The narrator, distracted not only by refugees circling in cars but also by an appetite that drives her into the kitchen to snack, ruminates on the recording of deaths on the Internet, on the smuggling of a slaughtered lamb from Damascus to Beirut for a family celebration, and on the difficulties of speaking in the midst of traumatic events. The narration is unvoiced so, to follow the text, one must watch as the camera lingers over possessions packed into cars, and then slowly, clinically, scans over cuts of lamb as one might find arranged in a butcher’s shop.

Of course, the story of being unable to write a script because of being distracted by refugees and her own pregnant body’s cravings is the script. The third-person narration occasionally slips into first person, blurring the distinction between fiction and autobiography, and between historical record and the mundane. At one point, the narrator asks, “Hold on. Was this someone else’s story?”

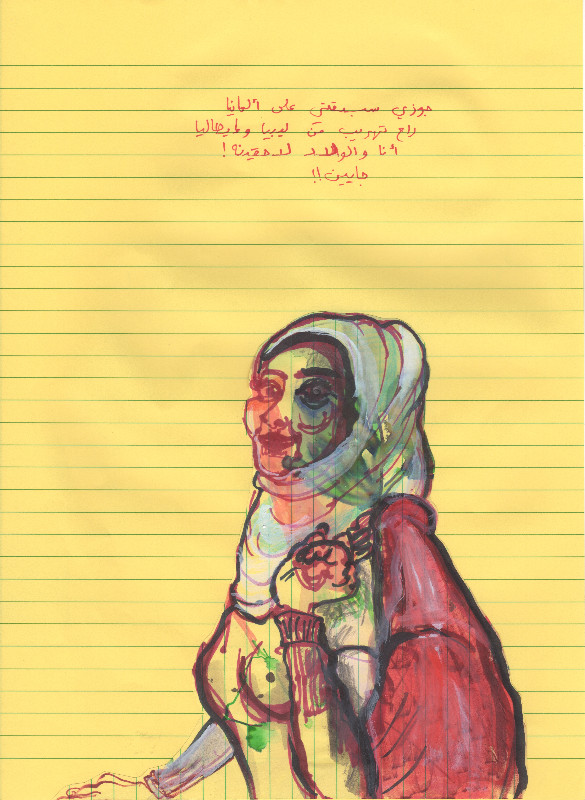

Mounira Al Solh, born and raised in Beirut, is now based in the Netherlands. Her work ranges from video and performance-based projects to paintings and installations. Many of her works address experiences of displacement, war, linguistic identity, language acquisition, and difficult but fruitful exchange among multiple mother tongues. The ongoing series I strongly believe in our right to be frivolous—recently showcased at the Art Institute of Chicago—consists of informal portraits of displaced Syrians along with notes taken during conversations with them. Having begun when the artist was living in Beirut, the series developed as she began inviting refugees to her studio, and the studio became a lively meeting place for sharing experiences as she drew likenesses and jotted down conversation. In its recent incarnation at the Art Institute of Chicago, the artist, through the Syrian Community Network, met with Syrian immigrants to the United States.

How did the project I strongly believe in our right to be frivolous originate, and how has it evolved since its inception in 2012? What is the significance of being “frivolous” (as suggested by your title)?

In 2011, as I was pregnant with my daughter, the Syrian revolution started, and I was in Beirut. Having a child while other children are being detained, arrested, tortured, and killed, was very intense. The first kids who sprayed “freedom” on the wall of their school in Daraa were arrested and harshly punished, one of them killed. I thought that my daughter would come to a better place, since I was born amidst the Lebanese civil war, but, in fact, she was being born at a time when the situation had escalated, and all kinds of weapons were being used against the people in Syria. In fact, my mother comes from Damascus, and when we used to live there, while escaping the Lebanese civil war, we also lived and worked on family farms in Ghouta. So I have spent chunks of my childhood in Damascus and in Ghouta with my grandmother’s family.

In any case, in the year 2006, as I was finishing my studies at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, I made a video piece, Rawane’s Song, in which I stated that “I have nothing to say about the war,” meaning the Lebanese civil war. At that time, everyone expected Lebanese artists to speak about that war. It was also generational, as people who grew up during the Lebanese civil war found the only way to survive was by not speaking about the war, but about survival instead. When I was a young teen, I had the privilege to live the changes that occurred on the ground in Lebanon, the abrupt and absurd end of fifteen years of civil war, and the shift to a postwar time (or perhaps to a suspended civil cold war, as some people called it).

Ironically, when I had finished making Rawane’s Song there was a war again in the summer, when Israel invaded Lebanon and bombed its bridges in a fight against Hezbollah, who had kidnapped a couple of soldiers to tease and provoke Israel. After this war, fighting factions would strengthen and become more popular. Anyway, at that time, I did not refrain from showing Rawane’s Song, and I did not refrain from taking a highly ironical position towards “speaking about the war,” even though we were being bombed and the country was devastated.

But in 2011, and in 2012, things changed. I wasn’t a kid anymore, and the scale of the war in Syria is not comparable to any war anyone has recently lived through! It is also a war of the “live death image.” For the first time in history, as people die, they are recording their images and sending them virally for others to see. I heard about a family who saw their child being shot in his car on YouTube. That’s how they learned about and “saw” his death.

On a personal level, I saw the reversal of the movement I had experienced in childhood: we used to escape to my mother’s country of origin, Syria, when Lebanon was too dangerous. And now it is the Syrian people who need refuge; they are coming to little Lebanon.

As I was saying, in Lebanon in 2012, in my neighborhood, many young people, activists, musicians, and filmmakers, started coming to settle, escaping the ferocious iron grip of the Syrian regime. Being in Beirut at that time, you feel you are looking at the war in Syria through a mirror: you are witnessing by the hour escaping families, whole neighborhoods, and villages. These are individuals who just a few hours earlier were exposed to war from all sides—whether the Syrian regime, or any of the other fighting factions, whether bombs, aerial attacks, snipers, kidnappings, checkpoints, shootings at civilians during demonstrations, after demonstrations, before demonstrations, shooting at those burying their dead, arrests of the wounded, or killing of the arrested wounded.

On top of that, when Syrians started to come en masse to Lebanon, the Lebanese people were still traumatized from the civil war. For many, it was difficult to distinguish between the Lebanese war days, the Syrian army, and the Syrians escaping the war in Syria—mostly those against the Syrian army, and those being killed and persecuted by the Syrian regime, but of course also at times by ISIS and other fighting factions.

So this is where my project started: but I had huge doubts about how to be involved and if I should be involved at all because of my position as someone who was born and grew up during the Lebanese civil war.

It was by re-reading Mahmoud Darwish, the amazing Palestinian poet, that I was liberated. I read a touching interview in BOMB magazine in which he speaks about the impossibility of writing about existential matters while under siege. I understood, then, that my position of “not to talk about the war” is irrelevant: there is no position to take, we are in the middle of things, we have to act. I had to act. And if I didn’t act, I would not be able to live. The scale of the disaster is only roaring bigger, even if Lebanon is now a safer place, but we can’t sleep at night, constantly watching the disaster nearby on our phones and laptops, witnessing the disaster each second by watching the faces of the people who escaped, and by carving a growing visible wall between Syrian newcomers and the Lebanese. I wanted to break through that wall.

I started inviting people to my studio, Palestinians who lived in Syria and were born there, and who considered themselves Syrians except (as usual) they were forbidden from having a Syrian passport (with some exceptions of course), and who were escaping from the Yermouk camp in Damascus. At that time, it was being bombed by the Syrian regime under the excuse that Islamists were found there, and thousands escaped to Lebanon.

I invited Syrians who were escaping from Homs, from Deraa, from Damascus, from Reqqa, Idlib, Salamiyeh, from Latakia, Jableh, you name it . . . but there was hardly anyone at that time from Aleppo. The Aleppo “chapters” happened at a later stage.

I also met with many people who were not with the Revolution nor against it either, who didn’t really participate in politics, yet their houses were bombed, their children were arrested.

My studio became a meeting place where I’d invite people over, and I’d pull out my notepad, make drawings, and write down our conversations. The drawing and the writing would happen at the same time. Sometimes I was more focused on the drawing, and sometimes more focused on the writing.

I personally wanted to recollect my Syria through the stories of the people, but also to live its diversity, its love stories, and its little unwritten matters that happen on the side of the war. When people came over, we spoke about everything! Also, we spoke about frivolous matters. I once met a man who told me that his residency permit wasn’t issued in Lebanon, and that anyway it’s too expensive for him to get one, so in the meantime he watched Friends, the infamous American television series, and he didn’t go out at all; he might have stayed a couple of years just doing this, in order to remain invisible to the Lebanese authorities.

When I was young, also after the first years of the end of the Lebanese civil war, maybe around 1996, Darwish was invited to speak and read his poetry at the UNESCO Palace in Beirut, which is near the Mar Elias Palestinian camp and not too far from the Sabra and Chetila camps. I won’t forget how the streets were closed, and thousands of people walked to the stadium, at sundown, to listen to Darwish speak in the dark. The streets of Beirut were still dark during those days, still affected by the war. When Darwish utters his poetry, it’s about breaking the Arabic traditional measures; it’s about using a modern language affected by how the Palestinians have been scattered globally after being kicked out of their country. It is about the scattered homeland, but it is also about love, the beloved one, passion, birds, sounds, music, rhythm.

My work is a collection of hundreds of encounters, captured by writing and by drawing the moments with each individual and family I met; they capture the mood and the content of our conversations. The work indirectly reflects the war, displacement, detention. In the conversations, we spoke about Syria before, during, and after the Revolution, about love, divorce, big ideas as well as the tiniest details of daily life, about nothing as well.

In your video The Mute Tongue (2010), you stage nineteen Arabic proverbs that have been interpreted by a non-Arabic speaker, the Croatian artist Siniša Labrović. Can you say more about this work?

In this work, I tried to reenact Arabic proverbs, to visualize them. The reenactment is silent, except with ambient sound. It is very hard to trace the provenance of these proverbs. Some are also found in other languages. Proverbs are like embroideries; you can never tell where they really originated from, and each place has the skill to relate them to its own context, but, in fact, they are quite universal. This is why it was a nice escape plan not to work with a protagonist who had a typical Arabic face, I thought. And then I was introduced to Siniša Labrović, who had also performed Croatian proverbs.

I am fascinated by My Dick in My Dick, Kiss Me Again, After Eight, All Mother Tongues Are Difficult and their sisters, a web-based project for Ibraaz. The project, including embroideries, collages, and found items, along with texts, reads like a meditation on language and translation, especially the transference of Arabic letters and terms into a Western context. Can you talk about how this project developed?

That project was commissioned by Ibraaz, and it ended up being a reflection on my works. It included excerpts from the series After Eight (2014) and another one titled All Mother Tongues are Difficult (2014).

All the works I make are forms of research. Many are the result of reading, reading groups I took part in or initiated, and embroideries I did as I was reading.

My language research came when I was applying for Dutch citizenship and needed to pass an exam. That exam is supposedly about the language but, in fact, it confronts the “immigrant” or the “refugee” or the “exiled” with Dutch habits, in a way that even Dutch friends who tried to take that exam failed. The questions are sometimes absurd. Anyway, having to learn that language, not out of love or “culture” but rather out of necessity for the passport, I saw how sometimes a language can be a threat, a weapon, an entrance ticket, a tool of torture, of prejudice.

To learn Dutch, I went to Antwerp, since the Dutch in Amsterdam’s art circles want to speak English. I was invited for a residency at Air in Antwerp, and I incorporated learning Flemish (like Dutch but with a different accent), into my residency schedule. I set about learning Flemish in a home for people who had schizophrenia. I conducted a workshop with them, and I asked them to write letters about love. We did that together. I stayed about ten days. Those letters are now “hiding” in my magazine NOA (Not Only Arabic), the third issue, which is about prejudice. It’s possible to view the magazine by appointment only.

After this, I also tried enrolling in the Belgian government’s cheap language courses, trying to learn Flemish while in Antwerp. There, yearly, about twenty thousand people come to Antwerp to take language courses to “integrate” into Belgium. When I tried to enroll, though, the staff noticed I had a Dutch residency permit, and they apologetically refused to let me enroll, since I wasn’t going to become a citizen in Belgium, but in the Netherlands. I convinced them that I would like to film what was happening during the week everyone was coming to enroll, and they allowed this. I made a short video documentary about the language center as part of my research into language and immigration.

I met an Iraqi woman who volunteered at the language center. She had lived in Syria for five years after having escaped Iraq, and when the Syrian war started she made it to Belgium. Her colleague was a woman from Bangladesh, and they spoke English together. As I was filming the two women trying to communicate, the Bengali said, “All mother tongues are difficult.” Some of the embroideries included on the Ibraaz website are inspired by these encounters in the language center, where twenty thousand people go to learn Flemish, and many volunteers of various backgrounds come to help. It was a friendly, vibrant place.

At the language center, there was an exhibition on the history of Belgium, a timeline along with a few images. There was a book left for visitors to inscribe their remarks. I photographed that book page by page. I saw remarks by people from Syria, Iraq, India, Bangladesh, and a few from Belgium, each one reflecting on Belgium’s history, or on their personal experience as people who now live in Belgium. It was amazing to note the different impressions and opinions written in different languages, with mistakes in Arabic or Flemish or French, the mixing up of languages. It is just a brilliant document. It reflects anger, but also forgiveness, and recognition of a relationship to Belgium.

In My Dick in My Dick, Kiss Me Again, After Eight, All Mother Tongues Are Difficult and their sisters, you take up the Arabic translation of “mother tongue” as “mother language.” You ask, in the context of Kamal Youssef El Hage’s translation, “What is the difference between a language and a tongue?” How would you yourself answer this question, in terms of your own practice as an artist and researcher?

In Arabic, we say the “mother language,” not the “mother tongue.” According to Jacques Aswad, a philosopher, poet, art critic, and translator, “mother tongue” is a relatively new concept, which was first “brought” to the Arabic language in the twentieth century by Kamal Youssef el Hage. Because Arabs did not consider “other tongues,” maybe, so there was no concept of “mother tongue” . . .

Jacques Aswad accepted my invitation to give a talk during a solo show I had in Beirut at Sfeir-Semler gallery. The title of the show was All Mother Tongues are Difficult. Jacques spoke about Kamal Youssef el Hage. (He had been killed, but his family members attended that talk, which was very special.) Another talk was by Ahmad Beydoun, who had written in the eighties an article titled “Kalamon,” in which he studies the origins of the Arabic letters. I also made works based on “Kalamon” and his research into the origins of the Arabic letters.

Going back to “tongue” as opposed to “language,” I think that the tongue is the immediate tool of oral language. My video The Mute Tongue reflects on the concept of “mother tongue” and the impact of mother tongues on people’s visual “luggage.” One of the Arabic proverbs I reenacted was “Hair grew on my tongue.” This phrase refers to the experience of repeating things over and over again but no one understands or listens to you. The image of the tongue is an embodiment of language; in this case, there is hair that grew on that tongue, as if to obstruct its glittery, slippery texture, to make the words unclear or inaudible.

Language is broader as a concept than “tongue.” A tongue is a tactile thing, an entity of its own, a tool for spoken language, and it is also more physical. In that sense, Lisan al Arab (Tongue of the Arabs) is one of the dictionaries that reflects this embodiment of language.

When you look up words in Arabic dictionaries, it’s not like in English or French. You have to get back to the origin of each word. For instance, to look up a name like “Mounira,” you have to go back to “Nour” (a root of the word), and then under “Nour,” you’d find hundreds of derivates. When a person looks up a word in Arabic, she or he has to think a bit mathematically, to clean up the word, to clear away the glitter and the extras, to reach its origin. My work Samaa/Maas plays with those roots.