Myriam Moscona’s Tela de sevoya (Onioncloth) was published in English in 2017, translated from the Ladino by Antena (Jen Hofer with John Pluecker). In today’s essay, Asymptote’s Sergio Sarano, himself a Ladino speaker, uses Moscona’s book as a starting point to explore the language and its history, shaped by the complex migrations of the Jewish diaspora. Sergio also discusses Ladino’s current status as an endangered language and highlights the important role that Moscona, as one of just a few writers who continue to publish in Ladino, has to play in keeping the language alive.

“I come upon a city

I remember

that there lived

my two mothers

and I wet my feet

in the rivers

that from these and other waters

arrive to this place”—Myriam Moscona

- In 1884, a Yiddish newspaper printed a beautiful description of its language. Now, to describe not Yiddish but Ladino (a.k.a. Judaeo-Spanish, Judezmo, Djudio, Spanyolit, Sephardi, etc.), one of the many languages spoken by the Jewish Diaspora, born after the 1492 expulsion of Jews from Spain, I will appropriate this simile. Thus, Ladino “consists of Old Spanish, altered like an old coat, with the lining patched with Turkish and Arabic and Greek, and with the outside fabric adorned here and there with the ribbons of Lashon HaKodesh [Hebrew].” And, might I add, with elegant French, Portuguese, and Italian buttons.

- In 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain issued the Alhambra Decree, which gave the Jews living in their domains four months either to convert or to leave, under the threat of summary execution. The numbers vary, but up to 100,000 Jews may have left Sepharad—the traditional Hebrew name for the Iberian peninsula—migrating to North Africa, the Ottoman Empire, Italy, the Netherlands, and the Americas. They were only allowed to take whatever they could carry, so they took their language, their songs, and their recipes. Some brought their house keys, in case they ever returned. Sephardic Jews still commemorate the tragedy on Tisha B’av, the saddest day of the Jewish calendar.

- Ladino is not a Spanish dialect—it is a daughter of Old Spanish. Antonio de Nebrija published his great grammar of the Spanish language—the first one among the European vernaculars—as early as 1492, the year of the Expulsion and Columbus’ travels. Nebrija said language could be “the instrument of the empire,” forgetting that it could be the instrument of resistance and survival, too. A man interviewed in Tela de sevoya, Souhami Renaud, says that “Judezmo is like a thin strand of silk that ties us all together.” Unfortunately, it is the opinion of many that this thin strand is getting even weaker and that it might break.

- In the opening paragraph of Borges’ short story “The Immortal,” Joseph Cartaphilus of Esmirna is reported to speak a curious blend of languages, including español de Salónica. 90% of the Ladino-speaking population was murdered by the Nazi regime, most of them Jews from Thessaloniki, Greece. It was once called the Jerusalem of the Balkans. Yehuda Haim Aaron Hacohen Perahia wrote a poem on March 17, 1943, painfully recalling the night he barely managed to escape death in Bulgaria: “My brain tears apart, my mind is troubled and refuses to reason./ Human intelligence refuses to function before this evil.” There is an old Sephardic saying, which is actually the epigraph of Tela de sevoya, that says: el meoyo del benadam es tela de sevoya, the human mind is like an onioncloth: fragile.

- The Moscona family left Bulgaria in 1941 and wandered through several countries, ending up in Mexico City. Just as her family did, Moscona’s book travels through different genres—memoir, travel diary, poem, interview, even a delicious recipe—but it never really settles. My favorite episode is the visit of Nissim Karmona, Myriam’s relative, in 1957 to a Mexican radio station. During his visit, he fooled a confounded host into thinking the harmonica he had brought to the studio was called shorra in Ladino, which is the vulgar word for penis. The prank reached the rabbi’s ears, and he decided to punish Nissim. Eventually, Nissim had so good a revenge on the rabbi that I can’t give it away in this essay.

- Tela de sevoya is, on the one hand, a story of recovery, of a woman finding her two mothers. Myriam the narrator (who is not the same as Myriam the author) travels back to Spain, Bulgaria, Greece, and Israel in search of lost time. Her work is strongly Proustian. One of the poems mentions her reading Proust’s second volume. In a sense, this is a book of interwoven desires that do not always satisfy themselves. In Sofia, the narrator writes: “The address, 33 Iskar, has been engraved in my memory for years. If someone were to rouse me from my sleep to repeat that address, I would do so with no hesitation.” Once Myriam arrives at 33 Iskar, she will feel at once relief and disappointment. The Ladino language has etched on her tongue the addresses of countless houses in the Jewish Quarters of Toledo and Burgos.

- On the other hand, Tela de sevoya is a tale of grief and loss. Myriam recalls: “The night of that same day, my mother tells us that in her wardrobe she keeps that yellow star they had to use to identify themselves as Jews in Sofia.” There is another unforgiving scene in which little Myriam is told by her dying grandmother, Victoria, “For an evil little girl like you there is no forgiveness.” The sorrow that follows Victoria’s death is deep, lingering forever in Myriam, just as the grief of the Expulsion lingers in her language, already present in the apocryphal letter signed by Don Isaac Abravanel, legendary leader of the Jewish community, imploring the King and Queen of Spain to rescind their cruel Edict.

- There is a Hebrew word, zakhor, which means memory or remembrance. In Judaism, remembrance is a commandment. On a certain Shabbat, a portion of the Torah is read out loud that says: “Do not forget!” Moscona writes: “The only form of translation to which memory has access is language.” By writing Tela de sevoya, Moscona is fulfilling the commandment of not forgetting. She allows memory to live through la lingua florida, the flowery language. Gone people and cities come back to life and sing in unison with Moscona’s book. Torno i digo ke va a ser de mi/ en tierras ajenas yo me vo morir. I return and say what will become of me/ In alien lands I must die.

- To read Tela de sevoya in translation offers an exciting experience. When read in Spanish, Ladino glows differently, since the two languages bear great resemblance. However, when surrounded by English words, Ladino acquires a whole different color, and the solution to retain the Ladino text while providing an immediate translation (in the original, the Ladino remains untranslated) is quite successful. Antena’s Jen Hofer and John Pluecker have done a remarkable job in preserving the tenderness of Moscona’s prose, and the sections in verse are stunning. I would love to see an Antena translation of other contemporary works in Ladino.

- It is a little known fact that Elias Canetti, the winner of the 1981 Nobel Prize in Literature, who wrote in German, grew up in a Bulgarian Ladino-speaking home. After leaving Austria, he wrote: “At 33 I had to leave Vienna and took German along with me, the way they did with their Spanish. Perhaps, I am the only literary person in whom the languages of the two great expulsions is found in such close proximity.” We are told that, while still in Bulgaria, the Mosconas were acquaintances of the Canettis. Almost nothing is left of the more than one hundred Ladino newspapers and journals, libraries, and cultural groups that flourished in the early twentieth century.

- Every Monday night at the Spanish & Portuguese Synagogue of New York, Rabbi Nissim Elnecavé would have us read out loud portions of the Me’am Loez, the long commentary on the Hebrew Bible written in Ladino by several rabbis throughout the eighteenth century, considered the most important text in the language. I remember the time he told us the story of the Oven of Akhnai, in which Rabbi Eliezer argues with the rabbis over the status of a new kind of oven. After a carob tree, a stream, the walls of the study hall, and heaven itself prove R. Eliezer’s opinion, R. Joshua responds: “The Torah is not in heaven.” What R. Joshua meant (according to some) is that the law is constantly created through human interaction, as opposed to existing in some unreachable beyond. Memory, too, is constantly created through reenactment and writing—it is not an unchanging thing. Moscona understands this very well. I try my hand at it, and read out loud the same xeroxed pages of the Me’am Loez; those nights come to me as though I had never lived them.

- Me akodro de las nochadas del meldar

I son komo pedrikas

Ke arrondjo a un podjo

I supito trokan en montanya

En tokando el fondo.

I remember the nights of study

And they are like pebbles

I throw into a well

And suddenly turn into a mountain

As soon as they hit the bottom.

- Ladino is an endangered language, with only 130,000 speakers left according to Ethnologue, mostly found in Israel, the United States, and Turkey. A grim paper by Tracy K. Harris reports that “there are very few fluent Ladino speakers today under the age of sixty.” Google Translate includes Yiddish but not Ladino, and no internet browser offers a language pack. However, there is a Ladino Wikipedia (I wrote the article on Yitzhak Navon, a great promoter of the language.) Recently, the National Ladino Academy was created in Israel to preserve the language. The University of Washington is doing fantastic archival work to keep Ladino vibrant, and a few authors are still writing in Ladino, keeping the thin thread from breaking: Margalit Matitiahu, Matilde Koen Sarano, Denise León. I’m sure that as long as los trezoros, the treasures, of Tela de sevoya continue to be read, the thread will not break.

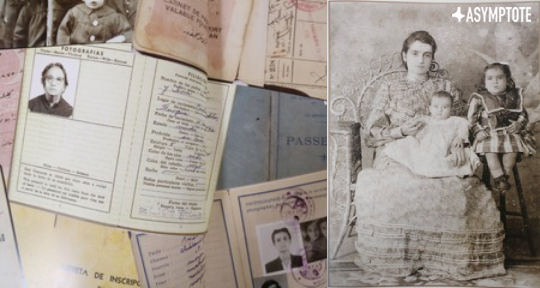

Photo credit: Centro de Documentación e Investigación Judío de México (CDIJUM) and Raquel Castro

Sergio Sarano is Spanish Social Media Manager at Asymptote and Editor-in-Chief at Meldadora. He lives in Monterrey and is currently translating Testimony by Charles Reznikoff.

*****

Read more essays on the Asymptote blog: