A new month brings an abundance of fresh translations, and our writers have chosen three of the most engaging, important works: a Japanese novella recounting the monotony of modern working life as the three narrators begin employment in a factory, the memoir of a Russian political prisoner and filmmaker, as well as the first comprehensive English translation of Giorgio de Chirico’s Italian poems. Read on to find out more!

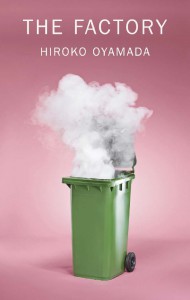

The Factory by Hiroko Oyamada, translated from the Japanese by David Boyd, New Directions, 2019

Review by Andreea Scridon, Assistant Editor

Drawn from the author’s own experience as a temporary worker in Japan, The Factory strikes one as being a laconic metaphor for the psychologically brutalizing nature of the modern workplace. There is more than meets the eye in this seemingly mundane narrative of three characters who find work at a huge factory (reticent Yoshiko as a shredder, dissatisfied Ushiyama as a proofreader, and disoriented Furufue as a researcher), as they become increasingly absorbed and eventually almost consumed by its all-encompassing and panoptic nature. Coincidentally wandering into a job for the city’s biggest industry, or finding themselves driven there—against their instincts—by necessity, the three alternating narrators chronicle the various aspects of their working experience and the deeply bizarre undertones that lie beneath the banal surface. READ MORE…