Perhaps it goes without saying, but in 2018 translating Indigenous literatures in the Américas from Indigenous languages and/or Spanish is a political act. Even prior to now, at dinner parties and other settings for droll conversation in the United States, people have often perked up when I mention that I study Mesoamerican languages and cultures. With an interest typically grounded in lost civilizations, ancient mysteries, and, occasionally, UFOs, they usually then follow up with an inquiry as to why, if I study dead languages, I didn’t opt to study Latin, ancient Greek, or Biblical Hebrew instead. When I assert that no, Maya languages such as Yucatec and Tsotsil are far from dead, many people refuse to believe it and are more than happy to contest the point.

Of course, the academy is not without its own long-established racism towards Indigenous peoples. For example, when I was in graduate school one professor initially declined to let me pursue Indigenous literatures as an area of transnational study given that, as there is no Maya nation-state there are in turn no Maya national literatures, meaning that a “Maya literature” simply did not exist. If I really wanted to write about Maya literatures, I was told, I’d better think about switching to Anthropology. Another professor rather scornfully told me my employment prospects were nil since there was no such thing as a “Maya Department.” While none of these people denied the very existence of Indigenous peoples, cultures, and languages, through these and other interactions I was repeatedly warned that these were not the province of serious literary scholarship.

So, when I say that translating literature from Indigenous languages and/or Spanish is a political act, I’m not necessarily referring immediately to the content of these literatures. Rather, even before we arrive at topics like ecological and economic exploitation, immigration, and the denouncement of state violence, for many non-Indigenous people throughout the hemisphere being confronted by an Indigenous text, particularly one translated from a marginalized language, shakes the very foundations of what they claim to know about Abya Yala (the Guna term for the Américas) and their place in it. To paraphrase the well-known cliché, “the medium is the message,” and as the medium (language) stakes a claim to Indigenous peoples’ having maintained their ability to sing despite five hundred years of colonial rule (message), many non-Indigenous people tend to be unsettled by the mere notion of “Indigenous Literatures” given that they all too frequently presume these people, cultures, and languages disappeared long ago. For them, the mere translation of these literatures means an ignored colonial history erupts into the present.

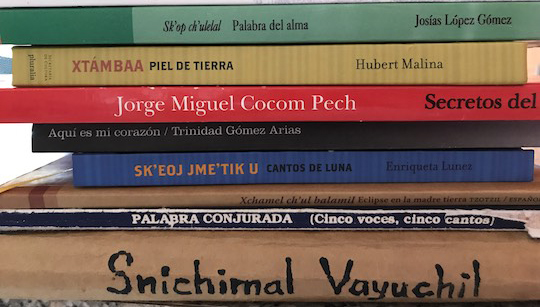

Again, this says nothing of the explicitly political projects of many Indigenous authors and their texts, projects that tend to circulate more on social media like Facebook and Twitter as much as in traditional literary circles. When these works do make it into print they tend to be heavily subsidized by national governments through literary prizes or direct publication, with even independent Indigenous literary publishers like Mexico’s Pluralia frequently collaborating with governmental organizations. In turn, distribution networks tend to further complicate matters as print runs tend to be in the low thousands if not the hundreds, with authors themselves being the primary point people in the distribution of these works. This of course says nothing of authors like K’iche’ artist, poet, and designer Manuel Tzoc Bucup or the Tsotsil poetry collective Snichimal Vayuchi, Indigenous writers whose fierce independence and handmade books reflect a commitment to Indigenous autonomy. Despite the visibility these achieve in Latin América, these factors and the fact that these literatures are articulated in Spanish and/or Indigenous languages means that they remain virtually unknown in a global world dominated at the moment by English.

Notable exceptions such as Cherokee writer Allison Adelle Hedge Coke’s multilingual anthology Sing: Poetry from the Indigenous Americas, Clare Sullivan’s translation of Zapotec poet Natalia Toledo The Black Flower and Other Zapotec Poems (excerpted in our Fall 2013 issue), Zapotec writer Victor Terán and David Shook’s anthology Like a New Sun: New Indigenous Mexican Poetry, Victoria Livingstone’s translation of K’iche’ poet Pablo Garcia’s Song from the Underworld, and Nathan Henne’s translation of Kaqchikel author Luis de Lión’s Time Commences in Xibalbá, are all noteworthy precisely because English translations of Latin American Indigenous texts are so rare. Of course, although these political projects range from the rage of Lión’s Time to the more poetic Mikeas Sánchez’s “Jesus Never Understood My Grandmother’s Prayers,” they tend to be unified in their denouncement of colonialism and its ongoing impact on Indigenous peoples throughout Abya Yala, an orientation these projects share with many Native American and First Nations authors in the US and Canada, and other Indigenous peoples around the globe.

Of course, it should go without saying that Indigenous peoples throughout the Américas possessed a variety of writing systems in a variety of media well before Europeans arrived in this hemisphere. On the one hand, codices such as those of the Mexica and the Maya were recognizable to some extent as “writing” by European invaders, though in infamous cases like that of Diego de Landa this recognition did not prevent the destruction of these works and these writing systems. On the other, forms of recording knowledge such as the Inca quipu have long been denied equal status as “writing,” and have only recently begun to be understood as such. From there, of course, writing with letters has a long and contested history. The Spanish certainly trained indigenous people to use “Latin letters” and to write in their languages for imperial ends, and yet indigenous peoples frequently used that knowledge against the very powers of empire. Beyond visible lettered resistance in arenas such as colonial courts, texts like the Yucatec Maya Books of the Chilam Balam or the K’iche’ Maya Popol Vuh amply demonstrate that indigenous people quickly adopted alphabetic literacy for their own ends and within the context of their own communities. In other words, the use of Latin letters to write indigenous language texts in Latin America is not a new phenomenon, but rather a long-established, complicated cultural adaptation.

Throughout Latin América, the late twentieth Century saw a marked increase in the production of indigenous-language texts and indigenous literatures in general. The specific reasons for this upsurge are complex and vary from country to country, with neighboring countries such as Mexico and Guatemala offering starkly contrasting examples of how these literary movements first took shape. On the one hand, the late-seventies saw a sea change in Mexico’s official politics towards its indigenous populations. While previous “indigenista” policies tended to engage indigenous peoples from without, “participatory indigenismo” sought to empower indigenous peoples and incorporate them into the Mexican state’s bureaucratic apparatus. Not only were many indigenous intellectuals trained as ethnographers, anthropologists, and linguists, but bodies such as the Secretary of Public Education (SEP) supported the publication of bilingual Indigenous-language/Spanish texts. On the other hand, during this same period Guatemala found itself in the midst of a genocidal Civil War in which Maya populations were specifically targeted by military and paramilitary violence. This situation had a galvanizing impact on cultural and political organizing as reflected in the Pan-Maya movement. At the same time, however, the stigmatization of indigenous language and the threat of violence that accompanied speaking these languages in public meant that many Maya authors from the country do not speak a Maya language, much less publish in one. In turn, it goes without saying that a lack of government funding in Guatemala has a pronounced effect on the publication of Maya literature in any language, and as early as the 1980s Maya authors from the country were publishing abroad or independently.

For many of these authors, Spanish-language publication is a precondition of communicating with an audience in their home countries and a necessary first step if their work is ever to be translated into English. As outlined above, in some countries like Mexico, bilingual publications with an Indigenous language and a Spanish “translation” are the norm, whereas in countries like Guatemala, publications tend to be in monolingual Spanish. While these publication trends certainly reflect a pragmatic approach to intercultural dialogue, they also belie the fact that bilingualism (or monolingualism in Spanish) is an expected norm for Indigenous authors just as much as non-Indigenous readers are acceptably monolingual. Translation already haunts these texts, as even those produced in monolingual Spanish are notable for the absence of an Indigenous language. Lión, for example, is said to have been monolingual in Spanish, and many of his works examine painful conflicts of identity that result from one’s culture being under attack. By comparison, bilingual texts that are translated by the authors themselves are not really “bilingual,” but rather composed across an Indigenous language and Spanish. Critic Teresa Dey, for example, quotes the Yucatec poet Briceida Cuevas as saying her poems “have two hearts, one in each language.”

I understand that many scholars and translators don’t work with these literatures because they feel they lack the culture and linguistic knowledge to do so. While I respect this position, I personally feel that the urgency of these texts’ political claims as well as many authors’ desire to be heard on a global scale, take precedence over my own shortcomings. To be clear, I would not advocate grabbing random texts and translating from an unknown culture simply for the sake of translating. Considering the profound stakes of these literatures, the translator bears a particular kind of ethical responsibility towards the text, the poet, and poet’s community. In my particular case, I speak Spanish, have done extensive work collaborating with Indigenous and non-Indigenous colleagues in Mexico, have studied and translated from both Yucatec and Tsotsil Maya languages, and have published my own poetry in English. Certainly, no translator or scholar can work with an intimate knowledge of all Maya languages, much less all Indigenous ones. In particular cases like my translations of Mè’phàà Hubert Matiùwáa’s “Earthen Skin” or Náhuatl Martín Tonalmeyotl’s “The Train,” I relied heavily on the authors themselves to answer any questions I had, as well as upon my own knowledge of different Indigenous philosophies, contemporary Indigenous literatures, forms of speech from ritual incantations to jokes, and Indigenous world views. In other words, as a translator of these bilingual (Indigenous language/Spanish) texts, I am culturally and poetically qualified in cases where my knowledge of a given Indigenous language comes up short.

Instead of trying to hide this lack of expertise in specific languages, I think it’s something to constantly signal, particularly since there are already tensions and fissures between Indigenous languages and Spanish in these “bilingual” texts. It frees the translator from the constraints of only relying on Spanish and allows one to wrestle a bit more with the English rendition as a way to paradoxically highlight the living existence of the indigenous language text. Take the following example from the last line in the poem “Ak’otajel/Danzar/Dance” by Tsotsil poet Cecilia Díaz (found here).

Tsotsil: Vo’one chi ak’otaj ta sokesel areloj.

Spanish: Y yo danzo destruyendo tu reloj.

English: And I dance, unwinding time.

The Tsotsil and Spanish texts align nicely and the last phrase literally translates into English as “I destroy your watch.” The problem with moving this cleanly into English is the reader would miss the profound decolonial operation that occurs between the Tsotsil and the Spanish. “Your watch” in Spanish is “tu reloj,” which in Tsotsil is “areloj,” the prefix “a” denoting second person ownership of the object “reloj,” a term borrowed from the Spanish. By bringing the Spanish word into the Tsotsil text, Díaz enacts a powerful claim to what the watch symbolizes linguistically, culturally, and politically. I feared that leaving this “areloj” or “your reloj” in English would simply confuse the reader, that a Tsotsil neologism for “your watch” would require a footnote, and that a translation of “your watch” would be overly literal to the exclusion of the text’s broader implications. I tried to capture in some sense the metaphor of destruction centered on “your watch” as connoting “time” (as objects watches are wound, not “unwound”), in a way that clearly doesn’t line up with the Spanish at the very least. In not directly translating this phrase, I hope to coax the reader into moving across all three languages and towards a relationship with the Tsotsil text, however tenuous.

As a bilingual Indigenous/Spanish text has at least two audiences (bilingual and monolingual), by translating in this way I similarly hope to construct multiple audiences (trilingual, bilingual, monolingual). In key moments I want the astute reader of English and Spanish to notice the texts don’t always line up, and to wonder what the Indigenous language text actually says. As with the tensions that exist frequently between indigenous language texts and Spanish, the reader who cannot read Spanish likely won’t notice these differences but still derives aesthetic pleasure from the work. In essence, I seek to reproduce the kind of “hidden discourse” that poets such as Yucatec writer Waldemar Noh Tzec actively play with thematically and linguistically in their own works. Is the Spanish version more accurate? Is the English? In the case of my translations of Matiùwáa, I hope the reader moves into a space where they recognize that Mè’phàà is a living language independent of either English or Spanish, with Matiùwáa’s denouncement of the violence of Ayotzinapa now circulating on a global scale in all three.

I would like to thank my friend and collaborator Rita Palacios, as well as Asymptote’s blog editor, for their thoughtful critiques and comments on this piece. Its shortcomings remains entirely my own.

Paul Worley is Associate Professor of Global Literature at Western Carolina University. He published Telling and Being Told: Storytelling and Cultural Control in Contemporary Yucatec Maya, in 2013, and has recently published articles in A contracorriente, Studies in American Indian Literatures, and Latin American Caribbean Ethnic Studies. Stories recorded as part of his research on Maya literatures are available here.

*****

Read more essays from the Asymptote blog: