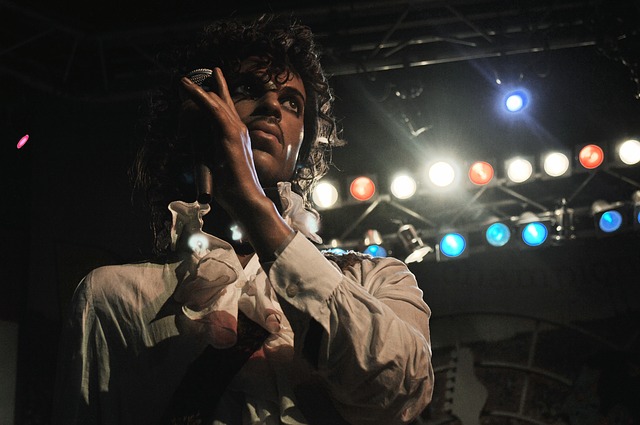

In the same manner that African Americans were forced to create the only original American language, Black English, Prince is a prime example of the creation of a new form, through amalgamation, which evolves from a need to survive. In his article “The Musical Alchemist,” Luis Hidalo states that what sets Prince apart is “his influences, his musical inspirations, the ease with which he assimilates them and then reinvents them with his own personal imprint. Prince has created his own unique style… an incomparable way of making music, a style you can distinguish by the second verse.”

What are Prince’s accomplishments? What did he achieve? First and foremost, his individual freedom. Second, being an encyclopedia of American Music, to paraphrase music critic Nelson George, Prince simultaneously continued the legacy of the African American tradition of Little Richard, Chuck Berry, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, Smokey Robinson, Marvin Gaye, Sly Stone, Maurice White, and Parliament Funkadelic while adding to its narrative the discourse of the post-Civil Rights (which is something completely different than post-racial) African American grappling with place and space in a world of hopes, new opportunities, and continued racial limitations. While Prince was not interested in denying his blackness, per se, he was definitely interested in pondering ways in which he could discuss blackness on his own terms. Next, Prince takes a page from the punk-rock movement of the late seventies and early eighties and fashions what almost becomes a category of alternative music for African Americans. Without this, there would be no Lenny Kravitz, no Terrence Trent D’Arby, no Toni, Tony, Tone, no Me’Shell NdegeOcello, no D’Angelo, no Fishbone, no Living Color, and no Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, at least not in the manner in which we think of them and the manner in which they create and present music. Thirdly, Prince was one of the lone voices of the eighties who wanted ownership, continuing the legacy of Stevie Wonder and passing it on to Jam and Lewis, L.A. Reid and Babyface and Master P. Paisley Park Records attempted to be a real player in the game, signing new acts as well as working with established acts such as George Clinton, Mavis Staples, Miles Davis and Patti LaBelle. Fourth, his work with drum machines and synthesizers expanded on the work of Wonder and revolutionized the technology used in Hip Hop, paving the way for producers such as Dallas Austin, one of the first super-producers of Hip Hop. Austin affirms Prince’s importance and influence on all who follow him by stating, “He’s my total influence in production and songwriting.” READ MORE…