This month in newly released translations, we’re featuring two authors of inimitable voice and style. From the Catalan, a surrealist masterpiece by Ventura Ametller sharply blends history with mysticism in an epic retelling of the Spanish Civil War; and from the French, the latest text by Annie Ernaux returns to some of the author’s most central themes—sex and memory—in a poignant examination of corporeal and psychological navigations.

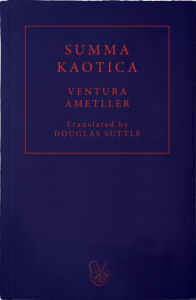

Summa Kaotica by Ventura Ametller (Bonaventura Clavaguera), translated from the Catalan by Douglas Suttle, Fum d’Estampa, 2023

Review by Samantha Siefert, Marketing Manager

A monstrosity of a fish gnashes at a tiger, the tiger leaps towards a gun, the gun is aimed perilously at the prone body of a nude woman. . . It’s all so unexpected and moving, but what do these objects have to do with one another—or with anything at all?

Such is surrealism: the challenge of reconciling the disparity of absurdity. “Everything leads us to believe that there exists a spot in the mind from which life and death, the real and the imaginary, the past and the future, the high and the low, the communicable and the incommunicable will cease to appear contradictory,” declared André Breton in his manifesto. Riding on the coattails of Dadaism, surrealism emerged as an impulsive reaction to the tragedy of the First World War: If reason had resulted in such great suffering, then what good was a movement rooted in realism?

The antithesis of reason, then, was the way forward, and the efforts of the avant-garde were so resonant that they continue to exist today as comfortable figures of popular culture, where the discordance of fish, tiger, and gun feel almost familiar in Salvador Dalí’s famous painting, “The Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening.” The surrealist world of letters, however, leave room for discovery.

In Catalonia with Dalí at the beginning of the twentieth century, the writer Ventura Ametller—the pen name of Bonaventura Clavaguera—was hard at work, producing a prolific collection of poetry, essays, and novels that turn the world upside down in raucous prose, described by essayist Lluís Racionero as “Dalí in words.” His work has remained only quietly appreciated, but perhaps the time has come for that to change with the new publication of Ametller’s groundbreaking magnum opus, Summa Kaotica, in a masterful translation from the Catalan by Douglas Suttle. READ MORE…