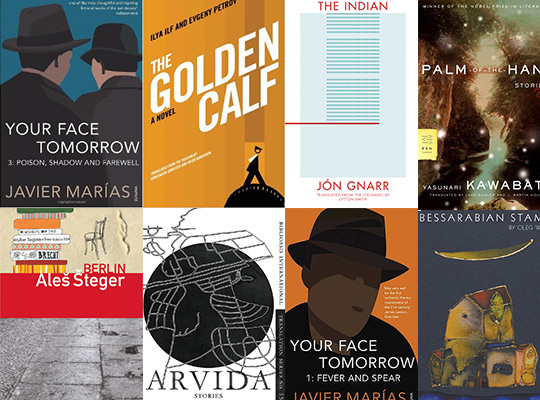

Asked to review my year in reading and from it form reading resolutions, my immediate response is something I need to call an excited sigh. For months now, as a judge for the Best Translated Book Award, all I’ve read are eligible books, books published in the US translated for the first time this year. Yet, there were a few months before that reading took over. For years now, I’ve taken pleasure in not being partway through any books when the new year begins, so as to open each year fresh. This year, Ilya Ilf and Evgeny Petrov’s The Golden Calf (trans. Helen Anderson and Konstantin Gurevich) made for a great New Year’s Day read. (To call it fitting, however, would be a lie.) The novel is hysterical, absurd, and clever, fueled by ambitious and clueless characters, fleeing and bumbling in pursuit of fortune.

Taking advantage of a bitter winter, I read the Your Face Tomorrow trilogy from Javier Marias (trans. Margaret Jull Costa). It is rare for a project so vast to also be unflagging in both its entertainment and ability to find new shades and twists for its ideas: of cultural memories, of what it is to read another human being, of violence and intimacy. But this trilogy accomplishes it. From it alone, I could pluck a number of examples of one of my favorite narrative tricks: to make a scene continue endlessly through digression after digression. Unlike any other art form, the novel is thus able to manipulate the experience of time, both of the readers’ and the characters’.

But yes, this year has been a culmination of reading more and more books the year they’re published. The best way I can think about it is by describing the books that stand out in little, meaningful ways. Starting with where I live, in Vermont, so close to Montreal, Quebec literature has had much of my affection this year. Not just the translations, like the Raymond Bock and Samuel Archibald story collections Atavisms (trans. Pablo Strauss) and Arvida (trans. Donald Winkler)—so similar in their arc as collections and interest in familial depths but with different approaches and destinations—but also classics like the narratively unsettled Kamouraska (trans. Norman Shapiro). Anne Hébert’s novel is as much a story of a women trapped by culture and time, and her murder plot, as it is a stylistic achievement, melding aesthetic with the narrator’s psychology. READ MORE…