translated. And then I went looking for the translation and I couldn’t find it, and when I realised it hadn’t been translated yet it just sort of seemed wild to me, you know, that no one had tried to translate this book. It was pretty wild to me that, despite the past, however many years going by since this book was published, it still feels very relevant, maybe more so now than then, because people are more interested in talking about gender and the way gender influences our lives, and influences our identities, the ways it kind of constricts us, and I feel now more so than in 1984—at least in the States.

READ MORE…