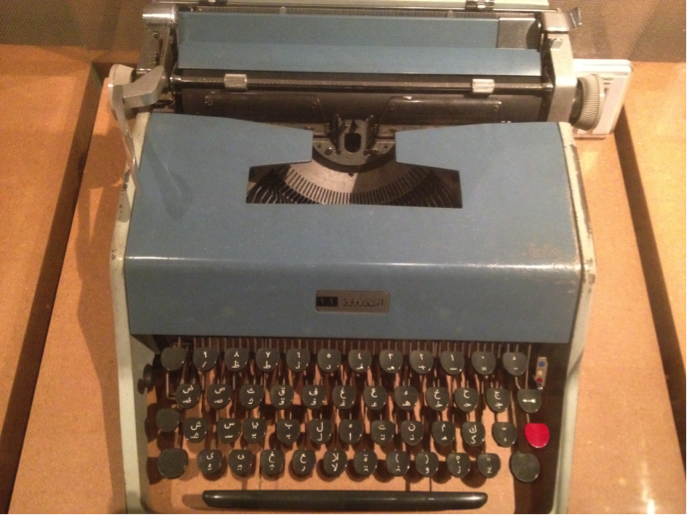

Arabic Typewriter

Manufactured: c. 1966

Height: 5.9 inches, width: 15 inches

On display at the Malay Heritage Centre, Singapore

Jawi, an Arabic alphabet, was the dominant form of written Malay in Malaysia and Singapore for more than 600 years, but these days it’s in danger of becoming as obsolete as the typewriter.

Though the Malaysian ministry of education attempted to revive Jawi learning in the past—in 1970, elementary schools began teaching Jawi, and soon after high schools followed suit—by 1981, when I started Standard One (Malaysian first grade), Jawi was no longer part of the national curriculum. By 2006, Malaysia’s only remaining Jawi newspaper, the Utusan Melayu, which first appeared in Singapore in 1939, had ceased publishing.

As a translator of Malay into English, I’ve long been interested in Jawi, and when I spotted what I thought was a Jawi typewriter at the Malay Heritage Centre (MHC) in Singapore, I was immediately curious. I wanted to know where it came from, how old it was, who had owned it, how it was used. What follows is the conversation I had with the MHC concerning its typewriter, carried out over email. Noorashikin Zulkifli, Head of Curation and Programs at the MHC, helped trace the typewriter’s origins and explained its features. Encik Syed Ali Semait, Managing Director of Singapore-based Pustaka Nasional Pte. Ltd, the publishing and typesetting company that donated the typewriter to the MHC in 2012, helped identify the typewriter’s original owner.

Nicole Idar: To whom did this typewriter belong?

Encik Syed Ali Semait: I have to clarify that this is an Arabic typewriter, but it would also have been used for Jawi writing. The typewriter belonged to my father, Ustaz Syed Ahmad Semait (1933–2006), a religious teacher, editor, and translator of Arabic materials into Malay; he founded Pustaka Nasional in 1963. [My father] bought the typewriter in the 1970s in Cairo, and used it to write letters, primarily to Middle Eastern publishers and Arab writers.

NI: When was the typewriter produced, and who is the manufacturer?

Noorashikin Zulkifli: On the front of the typewriter, the manufacturer’s label is printed in Arabic to spell “Underwood.” This would have been an imprint under the Olivetti brand. The model is No. 21, which would have been issued around 1966.

NI: If the Underwood is supposed to be used as an Arabic typewriter, can it really be used to type in Jawi? After all, Jawi is a slightly modified version of the Arabic alphabet.

Noorashikin Zulkifli: In Jawi, several letters are added to the standard Arabic alphabet to accommodate Malay sounds (such as the “p,” “ng,” and “ch” sounds). These additional letters were borrowed from the Persian form of the alphabet. Standard Arabic has 28 letters; Jawi has 32.

I do know that the Arabic alphabet itself was modified (made more uniform, I believe) to allow for its use in typographical and typesetting processes.

At first I didn’t quite believe that the typewriter could effectively type in Jawi. There are approximately 3 forms for each Arabic letter (depending on whether the letter appears at the beginning, the middle, or the end of a word), so you would need 84 keys for standard Arabic—42 physical keys with lower and upper cases. For Jawi, you would need 48 physical keys with lower and upper cases. Added to that, you would need keys for numbers, 0–9, as well as punctuation marks.

The keyboard of this typewriter has 43 physical keys to cover the alphabet, numerals and punctuation marks, excluding the return, shift, and tab keys. And this is a fairly standard keyboard size. Upon closer examination, we can say that this keyboard can indeed produce all 32 letters used in Jawi in its different forms.

Arabic numerals only have one form (i.e. no upper/lower case/change in shape according to position), so the lower cases of the numeral keys cover the remaining forms of Arabic/Jawi letters. I must say it’s a design marvel.

NI: The carriage return lever is on the left, just like in a conventional typewriter, so it looks as if the typewriter types from left to right. But Jawi, like Arabic, is written from right to left. How would a typist wanting to type in Jawi or Arabic use this machine?

Noorashikin Zulkifli: The operation of the machine does seem to contradict the possibility of typing in Arabic/Jawi. We cannot be sure, as Encik Syed Ali himself confessed to not knowing, but there are two possibilities for how this machine would allow for right-to-left typing:

1. The mechanism has been inverted, so that while the lever remains where it is, the carriage would move in a right-to-left fashion. Meaning that instead of using the lever to return the carriage to the beginning (i.e. right margin), you would use the lever to pull out the carriage to the left, and then when you type, the carriage would return to its normal position.

2. If there is no inverted mechanism and the carriage still kicks out to the left, and typing must move from left to right, then the typing is done backwards. I know this sounds very counterintuitive and completely inefficient, but I have seen footage of a user on a similar typewriter, and it was exactly that. Typing done backwards!

NI: Were Arabic typewriters like the Underwood used in Jawi publishing?

Noorashikin Zulkifli: It is quite probable that typewriters like these would be used more for letter-writing and the preparation of manuscripts. My educated guess is that typewriters would have been used from the 1950s-1960s on. Part of my reasoning is that early Malay printers and publishers (as well as other Muslim publishers in India, for example) did not favor typography, or printing using set keys, because it produced what was perceived to be an ugly version of Arabic/Jawi: too regular, too uniform. It did not allow for the calligraphic flair artistry that the Jawi manuscript tradition is known for in the region.

The more favored method was lithography, which allowed for traditional scribes to “keep their jobs” so to speak. The earliest use of typography might have been by Christian missionaries, who had commissioned the translation of the Bible and other material into Jawi during the 19th century, but this process would have used a press, and not typewriters.

From what I have come across, you would see typographical Jawi being used as the mainstream method around the 1950s onwards. I think this would have provided enough time for advances to be made in printing technology, distribution, and circulation of presses and typewriters to culminate in a widespread industry practice.

Encik Syed Ali Semait did explain that before Pustaka Nasional started using computers in the 1980s, they used typewriters and typesetters to produce text in Jawi and Arabic, which would then be physically laid out and composed on a page. The page layout would then be photographed and converted to film for offset printing.

NI: When did the Roman alphabet take over from the Arabic alphabet in written Malay?

Noorashikin Zulkifli: For Singapore and Malaya [Malaya was renamed “Malaysia” six years after independence in 1957], it was a conscious and concerted decision to switch to a Romanized form around 1957-59, as part of a nationalist/independence movement where Malay was championed as the national language.

In an effort to make [the Malay language] more accessible to non-ethnic Malays, the Jawi-to-Rumi decision was taken up at the 3rd Congress of Malay Language and Letters held in Singapore and Johor. Publications would have been in Jawi all the way through the 1950s, tapering off in 1960s, and completely in Romanized form by the 1970s to the 1980s, except for the publication of religious texts, when Jawi is still used.