Many translators might agree that language is song, a kind of mouth music. Each text has a unique time signature and timbre, and when we translate voice, we have to open our ears before opening our beaks to become songbirds. And translators have a special insight into how a language’s sounds are made up of tones: pitches that help to convey meaning. A toneless voice, whether spoken, written or translated, is like a song without melody.

I learnt recently that mouth music is the alternative name for lilting, the subtle rise and fall of words in a sentence, and originally a style of Gaelic singing. Given that the nitty-gritty of literary translation is the picking up on nuances in voice, it strikes me as odd that translators, myself included, don’t dedicate much airtime to lilting. Why don’t we talk about lilting when we talk about voice? Isn’t it odd that translation theorists—boasting the loftiest and loveliest buzzwords in all the humanities—haven’t yet adopted it? After all, lilts are not merely ephemeral: a good prose stylist (and good translators too) can conjure them in writing. In James Joyce’s Dubliners, “The Dead” presents a good example of a lilt woven into a text, one that reverberates off the page when read aloud:

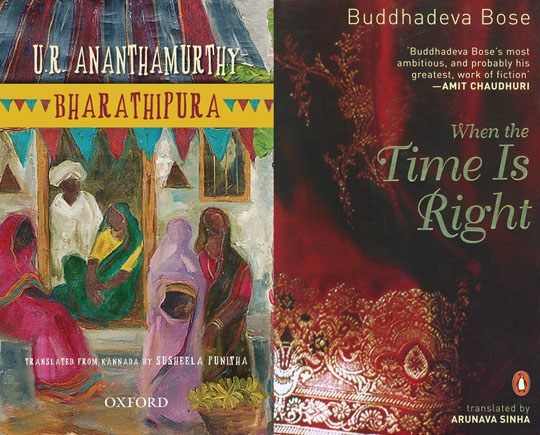

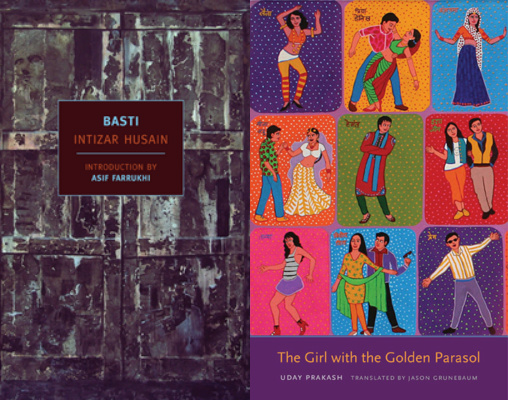

It’s Time to Talk: On Translations from South Asian Languages

Mahmud Rahman concludes his insightful series by addressing your questions and responding to the discussion he sparked.

Read all posts in Mahmud Rahman’s investigation here.

In this final post, I want to respond to some issues that have come up among readers. Besides a few comments on the blog posts, this series also generated conversations that came to me via personal emails or messages on Sasialit, a mailing list about South Asian literature.

Huizhong Wu, a literature student at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote me:

READ MORE…

Contributor:- Mahmud Rahman

; Tags: - comments

, - discussion

, - South Asian languages

, - South Asian literature