This month, we bring you thirteen reviews from thirteen countries: a poetry collection that reimagines friendships with long-gone revolutionaries, a tender and incisive rumination on disappearance, the latest novel on the inexplicability of love from a Nobel laureate, a story of Silicon Valley-fueled descent, a compilation of Latin American feminist thought, and much much more!

Duels by Néhemy Dahomey, translated from the French by Nathan H. Dize, Seagull Books, 2025

Review by Timothy Berge

Néhémy Dahomey’s Duels is set in 1842, thirty-eight years after Haiti’s independence—a storied liberation that came through one of the largest slave uprisings in history. France withdrew, but issued an absurd debt of one hundred and fifty million francs. Paying off a debt while attempting to modernize a new country was a tough balancing act, so Haiti imposed high taxes on its citizens and forced them into unpaid labor.

Duels takes place in Böen, a small town in the Cul-de-Sac Plain that evaded a census for several years. As a result, no one in the town had fallen victim to the government’s schemes—until a local official decides that he needs laborers for a new project. From there on, in the context of freedom, economic entrapment, and postcolonial growing pains, the events of Duels unfold. Nathan H. Dize’s translation reads like a yarn spun out by an old relative with a deft deadpan humor, aptly navigating the tense shifts between past and present, and generating a sense of perpetuity for these characters and their stories. Here, the historical and the contemporary connect and blur.

At the center of the story is a wealthy notary named Ludovic Possible, who runs a school in Böen—primarily with the motive of getting close to his illegitimate daughter, Aida. When a two-week long rainstorm hits the region, Aida’s mother, Gracilia, dies, and Ludovic reveals himself as Aida’s father, taking over her care. Yet, what truly drives Dahomey’s narrative is the tenets of community and storytelling. Ludovic falls in love with Gracilia because of the way she tells stories, and she passes these tales to Aida; before the child was born, Gracilia “. . . placed a hand on her lower abdomen and told her fertile ovaries the very first story she’d learned from her own mother, who’d learned it from her grandmother, who’d learned it from her great-grandmother. . .”—and so on, all the way back to their first ancestors. Fittingly, the story itself is about a chantrèl who was admired by all: “When she spoke, things would happen. When she made demands, people got to work. With her voice, the rapture caused men to fear for their own sanity.”

Aida internalizes the story and, after her mother’s death, becomes the chantrèl. Armed with the tales passed down from her mother, the young girl builds and fortifies a circle of people who will come to care deeply about her, who will fight on her behalf. Building on the singular capacity of stories to bring people together, Duels captures their particular power within the historical context, demonstrating how the act of telling can frighten those in power and liberate those in captivity.

Whether against an elemental antagonist or a human one, the people in Böen unite to enact change through rebellion. As Duels connects the creation of such solidarities with storytelling, it also works to help the citizens of a tumultuous country imagine a future where violence, injustice, and exploitation no longer govern—necessary work for any nation undergoing immense transformation.

Diving Board by Tomás Downey, translated from the Spanish by Sarah Moses, Invisible Publishing, 2025

Review by Regan Mies

In “Astronauts,” one of the nineteen stories in Tomás Downey’s Diving Board, a man floats to the ceiling and stays there. Why? “Chance is capable of anything,” the narrator concedes. “The universe lacks a will—it just exists, occurs.” Characters across the collection are self-proclaimed skeptics—suspicious of friends and family, their own inclinations, and most strongly, when faced with the inexplicable. In the Argentine writer’s hands, such individuals are a way of exploring the possibilities of universal chance or malice. Facing apparitions or aliens or human urges toward the unforgivable, they try to grasp at the logic of their worlds—and fail.

“It was a question of equilibrium,” the narrator of “Variables” thinks, justifying the increasing, startling neglect of her child as she works from home postpartum. Balance was as simple as “removing something from one side and putting it on the other.” In “Alejo,” a teen steals a scalpel during a lesson on frog dissection to harm a female classmate. Only later, covered in blood, does he realize: “Between desire and action there should’ve been a step, one he had skipped. He’d followed a different logic and that made everything seem more unreal.”

Logic, whether between the members of nuclear families or partners in perfect couples, becomes twisted and distorted in Downey’s dire chronicles. Stories are quick glimpses of lives, their characters cut off before consequences have the chance to set in. I felt my pulse race while reading the final lines of “A Love Story,” about a couple’s weekend trip to a remote cabin where the running water doesn’t work; my stomach sank with each paragraph of “The Place Where Birds Die,” about how a new baby alters a family summer at the beach.

Tomás Downey has mastered the chill in the air, the prickling at the back of your neck; in Moses’s translation, colloquial and keen, these stories could be told by your neighbor or cousin. Recurring instances of the surreal—disappearances, repetitions, the supernatural and unexplained—heighten the characters’ more routine circumstances and recalibrate the way they see the world. Here, the gore, rot, and dread are tools for examining how we deal with the real horrors in our lives. As the narrator of “The Men Go to War” offers in the stead of seeking relief in tragedy’s wake: “Better to hold on to the raw pain that’s perpetual but bearable, like a child who’s sick and in need of constant care.”

The Sea and Poison by Shusaku Endo, translated from the Japanese by Michael Gallagher, Pushkin Press, 2025

Review by Timothy Berge

How does someone come to participate in atrocities? This question is at the center of Shusaku Endo’s 1957 novel, The Sea and Poison, which addresses the dilemma through a medical student named Suguro. In the midst of World War II, he and another student, Toda, are asked to help with a surgery that seeks to determine how much of a lung can be removed from an American prisoner before he dies—a vivisection based on actual experiments performed by Japanese doctors during the Second World War. For Endo, a lifelong Catholic, this narrative is used to suggest that people enact atrocities because they base their morality on societal mores rather than on a higher power. Without belief in a transcendent morality, people like Suguro and Toda are able to conform to and excuse anything.

After the vivisection is complete and the American prisoner is dead, Suguro expresses fear to Toda about having to answer for what they have done. Toda responds dismissively:

Answer for it? To society? If it’s only to society, it’s nothing much to get worked up about. . . . You and I happened to be here in this particular hospital in this particular era, and so we took part in a vivisection performed on a prisoner. If those people who are going to judge us had been put in the same situation, would they have done anything different?

This is Toda’s belief—but Mrs. Hilda, the German wife of the hospital’s lead surgeon, is a counterpoint. In a scene where a patient is dying and a nurse is about to administer procaine (a medication that will kill her quickly and painlessly), Mrs. Hilda intervenes: “Even though a person is going to die, no one has the right to murder him. You’re not afraid of God? You don’t believe in the punishment of God?”

Essentially, the morality question is answered in The Sea and Poison through the juxtaposition of cultures; whereas the Japanese medical staff base their morality on circumstance and societal norms, leading them to murder, the only European character bases her ethics on the divine. In doing so, the novel portrays religious faith as both a cultural phenomenon, but also insists that such convictions are above culture. This paradox characterizes The Sea and Poison as a relatively early effort by Shusaku Endo to engage with the complex issues of belief and morality that populate his later works—but most importantly, represent the writer’s attempts to grapple with some of the most pivotal and confounding issues of his time: that of responsibility and evil amidst the postwar readdressing of Japanese society.

Things That Disappear by Jenny Erpenbeck, translated from the German by Kurt Beals, New Directions, 2025

Review by Regan Mies

Booker Prize-winning author Jenny Erpenbeck’s oeuvre has thus far featured an East German romance as the Berlin Wall goes down; the portrait of a country home as generations of occupants experience war and political transformation; and a community of African migrants seeking asylum in Berlin. In her newest book to be published in English—a slim seventy-page volume—Erpenbeck’s steadfast focus on loss and change is even more explicit across a series of fragmentary essays.

These pieces take the shapes of conversations, meditations, even step-by-step instructions. How does one go about demolishing a house? Where have our missing second socks ended up? Throughout, themes of destruction and disappearance span the intimate, political, and existential. Drip-catchers on tablecloths, courtyard rug hangers, the shop that mended tights: Erpenbeck writes of things disappearing when they are “deprived of their means of existence, as if they, too, have a hunger that must be satisfied.”

But what about entire nations that have ceased to exist—where are they? Where, too, are our family’s traditions when we no longer celebrate them? On youth, Erpenbeck writes, “. . . we’re taken by surprise when the years have slipped over us like a dress, and we think that actually, if we wanted to, we could take them off again. . .” We disappear from the places we’ve inhabited; the people we love disappear from us. In Kurt Beals’s delicate translation, Erpenbeck’s prose is compellingly earnest and solemn, and quite playful in moments, without ever straying toward over-sentimentality.

In one vignette, a Russian immigrant visits Erpenbeck’s apartment, cluttered with the decades-long accumulation of objects and ephemera. The woman exclaims at the piano, the books, Erpenbeck’s son’s drawing, “Lovely.” Erpenbeck doesn’t understand her awe—she has children, as well, and so must have similar things. The woman smiles. “You can’t take it all with you,” she says. Things That Disappear is a collection that seemed to slip through my grasp, however much I wanted it to last. Upon reaching the end, I found myself thinking: if only I’d held on tighter.

The Innocent Days of War by Mario Fortunato, translated from the Italian by Julia MacGibbon, Other Press, 2025

Review by Eva Dunsky

Interrogating what happens when war interrupts our intimate lives, Mario Fortunato’s The Innocent Days of War takes place in a small and isolated village an hour’s journey from Rome, where Eleanora and Stefano are cocooning into their life together as besotted newlyweds. The world is on the eve of the Second World War, Italy is devolving into factions, and Stefano—a stuffy academic by day and anti-fascist agitator by night—finds individual purpose and a connection to the larger world in his activism.

The idyllic and idealistic days of Stefano’s youth end abruptly in the novel’s second chapter when Eleanora dies in childbirth and war breaks out. The family then decides her younger sister Nina will marry Stefano instead, solving the question of how the impoverished family will pay her dowry. However, it’s immediately obvious that Stefano and Nina aren’t a match; Nina is a young and fiery teenager, conducting a secret affair with Sergio, another teen from their village who joins Stefano’s antifascist cause. Stefano himself is strung by grief, leading him to retreat further into his books.

Meanwhile, their lives intersect with those of Alastair Ormiston and his best friend Edna, who both serve in the British army and find themselves fighting in Italy. Similarly to Stefano, Alastair is devoted to the solace he finds in literature, making sense of the world through Virginia Woolf’s novels. These characters all encounter each other in wholly unexpected ways—and ones that have little to do with the political allegiances they’re meant to be upholding. In this, Fortunato highlights how arbitrarily these grand forces intersect with the lived realities of actual people, masterfully capturing the chaos of wartime before the official historical narrative is to be crafted and retrospectively imposed: “After all, the future is what happens once a story has come to an end, and stories often aren’t keen to announce that.”

Vaim by Jon Fosse, translated from the Norwegian by Damion Searls, Transit Books, 2025

Review by Timothy Berge

Vaim is the first novel in a new trilogy by Jon Fosse, and many characteristic elements of the Nobel laureate’s work are present: a lonely man with a boat, a trip from the rural Norway countryside into the city, long internal monologues, very little plot, and porous borders between dreams and reality, between life and death, between the self and others—all composed in an elliptical and meditative prose rendered beautifully in English by Damion Searls.

The novel opens with Jatgeir, a fisherman visiting Bjørgvin (an old name for Bergen), who just overpaid for a needle and thread when he runs into his childhood crush, Eline, on the dock near his boat. Eline wants to leave her husband, Frank, and move with Jatgeir back to their hometown, Vaim. Jatgeir obliges.

Encountering Eline is dreamlike for Jatgeir: “. . . everything felt so unreal, yes, like it couldn’t be anything but a dream, but it wasn’t a dream, I was standing right here as wide awake as can be on the deck in the cabin of the motorboat. . .” His phantasmagoric run-in then becomes ineffable once they touch: “. . . Eline grabs my hand with such feeling, so warmly, and it’s like the warmth from her hand runs through my whole body, in a way I’ve never felt before either, this warm feeling through my whole body was new to me, I think, and it’s a feeling I can’t name, it can’t be said in words. . .” This unspeakable touch fundamentally changes Jatgeir; the two become one in a simple exchange.

Eline and Jatgeir live together until Jatgeir’s death years later, upon which Eline returns to Frank, persuading him to move to Vaim with her and live in Jatgeir’s house. Frank obliges, as similar to Jatgeir, Frank finds being with Eline beyond understanding, his will folds into Eline’s: “. . . I think that this is totally incomprehensible, but it’s like I have no choice, no will of my own. . .” Once again, two become one.

For Jatgeir, life with Eline was dreamlike; for Frank, it’s strange. “. . . I’ve thought about Eline and me for all these years, I’ve never come up with any explanation other than that everything was strange. . .” Both men are fishermen living simple lives in a small town, but their lives are turned upside down through human interaction. Their relationships render existence into something alien, dreamlike, and transcendent. While Frank and Jatgeir never meet, their lives and deaths are entwined through Eline. Like the needle and thread that Jatgeir purchases, she sews together the fates of lonely fishermen into one vast mystical garment.

Earthly Conditions: Selected Poems by Birhan Keskin, translated from the Turkish by Öykü Tekten, World Poetry, 2025

Review by Sofija Popovska

To write about anything on Earth is to write autobiographically, because the self is entangled with everything else through chemicals, love, and violence. Birhan Keskin’s Earthly Conditions channels the awareness of this deep connection between oneself and the world—animals, plants, landmasses, bodies of water—through a lyric whose ambiguity fosters multiplicity but not abstraction.

“i don’t want the word to be spoken, the depth to be damaged,” Keskin writes, and indeed the terse ambivalence of her verse leaves the richness of its meaning intact. Öykü Tekten’s choices as a translator are equally instrumental to this—for instance, her decision to leave the gender-neutral Turkish pronoun o in “Seashell” untranslated to preserve its indeterminate referentiality. Gendered English pronouns would facilitate yet limit understanding—Keskin did not intend to clarify whether the speaker encounters “a person, an animal, another seashell, [or] waves.” Embedded in an English text, the Turkish o loses its linguistic specificity and assumes a symbolism congruent with its shape: circular and all-encompassing.

Only such a pronoun can convey that turbulent and formative encounter with a kaleidoscopic other. We are constantly being transformed by everything in the world; o’s ambiguity thus allows it to stand for multiple beings simultaneously and evoke many intimacies without typologizing them as deep or transient, gentle or violent. Involvement is rarely so definitive. In “Seashell,” o extracts the speaker’s mother of pearl in a process that is both forceful—“o took me away from the shore”—and intimate (in the way of Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons)—“o felt up my mother of pearl.” Displaced by o, the speaker finds themselves in a hostile environment: “in deep seas, in cold seas / i grappled with salt with waves. . .,” yet discovers joyfully that they are “. . . not a cold stone anymore / who curled up inside and forgot its own dream,” culminating in a realization of vitality and receptivity possible only within connection.

This connection, while enriching, is not comfortable or innocuous. Entanglement opens us up to the devastation of severance; Keskin allows it to do so. “i am nailed to your absence,” laments the speaker in “Caterpillar,” experiencing separation as a species of death: “if the world still spins around / it does so without me”. With an aching intensity that rips the soul asunder and reassembles it as part of a greater world-body, Birhan Keskin’s poetry is truly a force of nature.

Mothers by Brenda Lozano, translated from the Spanish by Heather Cleary, Catapult Books, 2025

Review by Eva Dunsky

In Brenda Lozano’s Mothers, translated by Heather Cleary, the author deftly subverts any preconceptions the reader might have about morality. While the narrative begins with one mother’s grief after the kidnapping of her two-year-old daughter, Gloria Miranda, it then veers off to tell the story of Nuria, the daughter’s presumed kidnapper—an increasingly desperate woman facing a possible divorce if she can’t provide her husband with an heir.

On one side of the kidnapping fiasco sit the bereaved Felipes: a matriarchy of women who’ve ascended Mexico City’s social order and have nothing but time and money to throw at the problem of their youngest member’s kidnapping. This is largely due to the industriousness of Ana María, Gloria Miranda’s grandmother, who epitomizes the rags to riches narrative. Having fled a marriage under horrifically abusive circumstances, she used her wit and craftiness to build one of the top fashion empires in the world and earn a fortune—not to mention a reputation as one of the few powerful, visible women in her ambit.

Her daughter, Gloria Felipe, has always felt the pressure of such a remarkable mother while also struggling with the sense that she isn’t a priority and that the only way her mother can show love is through money. Throughout, we’re faced with the question of whether or not money—always of tantamount importance, but especially in 1940s Mexico City—will be enough to solve this problem.

It’s significant that on the other side of the kidnapping, Nuria’s plot isn’t a sob story; having grown up as the pampered and sheltered only child of middle-class parents, she now lives with her husband and works in hospital administration. Coming up against the limits of her privilege—her able-bodiedness, her relative financial well-being, her more-or-less happy marriage—is what truly drives her crazy, and makes what might’ve been a simple story of haves and have-nots into something much more complicated and interesting.

Lozano eschews easy answers, instead playing with the reader’s sympathies at every turn, a murkiness Cleary does well to preserve in the translation. This novel is infused by loss and need: Nuria’s, Ana Maria’s, and of course, Gloria Felipe’s. These needs, while archetypal in some ways, aren’t ever intuitive. In a novel of traumatized women trying to forge lives for themselves amidst hostile patriarchal terrain, only little Gloria Miranda gets out relatively unscathed.

Sea Now by Eva Meijer, translated from the Dutch by Anne Thompson Melo, Two Lines Press (US)/Peirene Press (UK), 2025

Review by Mandy-Suzanne Wong

Sea Now, Eva Meijer’s latest novel, unfolds from both broad and intimate perspectives with a voice that, in Anne Thompson Melo’s translation, is delightful and terrifying in its simplicity. “It feels like a disaster movie, it feels like a dream,” says the novel of its own story, wherein the sea is reclaiming the Netherlands, at this very moment..

It isn’t just a human story, but one of overfished fishes learning not to be afraid; of shellfishes, birds, rabbits, and “sea-being”; of horses discovering that “what they mean by freedom [is] the seaweed that moves inside you”; of whether, like mussels and octopuses, “the sea dreams” . . . In its regard for other-than-human Earthlings—acknowledging that they exist, that our lives and stories are also theirs, that they engage in a porous exchange—Sea Now joins Meijer’s rich oeuvre of novels and philosophical meditations on multispecies coexistence.

One could read this novel as the story of two characters—the Netherlands and the sea—posing a question of each other: What am I? What and who is “the Netherlands”? What and who is “the sea”? The first question implicates uncomfortable stories of value: Who determines the status quo that decides who or what (a foreigner?, a painting?) deserves to be saved, who or what (a US-trained scientist?, the Dutch language?) would count as a loss? And as for the second question, beautifully pose it in inconclusive list-form poems, such as “The sea as dreamcatcher,” “The sea as desire,” “The sea as home.” The sea has “motives,” it is “alive”—and perhaps the Netherlands’ drowning is an oceanic word.

It is also a story of humanity. “The sea has invaded our land,” says the unnamed Prime Minister—as though water advancing a kilometer per day were analogous to imperialist conflicts. “The only way to conquer the water is together.” With sexism and racism intact, the PM and his cohort (“the men, sorry, the people who are ready to defend our land”) order the construction of larger dykes and cheerful lies. Other humans—including a climate activist, an oceanographer, a poet, and a Middle-Eastern immigrant—are living the disaster on the flooded ground while learning that no land is really “ours.”

Such an all-encompassing catastrophe can only be narrated in fragments: poems, aborted autobiographies, forcibly optimistic emails . . . Yet Meijer’s prose, in Melo’s hands, flows quietly with a consistent bittersweetness, and the novel’s pervasively dreamlike quality underscores the true horror of this entirely realistic scenario. Meijer and Melo’s illumination of the situation’s absurdities, applied with such a light touch, comes across as a poignant aspect of humans’ capacity “to prevent [ourselves] from giving up on the spot.”

Hail, Che! By Pak Jeong-de, translated from the Korean by Ed Bok Lee and Eun-Mi Yang, Black Ocean, 2025

Review by Liliana Torpey

Eduardo Galeano, a great Uruguayan writer of the left, once wrote: “Return to the joy of simple things: the light of the candle, the glass of water, the bread I share. Humble dignity, clean world that is worthwhile.” In Hail, Che!, Pak Jeong-de finds revolution tucked away in such simple things—in his case: cigarettes, coffee, stars, and soccer (but mostly cigarettes). In everyday rituals, the poet touches the pulse of human struggle and aspiration: “a cigarette is a revolution of creaturely writhing and heat.”

The entire collection seems to unfurl from an unending exhalation of smoke curling out of Pak’s window. From there, he imagines a space where all poets and revolutionaries coexist, forever drinking, smoking, and listening to Tom Waits on the jukebox. He names hundreds of them, weaving them into a shared dream for a new and beautiful world. His effusive, ever-forward-tumbling verses are therefore more concerned with the spirit of revolution than its enactment. The doors of his imaginary leftist dive bar are wide open, inviting some contentious figures—Woody Allen, Paul Gauguin, and Johnny Depp among them. Pak’s Radical Barbarians’ Band is a curious group with an intangible mission, resulting in musings and exaltations that are both exhilarating and frustrating to read. As he describes himself: “I rushed into the burning heat like a philosopher with the heart of a volcano jumping into the world’s essence.”

Cigarettes in hand, Hail, Che! reads both as a performative exercise and a meditation, repetitively invoking symbols that embody freedom, solitude, and contemplation; the poet’s voice at times carries the melancholy nostalgia of the retired rebel who has set down his arms, living out his days remembering old comrades. Still, from the poet’s surrender springs an absurdist hope: “I grasp the futility and become heat to infiltrate the insides of the world”—like cigarette smoke inside a lung, perhaps.

All revolutionary movements must imagine a world to fight for, and surely, not everyone will envision the same one. In Hail, Che!, Pak shares a glittering vision of the world that, for him, proves worthwhile. Ultimately, it’s one of interconnectivity from which sparks of solidarity are forged, like asking a stranger for a lighter simply to make a friend.

Spent Bullets by Terao Tetsuya, translated from the Chinese by Kevin Wang, HarperVia, 2025

Review by Eva Dunsky

Terao Tetsuya’s Spent Bullets follows a cohort of Taiwanese engineering graduates as they rise through the ranks of Silicon Valley. It starts off simply enough: Jie-Heng, by far the most promising in his class of gifted students, inspires the envy, rage, and despair of his classmates. In adulthood, his peers watch from afar as he becomes the undisputed wunderkind of Silicon Valley, then dies by suicide after jumping from his hotel room window in Las Vegas.

The rest of this interlinked collection of short stories follows his former classmates as they try to piece his life together amidst the disappointment of their own. Jie-Heng’s short and tragic existence is recounted mostly through the perspective of Wu Yi-Hsiang, the childhood bully who recognized and fomented Jie-Heng’s desire for debasement over the course of their love affair. Each character holds a slightly absurd view of success—more and more money and status, at the expense of all humanity and happiness—but they grapple differently with this definition and comes away uniquely unsatisfied, either seeking out increasingly extreme ways of feeling alive or, in some cases, choosing not to continue living.

Wang’s translation is perfectly calibrated; as he points out in his translator’s note: “Parsing out the identities of the narrators is not easy when they all speak with a detached voice. Terao purposefully holds back from revealing their interiority, preferring to say more through subtext.” Characters instead leave the reader to fill in the blanks of what’s not being said, and Terao’s choice to avoid dialogue markers leads to the feeling that each protagonist belongs to a single suffering conscience—even as they pit themselves against each other amidst the rat race of the tech industry. One person’s suffering blends seamlessly into another person’s longing, shame, and desperation, even as characters grow as estranged from each other as they do from themselves.

Eye of the Monkey by Krisztina Tóth, translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet, Seven Stories Press, 2025

Review by Eva Dunsky

Krisztina Tóth slowly unfolds an affair between a psychiatrist and his patient in Eye of the Monkey, but it’s the societal backdrop to that affair that ultimately commands the reader’s attention. Glimpsed fleetingly in brief details as characters transit from one place to another, the world of the Hungarian writer’s latest novel gradually reveals itself as one at the tail-end of horrific, unspecified national tragedy.

The novel begins in Dr. Kreutzer’s office as Gisella, his new talk therapy patient, discusses her mundane life. A married and childless professor at the New University, she goes to work each morning and comes home to food on the table, which is acknowledged as a privilege in this world. Despite being severely restricted in what the university permits her to teach (they promulgate a strict curriculum and professors are shills for the government), she gets along fine—until a young man who claims to be her son begins following her around. She insists that she’s never been pregnant. With Dr. Kreutzer’s help, Gisella starts unpacking her family history, but is stymied by the impossibility of full honesty in a totalitarian state. She’s locked out of her own memory, and as she begins to excavate her turbulent childhood and the recollections of the older sister she never really knew, it becomes increasingly clear that Dr. Kreutzer has his own motives.

As they continue their doctor-patient relationship together in tandem with a romantic affair, the mystery of the young man’s parentage is quickly subsumed into the novel’s general atmosphere of mysterious omission: What has happened in this near-future autocracy, where the gap between rich and poor is so extreme that the indigent are relegated to increasingly ungovernable segregated zones? Where even the relatively well-off are subjected to mass surveillance? Where the government, referred to as the United Regency, has its tendrils in every aspect of citizens’ lives? If you’re thinking that this sounds eerily familiar, you’re not alone; “I love how it speaks to our current moment,” says translator Ottilie Mulzet. “Not just in Hungary, not just in the United States, but in so many places. Tóth writes about the daily lives of the people affected by these hybrid regimes in such visceral and yet compassionate detail.”

Despite the novel’s intentional vagaries and gaps, the writing and translation are gorgeous and specific; a lightning strike is described as “. . . stringing this curled up human pearl onto its incandescent thread.” Even though the novel is written in close third and the characters are unable to speak openly with each other (or even introspectively) due to their fear of surveillance, the richness of the prose opens up a rich and engaging vision into their lives.

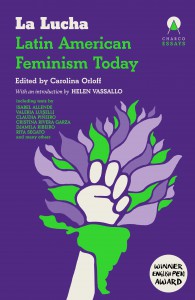

La Lucha: Latin American Feminism Today, edited by Carolina Orloff, Charco Press, 2025

Review by Eva Dunsky

In La Lucha: Latin American Feminisms, a broad and varied cohort of feminist authors and translators work together to “. . . reorient the script, to deepen and widen the lenses through which feminist action—both everyday and revolutionary, intimate and historical—is understood and enacted.” The book is divided into three parts: “La Lucha is Intersectional,” which focuses on the perils and potentials of coalition building across an incredibly diverse region; “La Lucha is Territorial,” which homes in on land rights and the intersection of feminist and ecological activism; and “La Lucha is Personal,” which offers narrative-driven accounts of individual women and their feminist awakenings.

The first section sees its authors trying to tease apart the factors that lead to either feminism or its opposing worldviews. Yásnaya Elena A. Gil draws from the work of Kaqchikel writer Aura Cumes in her chapter on Indigenous women and nation states, stating: “. . . colonisation cannot be explained without patriarchal oppression . . . conditions of gender are created not only in response to Western oppression but also to a colonial system with established power relations . . . For Cumes, these colonial relationships to white women are frequently expressed within feminist organisations where relationships with Indigenous women are not always horizontal.” Considering the systems of colonial domination in Latin America is crucial, and what’s innovative about this section is its insistence on exploring how this phenomena has never been a thing of the past, but rather a dynamic force in contemporary feminist organization. The first step toward a true ethics of feminism, they imply, must be a recognition that my feminism isn’t always your feminism—even if that truth is uncomfortable and feels dangerous.

As a White woman from the West, from the seat of power that sewed chaos in the region and led to many of the unequal conditions described, my reading experience spanned both recognition (as a staunch feminist myself) and wonder; how am I challenging and/or reaffirming the power dynamics described?

What binds these essays together is a concern of how feminism intersects with other forms of social justice—ecological, political, territorial, and personal. With each essay, the definition of feminism and its attendant complications deepens and takes on new valences, which was an explicit aim of editor Carolina Orloff. As she writes in her introduction, “The aim is not to discard European or Anglo feminisms, but to decentre them. . . . In so doing, [La Lucha] rejects the quiet violence of absence and the polished coherence of singular narratives.”

Single narratives, these authors imply, are an existential threat—one that leads time and again to strains of thinking that result in ecological disasters, gender-based acts of violence, and technocratic world orders that we simply can’t afford. Feminism, it’s implied, can be an answer and a sort of balm, provided it remains as diverse and complex as the experiences of women themselves. As Isabel Allende writes in her chapter: “Feminism is not about replicating the disaster. It’s about mending it.”

Timothy Berge is a librarian living in Richmond, Virginia.

Eva Dunsky is a writer, teacher, and translator. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Joyland, The Los Angeles Review, The Rumpus, Bookforum, and Pigeon Pages, among others, and she’s at work on a novel. Read more of her writing here.

Regan Mies is a writer and translator in New York. Her work has appeared in the LA Review of Books, Cleveland Review of Books, Necessary Fiction, and elsewhere.

Sofija Popovska is a writer, translator, and Editor-at-Large at Asymptote Journal. Her other work can be found in Circumference Magazine, mercuryfirs, Farewell Transmission, and in the upcoming Issue 12 of FU Review Berlin, among others.

Liliana Torpey is a writer and translator from Oakland, CA. Her work has appeared in The Rumpus, NACLA, and Euronews Culture. She is currently pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at San Francisco State University.

Mandy-Suzanne Wong writes experimental fiction, essays, and poetry. Her books include The Box and Daughter of Mother-of-Pearl, both published by Graywolf Press.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: