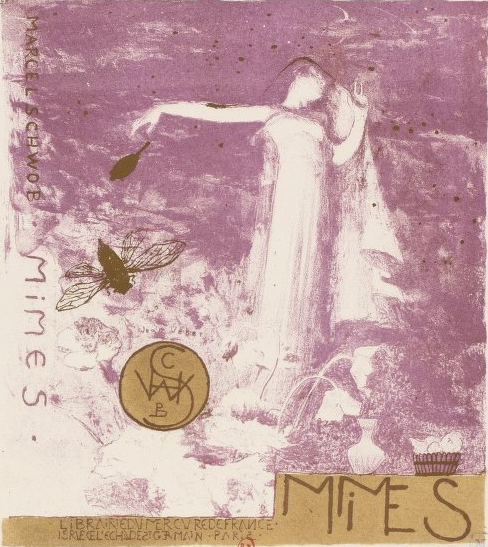

Read all previous posts in Asymptote’s “Mimes” translation project here.

Mime XVIII. Hermes the Psychagôgos

(trans. Sam Gordon)

I conduct the dead, whether they be shut up in sculpted stone sarcophagi or contained in the bellies of metal or clay urns, bedecked or gilded, or painted in blue, or eviscerated and without brains, or wrapped in strips of linen, and with my herald’s staff I guide their step as I usher them on.

We continue along a rapid way men cannot see. Courtesans press against virgins and murderers against philosophers, and mothers against those who refused to give birth, and priests against perjurers. For they are seeking forgiveness for their crimes, whether they imagined them in their heads, or committed them with their hands. And having not been free in life, bound as they were by laws and customs, or by their own memory, they fear isolation and lend one another support. She who slept naked amongst men in flagstoned chambers consoles a young girl who died before her wedding, and who dreams determinedly of love. One who used to kill at the roadside—face sullied with ash and soot—places a hand on the brow of a thinker who wanted to renew the world, who foretold death. The woman who loved her children and suffered by them hides her head in the breast of a Hetaira who was willfully sterile. The man draped in a long robe who had convinced himself to believe in his god, forcing himself down on bended knee, weeps on the shoulder of the cynic who had broken the oaths of the flesh and mind before the eyes of the citizens. In this way, they help each other throughout their journey, walking beneath the yoke of memory.

Then they come to the banks of the Lethe where I line them along the water that flows in silence. And some of them plunge in their heads with all their bad thoughts, and others dampen the hands that have done evil. They lift them out, and the waters of the Lethe have eradicated their memory. And they disperse straightaway, each person smiling for himself, thinking himself free.

*

Sam Gordon: The title of this Mime bemused me somewhat, ignorant as I was of the term “psychagôgos.” Preliminary research revealed that the term, which I believe is interchangeable with Psychopompos, denotes one who conducts the souls of the dead to the underworld, a role I must confess I had—ignorantly—never associated with the messenger god. This informed my decision to retain the conductive idea of “baguette conductrice ” but since the god’s baguette is usually referred to as his “herald’s staff,” I decided to use that, compensating through translating “emmener” (lit. “to take”) as “to conduct.” This I promoted to get around the issue of the syntactically complex, very French structure of the first sentence—it is more typical in French for an object to be promoted before the subject and main verb, but by promoting the verb and modulating the object (i.e. bringing the “dead” out of the “whether” clause) I was seeking to create a new but tolerable sort of strangeness, largely through separating the “I” from the subsequent verbs. In adapting this structure I am presenting Hermes as psychagôgos, while also retaining some of the original’s gleeful mystique.

Reaching again for my dictionary of Classical Mythology, I was amused to read more about Hermes, that mimic par excellence. He was a great trickster: shortly after turning a tortoise into a rudimentary lyre, “Hermes’ next adventure (he was still a baby) was to discover a fine herd of cows, the property of Apollo. He stole the herd, making the cows walk backwards: he also made a pair of shoes out of twigs and wore those back to front, so that the tracks he left baffled Apollo when he tried to discover where his cows had gone… Zeus was amused, and encouraged his son’s impudence.” (Stapleton, M. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Mythology (London: Hamlyn, 1978) p. 104).

The focus in this Mime, however, is on the catholic array of the dead that the god is conveying to the afterlife. Saints and sinners (or the rather more plosive “priests and perjurers”) rub shoulders in death as in life, seeking to wash away their memory (“souvenir”) in the River of Forgetfulness. The cast is described with joyous balance and antithesis, and I have sought to preserve this along with the original’s rhythm and alliteration—the ease of translating the characters deriving not just from the precision of the imagery in Schwob’s text, but also because they are all recognisable types in our times, too. The final line, with its loaded “sourit pour soi” (“smiling for himself”) loses some of the original economy and distaste, but still I think gets across the point that, whatever our memories, our hunger for absolution is as inevitable as our encounter with that rogue Hermes and his herald’s staff.

***

Mime XVIII. The Conductor

(trans. Katie Assef)

Shut them in expensive coffins, stow their ashes in hand-painted urns, embalm and wrap them in spools of linen; people, none of that’s my business. I’m their sorry souls’ chaperone, guiding the troop through the pitch-dark forest.

No bother following us—we take a shortcut for the dead. You wouldn’t know yours from the others anyway, they hold a tight formation: courtesans shoulder to shoulder with virgins, murderers with philosophers, mothers with spurners of motherhood, preachers with perjurers. All whispers of their crimes, their lies and white lies, cling to each other like schoolgirls carrying little pails of dirty water. The one who frequented pay-by-the-hour hotel rooms comforts the one who died before anyone would have her, who masturbated in the tub to bridal magazines. The one who had a thing for dismembering hitchhikers touches the brow of the one who caught a virus from outer space, who cancelled his subscription to linear time. The one who drove a jeep full of babies (precious angels!) embraces the one who guzzled nightshade juice to scour her womb. The one who grew his hair long and rode a wobbly bike around the church weeps on the shoulder of the one who cackled at monks on the street, who told raunchy jokes at the back of the bus. All of them clasping and tugging at each other, dragging their feet—weren’t for me, they’d be wandering for bloody ages.

Arriving at Lethe, that reeking river, I stagger them along its edge where yellow water flows silently by, and it’s the same every time: they run like imbeciles to plunge their hands in the scum, to dunk their heads in it, over and over. Then they rise to their feet and begin to drift apart, the same weird smile engraved on all their faces, poor colossal imbeciles, believing they are free.

*

Katie Assef: I chose to approach Mime XVIII as a jumping-off point to write something new, and to see how far I could stray while invoking the atmosphere of the original. So the challenge in this translation (perhaps “adaptation” is a better-suited term) had less to do with maintaining technical intricacies of Schwob’s prose than with finding a way to seize and heighten certain aspects of the text. I was interested in the subtle—yet arresting—use of persona, particularly in that last line, “Aussitôt ils se séparent et chacun sourit pour soi, se croyant libre.”

These final words twisted my impression of Schwob’s Hermes: suggesting a certain disillusionment and spite, a humanlike frustration with the naiveté of others. I decided to amplify this by having him speak more directly to the reader at the beginning of the piece, and by making him both self-deprecating (“I’m just the chaperone of their sorry souls”) and arrogant (“weren’t for me, they’d be wandering for bloody ages”).

I was also struck by the way in which Schwob’s Hermes catalogues the dead in the middle paragraph, which immediately brought to mind Rodin’s La Porte de l’Enfer. (It’s interesting to note that Schwob translated several of Aleister Crowley’s sonnets on Rodin.) While they march toward Lethe, the dead are in transition; they’re anonymous, yet marked by memories of past lives. I tried to amplify that contrast as well, emphasizing their anonymity by using a common pronoun, and their difference by heightening the specificity of the details that ground each of them in the human world.

(A link to Crowley’s comments on Schwob’s translations, in case it’s of interest)

***

Sam Gordon is a freelance translator working from French and Spanish into his native English. Currently living between London and Aberdeenshire, Scotland, he completed his BA in Modern Languages followed by an MA in Translation at the University of Bristol. His first novel-length translation, of Karim Miské’s Arab Jazz, is out through MacLehose Press.

Katie Assef studied French literature at Sarah Lawrence College and recently completed an M.F.A. in creative writing at Brooklyn College. Her prose and translations have appeared in journals such as EM–Dash, PANK, Weird Fiction Review, Alchemy: a Journal of Translation, and Cerise Press. She lives in Berkeley.