This month, we’re introducing thirteen new publications from eleven different countries. A strange and visceral collection of poems that distort and reimagine the body; a contemporary, perambulating study of the contemporary city; a novel that forsakes linearity for a complex exploration of chance and coincidence; a series that splits the act of storytelling—and the storyteller—into kaleidoscopic puzzle-pieces; an intimate and unflinching look at motherhood and its disappearance of boundaries; and more. . .

Transparencies by Maria Borio, translated from the Italian by Danielle Pieratti, World Poetry Books, 2025

Review by Jason Gordy Walker

Italian poet Maria Borio’s English debut, Transparencies, transports us to an Italy defined as much by glass, screens, and holograms as it is by history and landscape. Divided into three sections—“Distances,” “Videos, Fables,” and “Transparence”—Borio presents a world where past, present, and future converge toward an audible silence, where the self presents itself as genderless, morphable—the I becomes you becomes we becomes they—and the poet plays not a character nor a confessionalist but an airy, elegant observer, as illustrated in “Letter, 00:00 AM”:

At the end of the video, soundless voices,

hollowed-out faces scroll like the ground stumps

of legend: even people with desiresemptied like furrows in tar can carry

a fable. The screams are timbers, old water

they turn to bark, white knots, even.

Danielle Pieratti’s translations preserve the glassiness inherent in the Italian originals; she has strived for accuracy of voice and image, as evident in “Green and Scarlet” (“Verde e rosa”), an eight-part poem that considers natural, national, and human borders: “Between the trees there’s the border’s furrow / the heavy sign that stopped them / all around shapes spring up like nations.” In an interview at Words Without Borders, Borio recalls how she and Pieratti chose to use “scarlet” instead of “pink” when translating “rosa”: “ . . . in English it’s literally ‘pink,’ but . . . the color referred to the luminous atmosphere of a sunset in the woods, so ‘pink’ would have given too sharp an impression . . . Danielle came up with the word ‘scarlet,’ which . . . feels softer, more delicate, with a gradual outpouring . . . .” Such close attention to diction permeates the collection.

Although the book examines the modern world and its technology—recordings, photos, videos, cellphones—Borio refuses to be glitzy (she’s no Twitter-verse poet). Describing the London Aquatic Centre, she pens lines like, “The transparent organs overhead open / become a soft line chasing itself, / cleansing the breath’s dark colors . . .” and “Life is everywhere, in the curved line / we inhabit as though thinking.” Simultaneously detailed and abstract, her verse brings to mind Eugenio Montale and Wallace Stevens, two influences that Pieratti mentions in her illuminating translator’s note—although there’s some European surrealism rolling through her veins, too: “The cactus spines clench their vertebra of water.” Such accents only add to her poetry’s dreamlike magnetism, its cultured mystique.

Borio’s original Trasparenza, published in 2019, contains over twice the amount of pieces in this new edition, but Pieratti has selected poems that feel “most resonant with the unimaginable events of the subsequent four years.” Now, in 2025, with totalitarianism run amok, they feel more relevant than ever. Occasionally spanning across the page with an awareness of landscape (“In the sharp pane of dawn the train’s blade is an aerial view.”) or surprising us with brilliant enjambments (“The sky presses down on everyone, bodies / slide from shirts.”), the poems are always concerned with atmosphere—with interpreting our surroundings: “The houses on the water will stand firm / but the eyes around them aren’t human. // Atmosphere to atmosphere everything transforms.” They have a floating quality to them, but the voice feels trustworthy, unpretentious, and rational in its otherworldliness. These Transparencies might be just as limpid as the collection’s title, but still they retain their own mysterious inner core. That is just one reason why I’ll continue to return to this book, as our collective future transforms into our past.

Natalja’s Stories by Inger Christensen, translated from the Danish by Denise Newman, New Directions, 2025

Review by Fani Avramopoulou

Inger Christensen, a Danish writer associated with the systematic poetry movement, is known for her use of form as influenced by mathematics, an innovative approach clearly present in Natalja’s Stories. A novel in stories, the work was originally written in Danish in 1988 as Christensen’s contribution to “Septemberfortællinger,” a project conceptualized by Vagn Lundbye and inspired by Boccaccio’s Decameron, in which a framing story provides an armature for a hundred stories told by ten different narrators. Lundbye’s framing story kicked off the project with the premise of a catastrophic event that forces a group of people into isolation. With this as their starting point, seven other writers (including Christensen) were tasked with writing seven stories each to bring Lundbye’s frame to life.

Natalja’s Stories, at last translated into English by Denise Newman, tells the life of the narrator’s grandmother, Natalja Valadon. This starts out as a familiar construct: a grandmother speaks and a grandchild listens, absorbing the tale into her own familial identity, later repeating it as her own. However, it doesn’t take long for it to become clear that Natalja’s story is not a simple oral history. Pronouns soon become unsettled, and Natalja begins predicting her granddaughter’s future while simultaneously sharing details of her own past. By the end of the book, the story of who Natalja is—and isn’t—becomes a shifting mosaic of plotlines that by turns contradict, expound upon, and eclipse one another.

The book opens with Natalja’s journey from Crimea to return her mother’s ashes to her native Copenhagen, and an accident during this trip is among the many scenes that get repeated across the seven stories, with small embellishments and alterations each time. As the train suddenly jolts, the narrator—who may or may not be the “real” Natalja—is:

flung into the air, where it felt like she was floating for an eternity before falling and striking her head on something hard. But during that eternity, she thought that she was on her way down into a tall fern from the past where a black snail was signaling for help with its antennae until the paramedics came.

After being struck unconscious, Natalja eventually wakes up in a room with seven people she has never met. She has no idea where she is, and the details of her own identity escape her. If asked to locate Natalja’s Stories in time and space, I might find it in this moment of suspended dislocation.

It’s not easy to confuse readers in a way that also delights them, but Natalja’s Stories accomplishes this handily, unfolding like a geometric puzzle. Natalja is a grandmother, a granddaughter, and an imposter among imposters. She might even be a cat, aptly named Mirage. Her story is one that can only be told in the plural, because it is a story of constant reinvention and addendum. If Vagn Lundbye’s isolating catastrophe is anywhere in Natalja’s Stories, it may be the train crash (which may or may not have happened), or it may be lingering in the background as an implicit awareness that life can change in the blink of an eye. The characters in Natalja’s Stories—whoever they are—shake this truth open to reveal within it a space of radical possibility. They change their identities, rob their masters, lie about their pasts, and leave home with nothing but a few gold coins for lives of continuous arrival.

The Remembered Soldier by Anjet Daanje, translated from Dutch by David McKay, New Vessel Press, 2024

Review by Nichole Gleisner

Anjet Daanje’s The Remembered Soldier is set in 1920s Belgium amid the aftermath of the Great War, and from the first sentence of this sweeping novel, a note of deep uncertainty is tolled: “Maybe this is the last time he will walk down the familiar corridor as the man called Noon Merckem. . .”

His name is an invented one; the individual in question was found at noon, wandering naked near the town of Merckem with no memories—an enviable state when compared to his fellow former soldiers in the asylum who are tortured by PTSD, but still disconcerting. What is it like to go through life without any sense of what one has endured? The novel’s title, with the uneasy addition of the past tense, underscores memory’s vagaries and reveals a primary preoccupation: the inconsistency and fallibility of our ability to remember the past, especially one warped by extreme trauma.

Noon is called out of the safe routine of his memoryless existence when a woman named Julienne claims him as her husband. Against medical advice, he is soon rechristened Amand Coppens, and returns home. There, he finds two young children who greet him cautiously, and a backlog of bills accumulated during the five years since the war’s end. In Julienne, one can detect the simmer of desperation that war widows must have contended with—although she also capitalizes on the massive societal mourning that marked these years by offering kitsch photography sessions of battleground scenes. Against his judgment, Noon/Amand is drafted into posing in uniform with grieving widows seeking solace, lulling them with the seductive story of his miraculous return. Through such careful descriptions of the photographic process, Daanje calls into question the process of commemoration itself and how memories are staged.

The novel progresses slowly, with the buildup of winding sentences that deposit just-recalled snippets of memory. As Noon/Armand wades through daily life, penetrated with intermittent flashbacks, the reader must parse through these thick layers of sediment. In David McKay’s rendering, the sentences can feel necessarily tedious, such as in a moment when Amand grapples with the fleeting nature of his memories while dancing one evening:

But he holds her tight and their legs keep time effortlessly, and the music washes through his mind like rain through a parched forest and then the sun comes out, and the look in her eyes is no longer so wary, she gives herself over to him with a child’s naïve trust and her body is warm and supple, and he’s forgotten that he will forget her and it doesn’t matter anyway, this moment is all that exists.

As life with Julienne unleashes more memories for Amand, The Remembered Soldier builds in intensity. Fitful, barely sleeping, afraid of episodic periods of violence that have complicated his home life, Amand—and Julienne—must both ultimately choose how much to remember and how much to forget, a domestically-scaled confrontation that mirrors the pervasive questions postwar societies must reckon with: how can soldiers reintegrate into society after having seen and committed atrocious acts? How much can we allow ourselves to forget? To forgive?”

The Deserters by Mathias Énard, translated from the French by Charlotte Mandell, New Directions, 2025

Review by Regan Mies

On the Havel River, near Berlin, a small ship is hosting an academic conference in the memory of Paul Heudeber, the mathematician and author of The Buchenwald Conjectures—a renowned work of mathematical theory, poetry, and commentary on life in the titular concentration camp. In attendance are his daughter, the math historian Irina Heudeber; her mother and Paul’s partner Maja, a once-prominent socialist activist; and a cast of graduate students and academics at the top of their fields.

Elsewhere in time and space, a man is fleeing an unnamed war on a parched hillside, not far from the Mediterranean. Gunfire hammers from just beyond sight as he makes his way toward a family cabin, recalled from his haziest memories. There, his anticipated solitude is broken by an encounter with a woman and her donkey.

As in all of Prix Goncourt-winner Mathias Énard’s works, The Deserters marries captivating historical detail with nontraditional structure. (His 2008 novel, Zone, was composed of a single, five-hundred-page sentence.) Here, the novel’s two narratives quickly branch out into varying perspectives, points in time, and forms. When the second day of the Heudeber conference coincides with the New York terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, film clips from the city run concurrently on the news, and Irina notices how, as the hours pass, more and more perspectives of the Towers must be being sourced from more and more cameras across the city. So, too, does the novel begin accumulating perspectives on her parents’ lives—through excerpts from Paul’s work, his archive of correspondence, a biography, a letter from Maja’s lover, and so on. The perspectives of the soldier’s narrative also begin to shift, swinging between him and the stranger he meets.

Much of The Deserters’ allure is its language—in a virtuosic translation by Charlotte Mandell—but equally compelling is the challenge the novel presents; one can’t help oneself from trying to decipher the relationship between the two plotlines, wondering what revelation from one story shines light on the other. As each plays out in parallel, these narratives confront the reader with the vastness of human experience—but reading farther is to watch this complexity give way to profound, eternal simplicity. A chance encounter. A conjecture proven correct. However disparate their circumstances, all of Énard’s characters face the natural world, the nature of war, the fact of suffering. They consider legacy, intimacy, forgiveness. As Irina listens to her aging mother speak, realizing the nearness of death, she narrates, “The present was swaying, from one foot to the other, like someone hearing alluring music and wondering whether to dance. All the threads of History seemed gathered together in a single hand.”

Deep Breath by Rita Halász, translated from the Hungarian by Kris Herbert, Catapult, 2025

Review by Regan Mies

Language is at the heart of Hungarian writer Rita Halász’s Margó Prize-winning debut, Deep Breath. In following Vera, who departs with her two children after a series of increasingly violent outbursts from her husband Péter, the novel continually returns to the intricacy and rhythm of words—as well as how they transform in the possession of different owners.

Krist Herbert’s intricate translation work is on display already in the novel’s first pages, as Péter’s voice rings through Vera’s mind: “Either the snow is falling, or it’s snowing, only hicks say it’s coming down.” Moments later, their daughter echoes his voice, his words, while correcting her younger sister: “The snow isn’t coming down, it’s falling.” Then, in Vera’s narration during a following scene, the snow is again “coming down.” For a moment, she reclaims the phrase—only to reject it once more; when Péter reaches out for a first meeting after the separation, Vera thinks, “We could start over. Maybe it would be better,” and remarks: “The snow is coming down again. It’s falling still sounds prettier.”

In such deft layers, Halász uses vocabulary to clues readers into Vera’s state of mind regarding her relationship, while subtly giving piecemeal indications into the relationship itself. At one point, Vera almost offhandedly narrates a friend’s beat of advice: “You should take photos of your neck.” Step by step, scene by scene, the novel thereby builds toward clarity—what happened to whom and when and how—while also tracing a progression toward Vera’s ownership over her own words, her perspective of events, her identity.

When she eventually meets Petér at a café, Vera speaks in phrases that don’t meet her abuser’s approval. She says “mm-hmm,” thinking to herself, “I’m sure he’s furious that I said mm-hmm. It’s not mm-hmm, it’s yes.” At couple’s counseling: “Péter doesn’t like when I use the word pregnant. . . . A child is God’s gift. It’s something a woman is expecting. I could have corrected myself . . . but instead I just say that I was pregnant.” By so sharply tracing the contours of Vera’s relationship—and her eventual liberation from it—Halász turns language into a mirror, demonstrating how words can reflect back things we may not yet know about ourselves.

The City and the World by Gregor Hens, translated from the German by Jen Calleja, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2025

Review by Michelle Chan Schmidt

The City and the World is Gregor Hens’s nonfiction perambulation through the art, literature, and memories that re-imagine urbanity, a whirlwind world tour of metropolises both new and old. Translated with Jen Calleja’s ease and control in her second collaboration with the author, the book follows near-literally in the footsteps of classical flâneurs like Walter Benjamin and Michel de Certeau—as well as the more recent feminist texts of Lauren Elkin and Valeria Luiselli.

Though The City and the World centers its narrative through Cologne (where Hens was born), Berlin, Paris, London, and New York in a canonical exploration of Euro-America, Hens’s text gleams most brightly when it ventures into the supermodern lights beyond the Occident. Especially striking are the images that counterpoint the text, such as the works from Rebecca Ann Tess’s “Alpha++ Models” series, which occupy seven double-page spreads with surreally scaled photographs of Shenzhen, Hong Kong, and Dubai. Yet, for a text that purports to deal with the world, even proclaiming that “it is primarily men through whom the history of flânerie is usually told,” the generous reading list that concludes the essay still anchors itself within masculine Eurocentric modernism, featuring Marc Augé, Michel Foucault, and W. G. Sebald. Whose world is it?

Hens excels in texturizing the palimpsests and layers that accrue to form an urbanity; so a city is not only the “façades and plinths, streets and tank corridors that practically come out of nowhere and lead off into yet more nothingness,” but also the psychogeographic movement, the “country [and] river,” that “play into each other, determine each other and merge with each other.” Most powerfully, Hens asserts that “even the city as a whole, when viewed from a plane or from satellites, is art,” a lived art created by the individuals that both constitute its make-up and construct its “complex structure of countless aesthetic moments,” practicing their daily lives in tendered relations with “commercial interests.” Shadowing this conceptualisation are utopian cities like Constant Nieuwenhuys’ New Babylon, a space of anti-capitalist play imagined from 1956 to 1974.

In Calleja’s intelligent, capacious voice, Hens’s discerning study of historical urbanism marks the boundaries of the present. “When the city is dug up in a thousand or ten thousand years,” they write, “. . . when the Strip, the Las Vegas casino corridor, is all that remains of our civilization—what will the archaeologists of the future discover about us?” But cities are countless variations of form and history in flux, and the Las Vegas Strip is far from the only mode of urbanity, even as it “quotes and co-opts and exceeds all other” cities “with its Eiffel Tower” replica. Despite his evocations of Shenzhen and Hong Kong, Hens fails to note the People’s Republic of China’s plan to unify the Pearl River Delta in southern China into a “Greater Bay Area,” which would generate a megalopolis of eighty-six million people and portends the urban structures of the future. How would Hens read the megalopolis? How does the art of the city shift through political and technological pressure? One imagines, in reading through his wanderings, that the lived city is always proliferating into another form—and, that as utopian imaginations lift off the ground, the text renews the world.

Sleep Phase by Mohammed Kheir, translated from the Arabic by Robin Moger, Two Lines Press, 2025

Review by Regan Mies

In Mohamed Kheir’s Sleep Phase, a man is detained and imprisoned without explanation. Seven years then pass before Warif is released into a Cairo that has since become unrecognizable; the small shops he remembers—where you could find lightbulbs or spices—have become skyscrapers and chain restaurants; old market carts and fruit vendors along the Nile riverbank have transformed into smooth benches, seating clusters of foreigners. Warif tells himself, “It wasn’t that the names of the streets and squares had changed . . . it was that the streets and squares themselves were different and now seemed estranged from those names.”

Warif, too, is estranged—from his city, from his past. His parents had passed away during his incarceration, fundamentally shifting his world. In an attempt to resituate himself, the first task Warif sets on is to get his job back, as a translator between the state and the tourism industry. From there on, Sleep Phase unfurls into a Kafkaesque account of blurry English-speaking bureaucrats with unplaceable accents in vast, echoing public buildings with unlabeled doors. At meeting after meeting, Warif is told that his request is unique but promising, that there are always “just a few hoops to jump through.”

Sally is the one getting Warif into these meetings, a woman who is Egyptian and European, who is sometimes in love with Warif and sometimes not, who belongs to “a world of money, bank accounts, and budgets” as well as art and culture. The two reconnect after Warif’s release, and it’s through Sally, too, that readers begin to understand the Cairo of before: she and Warif first met during “a brief window when everyone could speak their minds,” when Warif felt he could express his views and opinions “for the first and last time in his life.” As past and present surreally converge, Kheir uses his characters’ ever-shifting perception of their surroundings to probe the truths around globalization and its consequences, patriotism and its faults, free speech and its oppression. Simultaneously paralleled on various levels of human intimacy, it is Warif’s disorientation that soon fosters his ability to navigate the questions of who he was before his arrest—and who he still can be.

Lifespan Narratives by Alexander Kluge, translated from the German by Leila Vennewitz and Alexander Booth, Seagull Books, 2025

Review by Regan Mies

In the mid-2010s, German writer and filmmaker Alexander Kluge responded to some lines from Ben Lerner’s poems. A back-and-forth then ensued between the two artists, spanning stories, sonnets, and literary dialogue. In a 2017 Paris Review interview between them, Kluge spoke to his and Lerner’s work: “We deal with moving bodies. Moving reality. And this is something that you cannot present in a linear way, but in the form of constellations.”

Form as constellation is an idea that stretches back to Kluge’s earliest work; his myriad, shifting structures are foundational even in his first book, Lifespan Narratives, a collection of stories written between 1958 and 1962. Originally translated by Leila Vennewitz, it is now appearing in a new edition, expanded upon by translator Alexander Booth as well as Kluge. In these ten stories, narratives take leaping, multi-form, and multimedia turns. Reading them gives the sensation of tackling a file cabinet of ephemera, the professional alongside the personal.

“Manfred Schmidt,” for example, opens with a series of short interviews conducted after a post-WWII carnival, in which the speakers include the event’s security, catering, and treasury staff, as well as the police. There’s been a death, but the accounts take a turn away from the drama and veer into the life story of the titular womanizer and air force deserter, M.S. Here, Kluge makes use of diaristic, epistolary passages; a curriculum vitae; and a lover’s monologue. Elsewhere, “E. Schincke” tells the story of a national socialist professor faced with the impending reality of Hitler’s regime, incorporating pages from the narrator’s dream log and an academic paper on the cultural reforms of the Carolingian empire. In the tale of war profiteer “Sergeant Major Hans Peickert,” snippets of childhood lullabies appear alongside business reports.

Kluge’s interdisciplinary corpus can also be gleaned from this edition. “Anita G.,” a story centered around one woman’s post-war desperation, moves between the short scenes of an affair, the daily routine of a defense attorney, bursts of screenplay-like description, and an eventual cross-country run from the police. In 1966, Kluge turned the story into the Silver Lion-winning film Yesterday Girl, and in Lifespan Narratives, the text opens with stills from the film.

The years before, during, and directly after World War II were far from straightforward, and the attempt to document the truth of these periods demands something other than simple narration. Through constellations of fiction and reality, Kluge renders hope, horror, fear, guilt, and, sometimes—just barely—tenderness. The feeling left with readers is rightfully grim, on every scale. In “Anita G.,” Anita steals a final glance at a partner, and unfeelingly thinks, “So this was all that love accomplished.” In “Lieutenant Boulanger,” which reads like a court case or magazine exposé, a young man must manage “cranium collections” at the camps, realizing quickly that “there is no such thing as good intentions,” admitting that they must be “beside the point.”

Motherhood and Its Ghosts by Iman Mersal, translated from the Arabic by Robin Moger, Transit Books, 2025

Review by Xiao Yue Shan

When one of my closest friends became a mother, speaking with her made me suspect that I was somehow experiencing emotions on a paler spectrum, for the way she spoke of affection, intimacy, fear, sadness, and guilt was so intensified, so in tune with the core of her, so visceral and unfathomable. It made me think that motherhood is up there beside love and war on the list of humanity’s perennial themes; despite not being a universal experience, each of us are marked by it, indelibly and idiosyncratically, and the extremities and vacillations revealed by its testimony are essential in defining the basic matter of our social existence: attachment.

For those who live the subject, it takes a certain bravery to write these works, for there is no figure more judged than a mother. Iman Mersal’s Motherhood and Its Ghosts must then firstly be admired as an object of courage; it is a shockingly revelatory piece of self. Despite opening—as many such texts do—with a comparative study of mothering, parsed against other findings and records, Mersal ultimately turns away from the stoic confessions and archival tracks, abandons the references and attempts at objective thinking, delving instead inward. About halfway through, the book gives way to a series of journal entries, and as the hinge swings close on the first—more analytical, more investigative—sections, a more audacious document takes place, and through it the strange unbearability of motherhood can be seen.

There is an impossibility of situating motherhood within the constructs of individual experience, because it is an experience of duality—of actual, bodily division and multiplication. A certain unity remains between mother and child even after the cut of the umbilical cord; relating a conversation between her and her son, Mersal describes a confusion stemming from this blurred line: “when . . . I was with him in the dream then I was really with him, and it was only natural that I should remember what had happened to us there.” As a state of fluid realities, motherhood is unbearable because it only exists in the fact of one’s children, who cannot help but become increasingly more autonomous and unknowable—and as the distance grows between the two bodies, the diffuseness, fragility, and helplessness of identity is revealed. It is to be pulled in different directions, and the part of yourself that you recognize can only sit at the center of everything, forever gathering in the various threads.

It is fitting then, that photography and portraiture is something Mersal continually returns to. Speaking on her own mother, who died still young, she writes: “She requires a journey inside, a journey to save her from becoming a ghost or a silhouette, to save her from the absence that is the proposition of every image.” When we look at the image of a loved one, it is their mystery that first confronts us; we do not know what they are thinking, what they are feeling, we can only imagine or hallucinate the context, but our love demands that we revive their discernible, unapproachable figure inside of us. It is the simultaneity of the familiar and the utterly impenetrable—and therein a small semblance of what it must feel like to look upon the face of your child.

Mersal’s poetic habits are at the forefront throughout, with the economy of verse lending the prose a tranquility and steadiness—while still radiating the aura of an emotion so powerful it can only be familial. Robin Moger’s translation is measured, knowing, willing to follow the author’s shifting registers as she rises and falls into dreams, illusions, wanderings, and admissions. Yet, the most poignant aspect of Motherhood and Its Ghosts is not what’s on the page, but the intimation of an invisible text, one that cannot be articulated because it is too big for human speech. Even while tracing over the common representations and facsimiles of motherhood, Mersal is still gesturing towards the expanses that it awakens. Enormities of love, agony, regret, hope. The words don’t seek to describe them, but simply show us where they live.

Phantom Limbs by Lee Min-ha, translated from the Korean by Jein Han, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2025

Review by Nichole Gleisner

Phantom limb pain: initially thought to be a problem inherent to those who’ve undergone amputation, it was later discovered that patients born without limbs can also experience this symptom. In Lee Min-ha’s Phantom Limbs, one may first assume that the suffering described belongs to the uncanny subjects on display: the child dragging an umbilical cord on a tin roof in “The School on the Roof”; or M, “hanging upside down like a fetus” with “two drawers . . . attached to her arms” in “Möbius has Vanished from the Möbius Map.” But delve deeper, and it is made apparent that this pain penetrates to the root of existence, sparing no one.

Originally published in 2005, Phantom Limb is Lee’s debut in both Korean and English, announcing the arrival of a riveting and visceral voice. In an eloquent afterword, Jack Saebyok Jung notes that she had been associated with the Futurists, a group of South Korean poets in the early 2000s, and comparisons could also be made between her work and the European school of the same name—which arose out of the desperate need to respond to the horror unleashed by WWI. These poems brood a habit of violent carnal depictions and are drawn to the darkest aspects of the unconscious, but Lee renders the mundane aspects of daily life as equally horrific: “The / long underground tunnel that swallowed me was crawling aimlessly / without end. I was on the morning commute.”

In Jein Han’s unflinching translation, the language on the page is thick and disturbing. Viscous sounds are common, such as a tendency toward the consonance of –m: both in the phantom limbs of the title and the assonance of “mouths of maidens chewing squid.” The imagery, too, congeals into a glutinous morass: a tree has a “flabby torso.” In another poem: “There is a kitchen that finely grates the women marinated in fog / and kneads them into a dough.” When Lee considers love, she rejects traditionally romantic motifs and embraces the strange, evoking the muse’s “watery mouth” or “onion eyes.”

These poems probe the dark hole of memory, “the mushy flesh of time,” and seek to reconfigure articulations of beauty. In an uncharacteristically straightforward moment, the poet states her intentions in “Talk show—an insistence on relationships,” which can be read as a compelling and dazzling art poétique:

Literature can speak out on everything but in this country its name has been ossified into the platitude that one should not speak out on everything. It is because of this convention that our literature is stifled. Conventions must be destroyed.

Lee’s singular, radical attempt has been artfully captured for a new audience in this significant translation.

Exercises 1950-1960 by Yannis Ritsos, translated from the Greek by Spring Ulmer, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2025

Review by Fani Avramopoulou

Yannis Ritsos rose to prominence in Greece in the late 1930s, after his epic poem “Epitaphios”—an ode to the tobacco workers killed by the authoritarian Greek state during a strike in Thessaloniki—sold close to ten thousand copies within a few days of its release. Not long afterward, the book was burned at the foot of the Acropolis by Ioannis Metaxas’s anti-communist regime.

A member of Greece’s Communist Party (KKE), Ritsos quickly became a favorite poet of the Greek Left. Between 1946 and 1949, during the nation’s Civil War, he was exiled to a prison camp alongside other leftists and communists, where inmates were routinely subjected to torture. In 1967, Ritsos would be imprisoned again under the Papadopoulos regime, and during the window of time between his first release and his second imprisonment, he composed the poems in Exercises 1950-1960. Startling in their simple beauty, these poems refuse to turn away from suffering while simultaneously professing an unshakable love for the world. Spring Ulmer’s translation of them into English fills a critical gap.

The poems in Exercises 1950-1960 are primarily narrative, and while each of them depicts unique scenes with nameless characters, they all seem to inhabit a shared world, tinged with a distinctive surrealist style. The collection is organized by subtle visual shifts, with certain images pushing into the foreground at different points in the book, transporting the reader gently from one scene to the next—thorns, trees, the color white, to name a few. The element of time, on the other hand, evades familiar modes of linear progression. The poems do not follow a clear chronology, and time is frequently a site of transformation: a sick woman multiplies into a group of happy young schoolgirls, wooden doors turn back into the trees from which they were made, and carts pulled by tired horses and men transform into ancient chariots. In “All the Time,” Ritsos writes:

. . . life stood

in front of unshaven time, like the woman stands in front of the man

waiting silently to be kissed and sung to

and then to give birth and sing alone.

The past and the future cannot be disentangled from the present in these poems; they swirl around each other continuously, imbuing the collection with timeless wisdom and hope.

Ritsos’s hope for the future feels revelatory in this cynical moment, but in always tracing back to the collective, it is also convincing. In “Suppressed Thirst,” a thirsty man finds relief in the knowledge that someone, one day, will have a drink of water at his table, even if the man himself is no longer there. The imagined stranger’s relief thereby becomes a source of contentment. Elsewhere, the wellbeing of strangers is something to fight for or to protect. In “Evening,” two women walk up a mountain in a strong wind, and one of them, holding a lamp that keeps getting blown out, speaks to the other woman: “Put your hand, she said / in front of that star, so the wind won’t blow it out. It’s not just for you.” In their artful rendering of small, quotidian moments, the poems in Exercises 1950-1960 embody this protective gesture, offering the metaphorical star to us, the readers. Pain and beauty cohabitate in these poems, but there is always a future to work toward, and everything is always for everyone.

Tamangur by Leta Semadeni, translated from the German by Tess Lewis, Seagull Books, 2025

Review by Nichole Gleisner

Leta Semadeni’s oneiric Tamangur takes its name from an actual place—an ancient pine forest in Switzerland near the country’s eastern border, and a mythical realm where the dead are said to go. This simultaneity of reality and imagination permeates the text: they are offered as two equal possibilities, two ways of understanding the world.

Narrated from the perspective of a young girl whose grandfather has recently taken this final journey and thrumming with poetic imagery, Tamangur probes the line between myth and truth. An eclectic cast of characters populate the child’s daily life: Grandmother, eccentric Elsa, Chan the dog, a crocodile-eyed seamstress, but also ghosts and other personified creatures. “When the days grow dark, it gets tight in the village,” Grandmother says. “In those moments, memory lounges here and there like a sleeping animal and blocks the way.”

Memories of Grandfather—whose departure is deeply felt—offer levity and gestures of kindness, as well as providing glimpses into the passionate love shared between him and Grandmother. These moments are recounted in passing asides of spied intimacy, gathered like glinting bits of gold, and mark a notable contrast from the darker, more troubling recurrent memories of the child’s parents and young brother. The translation by Tess Lewis highlights these tensions, capturing necessarily the slight disturbances in the language, or allowing moments of strangeness that feel convincing for the voice of the young narrator: “Light from the streetlamp flickers through the fitful gap between the curtains and falls onto Grandmother’s face, which looks like she has slipped out from behind it.”

Organized into eighty-four vignettes, the novel evokes the way memories surface, moving languidly from one scene to the next, though not in any particular order. Abandoning traditional narrative structure, Semadeni instead opts for a stream-of-consciousness, cultivating a dreamy atmosphere of remembrance that diffuses the present. The reader may encounter Grandfather hearty and booming in one chapter, then be taken to snapshots from Grandmother’s earlier life as an intrepid traveler, conveyed in vivid details; for instance, recalling an encounter with Slimane Houali, an animal sculptor from Paris’s Place de la Bastille, she describes how Houali’s “ears shone pink in the backlight.”

Both the movements of Tamangur and the child thrive on Grandmother’s resolute strength, her understanding that: “There are certain rules you have to follow or you’ll end up adrift.” Yet despite her capable nature, Grandmother also possesses an epicurean flair, a full-throated laugh, an embrace of the sensual. She understands the restorative functions of a love affair or a sumptuous meal: “When Grandmother eats, her eyes gleam.” These pockets of complexity make for an absorbing read as we find ourselves wondering along with the narrator: “What vault is darker than the heart?”

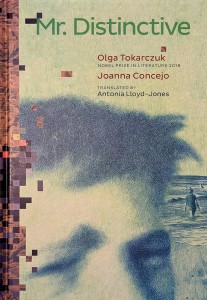

Mr. Distinctive by Olga Tokarczuk and Joanna Concejo, translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, Seven Stories Press, 2025

Review by Fani Avramopoulou

I’d picked up Mr. Distinctive—a collaboration between writer Olga Tokarczuk and illustrator Joanna Concejo—as I’ve enjoyed a couple of the Polish author’s previous books, being drawn to her “constellation” approach to the novel. This latest work did not disappoint; part social commentary, part fable, Tokarczuk’s evocative text here is nestled between Concejo’s charged illustrations.

On its surface, Mr. Distinctive shares little with Tokarczuk’s other books—though it is a terrific follow-up to The Lost Soul, her first collaboration with Concejo. Drawing power from the medium, the union of text and image pushes beyond what we might expect from an illustrated narrative, questioning what it means to “read” a work of literature—as opposed to, for example, a social media feed. Most of Concejo’s illustrations appear to be sketches of photographs, lending an uncanny, dream-like quality to the book as a whole; stacked on top of one another, they are reminiscent of a cinematic montage, but also of scrolling an infinite page or of flipping through an old family photo album. Many of the images feature a particular young boy, and later a man, offering an intimate portrait of a life—at times, reading this book feels like looking through a stranger’s camera roll. Dominating the first half of the book, these illustrations gesture toward the graphic novel and documentary genres without ever fully stepping into their conventions.

Mr. Distinctive‘s images establish the book’s pervasive nostalgia, but at the same time, they feel utterly contemporary. This tension carries into Tokarczuk’s words, translated into English by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, which reveal themselves quietly, almost hesitantly. After many illustrated pages, we arrive at a gatefold concealed by a pixelated close-up of a pair of eyes, which, once unfolded, reveals the story of the titular Mr. Distinctive, a man infatuated with his own appearance and desperate to preserve it.

Ringing with truth, Mr. Distinctive is a story of living and aging in the time of digital narcissism. Its titular character is blessed with a face so beautiful that he cannot stop photographing himself, his self-concept eclipsed by the omnipresent gaze of his public audience. However, when he one day discovers that his face is beginning to blur as a consequence of being photographed too many times, he sets out to correct the problem—and ends up facing chilling consequences. Though the story is speculative in nature, the world it exists in feels close to our own, where the uniform beauty of “Instagram face” is more seductive and accessible than ever thanks to tools like digital filters and the rapidly expanding accessibility of cosmetic procedures. In this, Mr. Distinctive reads like a lingering bad dream; one may feel relieved upon waking, but as the day wears on, reality’s resemblance to the nightmare becomes increasingly uncanny.

This work is an unmistakable allegory, asking readers to examine the way we interact with social media as both producers and consumers of its content—and if this were not enough, the book is also a truly beautiful object. I loved flipping through its pages and opening the gatefolds, and I loved sharing it, hand-to-hand, with friends. Mr. Distinctive requires tactile engagement, resisting the digital world that it takes as its subject and demanding the reader’s presence and intention, its contents revealing itself only through our touch.

Fani Avramopoulou is a writer living in Philadelphia with roots in Baltimore and Athens, Greece. She is an outreach editor at Essay Press.

Michelle Chan Schmidt (she/her) is Asymptote’s Senior Assistant Editor for fiction and a 2023 Editorial Fellow at Full Stop, where she curated the Winter 2024 special issue on “Literary Dis(-)appearances in (Post)colonial Cities.” She has contributed to The Cleveland Review of Books, Interpret Magazine, La Piccioletta Barca, Public Books, and others. She is the 2025 ALTA Emerging Translator mentee for Poetry from Hong Kong.

Nichole Gleisner is a writer and translator and teaches in the French Department at Yale University.

Regan Mies is a writer and translator in New York. Her work has appeared in the LA Review of Books, Cleveland Review of Books, Necessary Fiction, and elsewhere.

Jason Gordy Walker is a poet, translator, and prose writer. His translations of poems from the Norwegian of Rune Christiansen are forthcoming at B O D Y (Czech Republic) and Cordite Poetry Review (Australia). Walker was the February 2025 Artist-in-Residence at Newnan ArtRez in Georgia, U.S.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet, writer, editor, and translator.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: