Rita Stirn is a translator, author, and musician who lives in Rabat, Morocco. Her book, Les musiciennes du Maroc: Portraits choisis (Morocco’s Women in Music: Selected Portraits) was published by Marsam in late 2017. Asymptote’s Editor-at-large Hodna Nuernberg spoke with Stirn about her new publication, Moroccan music, and language politics in the region.

Hodna Nuernberg (HN): How did you decide to write a book on Morocco’s women musicians? And how did being a woman musician yourself shape your approach to researching and writing the book?

Rita Stirn (RS): I’ve always been interested in the silences of history concerning women in art and music. When I started listening to the blues as a teenager, I realized music was a man’s world. Sure, there were plenty of female singers, but very few instrumentalists; I wanted to learn about hidden talents—the women in music who weren’t getting much recognition.

I came to Morocco in 2011. I paid a lot of attention to what was going on here musically. Whenever there was a celebration out on the streets—a marriage, for example—there were inevitably women playing music. So, I’d talk to them. They’d say, “Yeah, sure, people know us,” but none of them were online anywhere. They got all their gigs by word of mouth, and little by little, I began to find out about more and more women musicians.

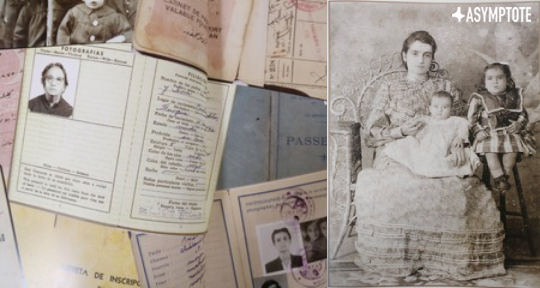

Around the same time, I was looking though archives for photographs of women in music. All the images were of men. There was no focus whatsoever on women’s talents or the tradition of women instrumentalists, and that’s when the book project started to take shape in my head.

READ MORE…