Select translation:

Bedstefar

Ma petite fille,

Salome, mit barnebarn,

mi nieta

para ti soy “Bedstefar”,

tu única palabra en danés.

Le meilleur père, père

de ta mere,

ton grand-père danois

en danois.

Cubana de padre, francesa

de madre

y yo, tu raiz nórdica.

doce por cien

y medio, lo que hay de danés

en mi poesía

ou d’alcool

dans une cépage de bonne qualité.

De moi t’as déjà herité

Plus que ta mere:

un mot, an

heirloom du nord:

“Bedstefar”

avec tout ce que celà

veut dire

y con todo lo que tu dirás

cuando me llames,

quand tu m’appelles.

When you call my name.

Blodets bånd, siger vi.

Barnebarn, grandchild, petit en–

fant,

blood of my blood

a bond which cannot be severed.

Más que un vincula, plus que un lien,

yet nada

nothing

rien

unless we invest it with meaning.

So, what sense

qué sentido tuvo para mí

tu nacimiento?

Hvad betød din fødsel for mig,

en far

der aldrig er blevet kaldt, har

hørt sig kalde

far

og kun sjældent

rarement

a pu agir, actuar,

como père?

¿Qué tal te sientes como abuelo?,

me preguntaban,

and I was at a loss, no supe contestar

comment je me sentais.

I didn’t feel any different, no notaba

ninguna diferencia

and could not see why I should have changed.

Pasaron cinco años, cinq ans

sans practiquement se voir

y solo ahora me doy cuenta,

only now,

gazing back at a gap of five years,

do I realise how you, ou plutôt

ta presence,

changed the perspective of my life,

gav mit liv

et dybere perspektiv

making both past and future unfold.

Probablement, je n’ai jamais occupé

la place du père,

dans la vie de tu mama.

Like a fool I offered her up

as a sacrifice for my love to her mother

y su abuelo, mi suegro, me la arrancó.

That man, tu bisabuelo, now dead,

rife with heirs and hardly mourned

stole my daughter and supplanted me

leaving me,

dejándome,

a childless, self-deceitful

papa chatré.

Salomé, nieta mía,

para ti soy todavía poco más

que una palabra, but a word which,

ahí dedans,

contains,

esconde,

gemmer et løfte, a

meaning and promise

that we both must explore:

din “Bedstefar”,

la meilleur père

de ta mere.

***

Offering

The pain,

el dolor de esas dulces disonancias.

Le ton aigu, den skærende

intonation

pa nippet til… a breath

from keeling over.

Et smertefuldt, jublende skrig.

Like Coltrane

we must squeeze the reed, estrujar

nuestra alma

hasta que la nota se quiebre, indtil

kernen spaltes, permitiéndonos

seguir fluyendo

indtil

sjælen kælver

og døden os skiller

until we cave in

and death do us part.

***

Django’s Lullaby

Toutes les chansons d’amour,

todas las flores de primavera y los

colores de otoño

que je t’aurais cueilli

se me han marchitado.

The songs that my thoughts of you

stirred in the wind

are now a dry rustle, an autumn lullaby

perhaps.

Fugle som trækker mod syd,

pájaros,

birds of passage.

Que venga la nieve, la

neige, la manta suave y blanda,

the sweet, forgetful snow

that will cover all the wounds

calmará el ardour de las heridas

and the broken stems

with its cool whiteness,

su fría blancura.

La neige de noviembre,

november

sur les petals bleus de mes pensées

de nous.

Bedstefar

My granddaughter,

Salomé – ma petite fille,

mit barnebarn,

mi nieta –

for you I am “Bedstefar”,

the only word you know in Danish.

“The best father”, your mother’s

father,

the Danish for

your Danish grandfather.

Cuban on your father’s side, French

on your mother’s –

and me, your one Nordic root.

12.5%:

like the Danish in my poetry;

or the alcohol content

of a fine wine.

You’ve already inherited

from me

more than your mother ever did:

a word, a Northern heirloom:

“Bedstefar”

and all that word means

and all that you mean

when you call me,

when you call me it.

When you call my name.

Blood ties, we call them.

Barnebarn, grandchild, petit en-

fant,

blood of my blood

a bond which cannot be severed.

More than a bond, more,

yet nothing,

nada,

rien

unless we invest it with meaning.

So,

what did it mean for me,

your birth?

What did your birth mean for me,

a father

who has never been called,

never heard himself called

father,

and has only

rarely

been able to act

as a father?

How do you feel about being a grandfather?

people would ask me,

and I was at a loss, I didn’t know how to answer,

how I felt.

I didn’t feel any different, nothing

tangible,

and could not see why I should have changed.

Five years passed

and we scarcely saw one another,

and only now do I realise,

only now,

gazing back at a gap of five years,

do I realise how you, or rather

your presence,

changed the perspective of my life,

made that perspective deeper,

making both past and future unfold.

I suspect I never really fulfilled

the role of father

in your mother’s life.

Like a fool I offered her up

as a sacrifice for my love to her mother,

and her grandfather, my father-in-law, tore her from me.

That man, your great-grandad, now dead,

rife with heirs and hardly mourned

stole my daughter and supplanted me

leaving me,

dejándome,

a childless, self-deceitful

papa chatré – a castrated father.

Salomé, little one,

for you I am still scarcely more

than a word, but a word which,

deep inside,

contains,

conceals,

holds a

promise and a meaning

that we both must explore:

your “Bedstefar”,

“the best father”

of your mother.

***

Offering

The pain,

the pain of this delicate discord.

The pitch set high, the intonation

cutting,

on the verge of… a breath

from keeling over.

A painful, joyful cry.

Like Coltrane,

we must squeeze the reed, wring out

our souls

until the note cracks, until

its core is cloven, so we can

keep on flowing

until

our souls cave in

and death do us part.

***

Django’s Lullaby

All the love songs,

All the spring flowers and

autumn colours

I gathered for you

have withered in my heart.

The songs that my thoughts of you

stirred in the wind

are now a dry rustle, an autumn lullaby

perhaps.

Birds that fly south for winter;

birds of passage.

Let the snow come,

its soft and tender blanket;

the sweet, forgetful snow

that will cover all the wounds,

soothe the stinging cuts

and broken stems

with its cool whiteness.

November snow,

on the blue petals of my thoughts

of us.

***

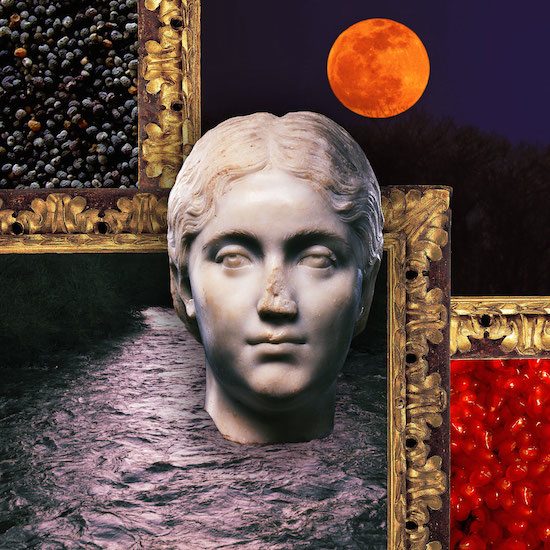

Illustration by Dinah Salama.

******

Peter Wessel is a Danish-born poet who has divided his life between his homes in Madrid and the Medieval French pilgrim’s village of Conques-en-Rouergue (which he considers his second birthplace) since 1981. He teaches a university course titled “Rooted in Song—the Role of African Americans and Immigrant Russian Jews in the Creation of the American Dream” and defines himself as a musician who expresses himself through poetry. Peter’s last two books Polyfonías (2008) and Delta (2014) are multilingual poetry collections both of which include recordings of his readings in dialogue with the musicians from Polyfonías Poetry Project. He blogs at www.pewesselblog.com.