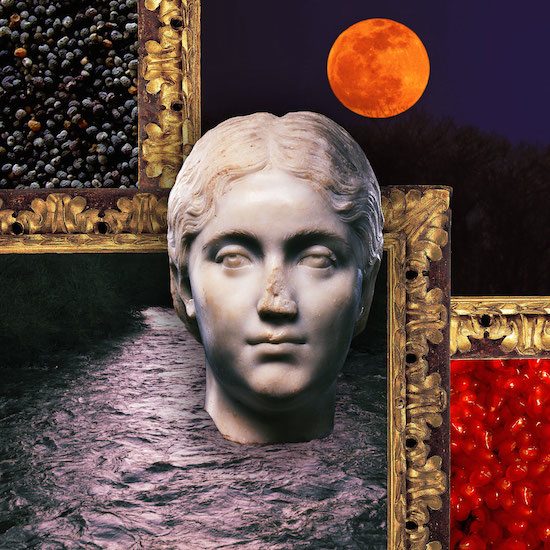

An Acorn Gives Birth to a Tree, the Tree Gives Birth to a Fiddle

An acorn gives birth to tree, the tree gives birth to a fiddle

and you give birth to my star, so the night will be true.

You give birth to it far from here, its light belongs to me and to you,

you give birth to it where no leaf fades, nor anyone’s smile.

We haven’t been of this world for a score of silences now,

a heroic cosmos will not allow our joint death.

The earthly, the real, is real as earth and valid

and death no longer has any power over our breath.

His kingdom does not extend to the green Tree of Life,

what is past has not passed, time is not yet ripe.

Escaped from the clamor, our silence is love,

new images stream from the weeping eye of the soul.

The paired twitch of two silences in one

approaches perfection on a rung of its own.

This wonder-without-a-name tells of its deeds,

the language of atoms has a folksong’s simplicity.

*****