Happiest of Fridays, Asymptote pals! This is the first week Katrine, new blog co-editor, is on board—so let’s give her a big web-round-of-applause (tapping on the keyboard in the comments section helps). Hi Katrine! You might recognize Katrine because she was a judge for the Best Translated Book Award so, yeah—she’s a celeb.

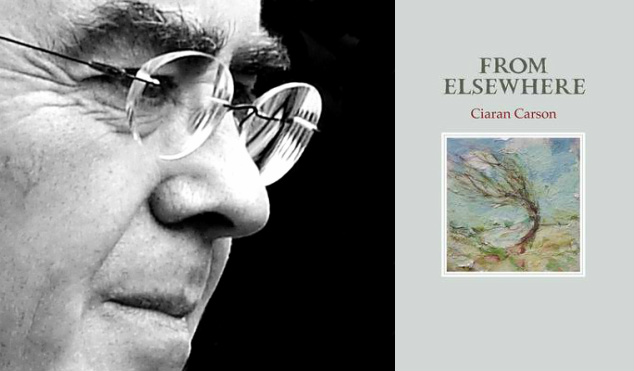

Speaking of celebs, our former Central Asia Editor-at-Large, Alex Cigale, recently guest-edited a section on Russian poetry over at the Atlanta Review—it’s definitely worth checking out (and look for a blog interview on the guest-editing process soon). If you are a fan of the Norwegian Nobel Prizewinning bard, Tomas Transtömer, here’s a treat—his final interview given before his death, in translation. And, speaking of poetry—the New Yorker has an interesting piece on Jihadi poetry and what it means to share some words.

Multitasking artists: American playwright Tennessee Williams took up painting, once (just like American ex-President Dubya, whose outsider-art paintings I frankly prefer). And Dany Lafferière, a Haitian novelist who came of age in Canada, is the first non-French citizen to be admitted in the prestigious Académie Française.

What are your favorite authors’ favorite words? Here’s a little list. And what’s your favorite curse word—it might not have existed too long ago (except, of course, for “fart,” which has stood the test of time).

How does it feel to write and never be read? Most of us know, all too bitterly. But perennial Nobel-speculation and speculative-fiction writer, Canadian novelist/poet Margaret Atwood, has written for a library that won’t be available for another one hundred years. Will we all be screened-up e-readers by then? The Chicago Tribune thinks not. Nine hundred years later, we’re still collectively obsessed with the old Icelandic god, Loki, though. What gives?

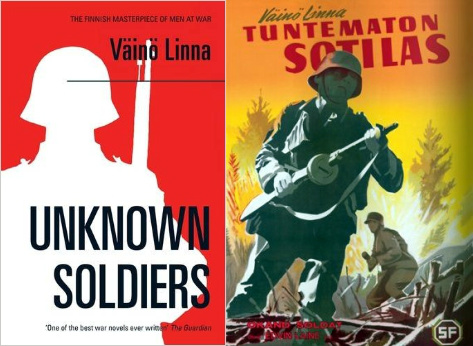

Finally, please, and for the love of God—unless you are Karl Ove (in which case it is already too late): delete your memoir. If it’s written from a female perspective, it’s less likely to win any big prizes, anyway (ugh), unless, of course, it is the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction (congrats Ali Smith for How to Be Both, this year’s prizewinner). Prizes aren’t always great, though: even judge Marina Warner (from the Man Booker!) is bemoaning the dearth of world literature available in English—good thing journals like Asymptote are working to buck that trend.