As 2025 draws towards its close and we begin to reflect on the year, one unescapable fact is that it was another year of the world at war, when the terrors wrought by modern weaponry and those who deploy it has become only too clear. In this context, we would like to revisit our feature on the work of Mahwish Chishty from our Summer 2014 issue. In War Machines, Chishty painted traditional Pakistani ‘truck art’ over photos of military drones, calling attention to the terror of the modern war machine by contrasting it with a representation of beauty. Chishty’s work feels as resonant and relevant today as it did then, both as a way of giving voice to horror and of resisting it.

Q&A with Mahwish Chishty

For those of our readers unfamiliar with Pakistani ‘truck art,’ can you explain what it is?

‘Truck art,’ sometimes referred to as ‘jingle art,’ has recently become a cultural phenomenon in Pakistan. In ‘truck art,’ trucks (but also rickshaws and buses) are painted inside out, in elaborate colors. The decoration of vehicles is, of course, common practice in many countries but Pakistani (and Afghani) truck art is unique because of the pervasiveness of its decoration. Virtually all privately owned trucks in Pakistan (and Afghanistan) are decorated in a way that varies from region to region. I was introduced to this cultural practice back in 1999 while I was attending the National College of Arts in Lahore and this phenomenon of myriad colors and styles superimposed over dull grey metal has always intrigued me.

Elsewhere you have mentioned that culturally loaded text sometimes accompanies the colorful ‘truck art’ and you appropriate both text and ‘truck art’ in your miniature paintings of military drones. Firstly, can you tell us more about this text, and secondly, what do you hope to achieve by appropriating ‘truck art’ in your depiction of war machines?

In the ‘truck art’ genre, certain texts are repeatedly written and, because of the beautiful way in which they are repeatedly written, aestheticized for the viewer. Content-wise, these texts may express the truck owner’s political or religious leanings; they may also be poetry, or movie trivia. In my paintings, I either borrow the imagery and texts wholesale, or improvise.

By presenting the colorful iconography and texts within the silhouette of a drone, I hope to open up a conversation about omnipresent ‘truck art’ and the not-so-visible presence of drones in that region. ‘Truck art’ originated in Afghanistan and spread across the border into Pakistan—the same Pakistan/Afghanistan border that is now a war zone. Truck drivers use their mode of transportation as a colorful form of self-expression; drone operators, however, are invested in remaining anonymous. In nature, bright colors attract attention; in art, they also serve the practical purpose of drawing viewers into the work. And just as in nature, where certain combinations of bright colors index an animal’s deadliness, here the coded visual language, upon closer examination, reveals sinister elements such as snakes, guns, swords, spears, grenades, and dead fish, among others.

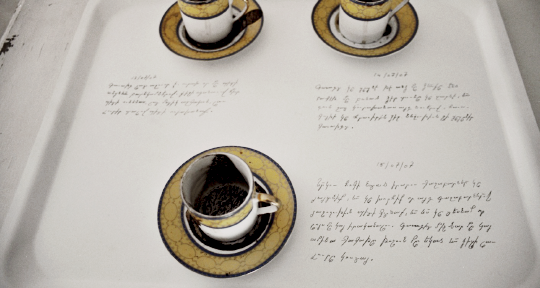

What is the significance, if any, of tea stains on many of these works?

Tea staining has been used in traditional miniature painting for thousands of years as a way to start a painting with a neutral background instead of stark white. For these pieces, it works insofar as the texture and color of the tea stains depict well the aerial landscape of the Pakistan/Afghanistan border, i.e. the view that drone operators would see on their computer monitors 10,000 kilometers away from the war zone.

As recently as a month ago, Pakistani fighter jets carried out raids on suspected militant hideouts in the tribal North Waziristan region, killing 80 militants. What do you think art can hope to achieve, against reality?

Art is not detached from reality; it is reality, often dark and violent, that impels artists to create work that may address that reality. In fact, many artists from this region have altered their artistic practice to express their concern and dissatisfaction about the bloodshed in that region. As a Pakistani living in the US, I’ve found it even more necessary to create work about issues that concern my people and me.

Revisit the feature on Chishty and the portfolio of her work here.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: