I am beginning to write in our language,

but it is difficult.Only the elders speak our words,

and they are forgetting.

So begins “C’etsesen” (“The Poet”), written in Ahtna, an indigenous language of Alaska, by John Elvis Smercer. In 1980, there were about one hundred and twenty speakers of Ahtna. At the time of this poem’s publication in 2011, there were about twenty. Today only about a dozen fluent speakers remain. Smercer’s lines reveal his urgent concern with the disappearance of his language and the weight of his task in preventing the language from slipping away. It is a race against time, between generations, for the young to learn the language before the old leave, taking the words with them.

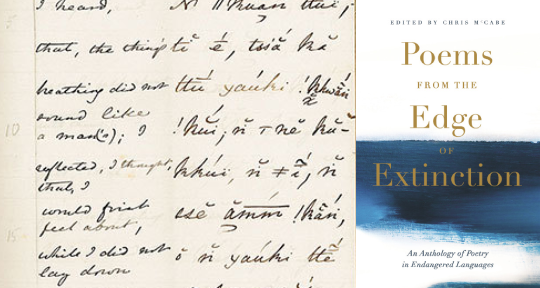

Chris McCabe, editor of the anthology Poems From the Edge of Extinction, has equally set out on such a task: to collect, record, and preserve poems from multiple endangered languages. The anthology grew out of the Endangered Poetry Project, launched at the National Library, at London’s Southbank Centre, in 2017. The project seeks submissions from the public of any poem in an endangered language in order to build an archive and record of these poems for future generations. Of the world’s seven thousand spoken languages, over half are endangered. By the end of this century, experts estimate that these will have disappeared, with no living speakers remaining. Language activism has been growing since the early 2000s, and the United Nations declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages (IYIL 2019) to raise global awareness of the consequences of the endangerment of indigenous languages. McCabe’s anthology, published to coincide with IYIL 2019, contains fifty poems, each in a different endangered language (as identified by UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger), presented in the original alongside an English translation; the result is an urgent and illuminating collection encompassing linguistics, sociology, politics, criticism, and philosophy that, in its totality, represents a manifesto of resistance.

The disappearance of so many languages at such an alarming rate (currently one language is lost every two weeks) is a cause for serious concern. Yet importantly, Poems From the Edge of Extinction doesn’t just center upon these languages under threat, but on their poetry in particular. The decision to create such an anthology provokes many questions: What is the benefit of poetry? What is poetry’s relationship to language? What is the function of poetry in society? When recounting the series of events that led to the anthology’s creation in his introduction, one of the most interesting anecdotes McCabe tells is of searching for information on poetry in Patuá, Macau’s critically endangered patois. Eventually, he contacts Miguel S. Fernandes, a local theatre director and attorney, who tells him, “I’m afraid I’m the only one writing poems in Patuá these days, and I hope I’m wrong.” We’re led to wonder: what does it mean to be the only poet writing in one’s language? And, one might ask, why should it even matter that there is a poet? McCabe argues convincingly for the poetry-preservationist project and cites Australian linguist and endangered language expert Nicholas Evans to make his case: “All too often contemporary linguists turn their back from the bardic threshold, as if these higher forms of speech—through their leap in art, away from the realm of regular abilities like normal speech, which all children simply learn without effort—are no longer a concern of linguistic inquiry.” Not only can poetry document the language before it disappears entirely, it can also inspire resistance and renewed innovation in the language. Poems From the Edge of Extinction is both a rallying call for the continuation of endangered languages, as well as for the endurance, recognition, and necessity of poetry as an art form.

All of the poets in this collection are intensely alert to their struggle, focusing their poems on the changes they are witnessing and on the vulnerability of their language. The first poem in the book “To’a kubari” (“We’ve Stumbled”), written in Bubi (a language of Equatorial Guinea) by Recaredo Silebo Boturu and translated by David Shook, is immediately remindful of the sinister effects on a society when its traditions are forgotten and replaced. Such a shift is represented in the poem’s setting of a solar eclipse. The days’ and nights’ activities are thrown out of joint: “We didn’t do the traditional things / and the guardian spirits left in the lush forest.” The disrupted bond between the Bubi people and their immediate environment shows the natural world suffering: the “aubergine plant dried up” and their “bait rotted”. The poem “ᐃᓄᐃᑦ“(“Inuit”), written in Inuktitut by Norma Dunning, similarly defends its traditions, its Inuit culture, which remains strongly present despite globalisation-generated dichotomies between old ways and new:

[. . .] We are one in two ways.

We live in our Old Ones

Ancientness blankets our young

Whispers of tradition

Are carried by soft winds

From the tundra to city sidewalks

Inuttigut – We the Inuit

We are here

This dual existence is attested to by many of the poets, whose threatened language has been replaced by a more dominant one for political, economical, or environmental reasons. In promoting its work, The Endangered Poetry Project quotes a line from the British poet Ted Hughes: “Poetry is a universal language in which we can all hope to meet.” Part of the strength of this anthology is in demonstrating both the universality of which Hughes speaks and the unique contexts that necessitate our multiple languages. Yes, poetry is universal, and the way in which the poets included in this anthology have rallied for their cause is a testament to this. The poems within this collection all share certain universal themes: love, death, birth, war, aging, nature, family, power, injustice, music. And yet, despite this common bond, each of these poems, through their own language, contains their locality, their inimitability.

In the first story, “Argon,” of his collection The Periodic Table, Primo Levi sets down in writing the unique dialect of Piedmont’s Jews. He says of the dialect: “Its historical interest is meager, since it was never spoken by more than a few thousand people; but its human interest is great, as are all languages on the frontier and in transition.” The story captures the unique force of the dialect and Levi has a distinct purpose in writing this account: “to set [the dialect] down here before it disappears.” Every language contains its own particular grammar and its own vocabulary, formed for its own needs. Each one is a repository for a culture’s identity, history, traditions, memory, and individuals within it: its human interest is great. And poetry has the ability to deploy all of a language, in its entirety. Any tone, register, dialect, inflection can be called upon, even to the point of the inclusion of one individual’s speech, so as to reveal the capability and possibility of the language. Such specificity and inventiveness of a particular language is displayed throughout this anthology.

And it is not only the settings and vocabulary of these poems that are unique, but also the very form of the verse. It is striking how musical the collection is and how the tradition and ritual of such music pervades the poems. “Koonkír Hhandoo” is a traditional song in Goorwa (an Afro-Asiatic language spoken in Babati District in Tanzania) that was transcribed by Andrew Harvey after he heard it sung by Bu’ú Saqwaré. The poem is composed of verses, alternately sung by “singers” and “listeners” in the crowd, while the chorus (“Haya haya hamma hamma,” “yes go on”) is sung by the “listeners.” The title of the poem is a girl’s name, and through the repeated structure and rhythms, she is asked if she is ashamed of the day’s work tasks: preparing manure and collecting swamp-mallows. By singing the poem in unison, as a work song, the group overcomes the hardship of the transition from girlhood into adulthood and celebrates the rhythm of daily life by turning her shame into “a dance.” “Pootyt Crer” (Pootyt’s Chant) was documented by Ian Packer, a Brazilian anthropologist, and was sung by Francisco Pootyt in Krahô, a language spoken by the Krahô people in the state of Tocantins in Brazil. The chant is performed to warm up the speaker and the people during cold nights. The song directly addresses the forefathers who are responsible for the singer being alive and having to now face the suffering of “the night’s Chill.” The importance of the chant being handed down through generations is woven throughout, and the question “but why then / do we hear our forefathers’ chants no more / that standing we used to sing?” is a poignant reflection upon the threats facing the Krahô way of life. The poem ends with the powerful image of energy and fire:

Hêêê

Hêêê

On a firewood

On a firewood

Blaze I am

On the firewood

Blaze I am

The continuation of the song has warmed the crowd and the power of the chant remains unvanquished.

The anthology tracks an interesting relationship between old and young, attending especially to the younger generation’s urgency to resist the loss that will come about with the death of their elders.” Francisco Pootyt is around sixty years old and his chant was transcribed by Ian Packer, rather than being written by Pootyt himself. Pootyt is merely continuing the oral tradition of poetry that is inherent in almost every culture. In “Jesuscrito’is Ja Ñäjktyäj’ya Äj’ Tzumama’is Kyionuksku’y” (“Jesus Never Understood My Grandmother’s Prayer”), Mikeas Sánchez compares herself with her grandmother who “never learned Spanish,” the dominant language of Mexico, but who only spoke Zoque, one of many endangered languages in Mexico. While “Jesus never heard her,” her grandmother “believed that you could only / talk to the wind in Zoque.” The mapping of language with the natural world and local environment is contrasted with language used for wider institutional and political purposes. Within Sánchez, and within the poem itself, these two languages are brought together as she considers the lineage of mother tongues. Martha Fernandez, who writes in Kristang, a Creole language spoken by Eurasians of Portuguese descent, tells not of an inheritance of language but rather a rediscovery. Describing her difficult relationship with the language, she says: “One day I heard that someone/ was introducing you to strangers./ I wanted to be one of the strangers. I wanted to embrace you and say/ “I’m sorry. I should never have let you go.” The younger generation faces a complicated renegotiation of the values of their languages within both a personal and wider political context. Fernandez’s initial shame is converted into acceptance and pride of a language that she has always known and has made her “feel whole again.”

This anthology is a literary and linguistic triumph that has merged art and science, the personal and the political, urgency and perpetuity. Not only is it insightful to read but it is also visually astounding, presenting the written scripts of the fifty original languages of the poems. Championing poets as well as translators, who are given equal credit throughout, Poems From the Edge of Extinction celebrates both individuality and collaboration and, above all, the value of poetry for community. The linguist Leonard Bloomfield defended poetry’s merit in linguistic studies by calling poetry “a blazoned book of language” and this anthology is just such a precious record of the richness of linguistic diversity.

Sarah Moore is a bookseller and editor from Cambridge, UK. She currently lives in Paris and is an Assistant Blog Editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: