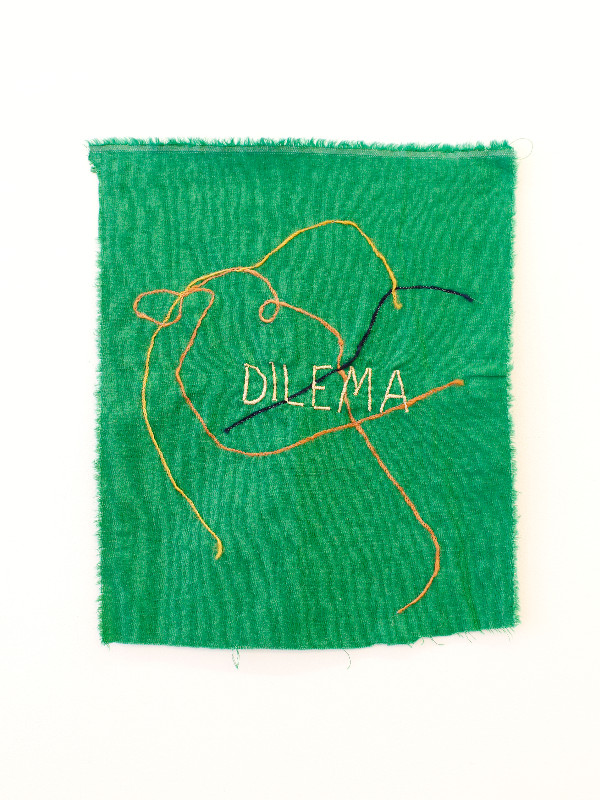

The power embodied in the act of naming and describing the nature of experience is in a constant state of friction in her work. Take the words embroidered in notebook pages made out of felt in the “Costuras em feltro” (“Stitches on Felt”) series. Words such as impossible, indelible, and inexhaustible are scattered throughout the lines of the pages, acting as the confessions of a story that could be beginning or ending, depending on the reader’s interpretation.

In “Costuras em tecido” (“Stitches on Textile”), short phrases that suggest oneiric scenes and intimate confessions addressed to an absent receiver anchor that observer’s presence on the fabric in order to demand an answer that might never come. Phrases such as “I brushed my teeth to speak with you on the phone” and “There was a lion in your bedroom door on top of a mat and you didn’t care. I was scared,” reveal, as much as they conceal, traces of a wider story.

The handmade embroidered calligraphy summons all the emotional intrigues embedded in the act of recreating the stories. Words sewn on colorful fabrics or erased from maps taken out of old atlases signal a reconstruction of key moments in her life. These are moments that she knows she cannot change but that she can write about to make them her own, disassemble them, and reimagine what could have been.

What’s left is an overarching question: is language precise enough to overcome the gap between desire and its discourse? Recently, she participated in Far from words, a performance work created by Thomas Dupal for the 33rd São Paulo Art Biennal Affective Affinities, as part of Sofia Borges’s curated segment. During the performance, Guga danced all over the main hall of the Biennale Pavilion made by Oscar Niemeyer, asserting her presence, though this time without the aid of words or images.

The performance points to one of the key elements that stand out in her work: the transparency through which she reveals herself and invites the viewer to be a witness to her story. It is in the dialogue created by the words and the fluidity of her body, along with graphic elements that populate her work—river-like lines and corporeal silhouettes—that she introduces new clues for the observer to consider, producing multiple resolutions to the stories she is willing to tell.

What are the stages of your creative process, from the initial idea to the moment of executing the piece?

Everything begins in my notebooks. The notebook, for me, is a space of immense freedom. A space with easy access and no filter. A space that allows for errors, dreams, words, at each moment. It is a space I can always re-access. I return there when I’m drained. It grounds me and makes me remember the places I have been, the books I have read, the dreams I would otherwise forget.

I always go back to my notebooks when I begin a new project. It preserves my sanity. It’s where I store my past, present, and future. Flipping a page is like turning a corner; there is always something waiting for me. What unfolds from this is what catches my eye and is transformed into an image.

In the series Lugar Nenhum (Nowhere), you utilize a variety of maps and modify them. The names of countries, oceans, and other spatial formations are erased by means of different techniques. How do you understand the relationship between image and word? How do you change the meaning of maps through the erasure of names?

Maps have been present in my projects for some time. When I was in college, my grandfather was getting rid of many of his books, and I took a huge stack of old atlases that had no other use; they had become obsolete because of the simple fact that everything in the world is always changing. Borders disappear, rivers spring up, cities grow, and the atlases are there, trying every year to account for everything, an ever-frustrating endeavor to organize, categorize, and explain the world in a book. For me, atlases were an attempt to represent the truth, a book that people could access to understand the true distances between one person in South America and another in Europe. In this book, people could learn about the depths of the oceans, about the ocean currents, the winds, the climate of each country. What the forests are like, about all the animals that live within them. We could talk about how many inhabitants there are in each city (imagine how crazy that would be, we would have to publish thousands of books every second). Atlases served, then, as a means for us to be sure that we ourselves were on this earth, everyone at some reference point. With this in mind, my first project was, using those maps, to remove all the names that appeared with a utility knife. Thus, they were no longer places, they were no longer possible to find. There was no further explanation.

After this, the map project unfolded in different directions, placing labels as a way of piling names on top of names, joining different territories in one solitary space, merging boundaries, creating new countries, new destinations, and other experiences.

I completed this project in 2009 and it is still the guiding principle of my research.

With it, I understood the power of words, as much in their absence as in their repetition, or in their displacement. A word creates new meaning depending on where it is. The same word placed over blue is a different word when it’s over yellow.

In the series Costuras em tecido (Stitches on Textile), a series of phrases and words are stitched onto fabrics of different shapes and colors. Some of the phrases seem to be colloquial expressions or words while others are personal revelations and dream scenes. How do you choose the words and phrases? What was this selection process like?

I’ve always had notebooks, I’ve always written and drawn at the same time. Without being something I worried about all that much, the words emerged along with drawings. The drawn word, or the written drawing. The two things were never far removed. I never wrote a text from start to finish, with a beginning, middle, and end. My writings help me situate myself in time. Sometimes I stick a word from a book on top of an image and with that alone, I tell an entire story. I am in the habit of always having these notebooks in my arms. I am always ready so that I don’t simply let things pass me by and fly away. I note down my dreams, conversation from the back of the bus, an idea for the next project . . . and in my studio I look, reread, separate phrases, rewrite, and think about how I could materialize it into a project, unite the texts from the notebooks with the sewing machine—the machine—sewing the texts. And they remain there, engraved in the fabric forever and always. The word textile comes from the Latin “textus,” which means tecer, “to weave,” or “to interlace something with threads.”

The pieces in the series Costuras em feltro (Stitches on Felt) present notebook pages sewn onto felt. Margins and lines become a sequence full of movement and subtlety. Lines curve and reconstruct the topography of the page itself. Words are constructed out of different shapes. What does the transformation of the surface of those words represent? Why those words?

The lines in a notebook, in general, have a clear utility: to organize the text, to make the text comprehensible with a clear and sequential reading. I’ve never really followed that rule, but I always opted for notebooks with ruled pages. I discovered after some time that what attracted me to this choice was not having a blank page waiting for me. The lines were already a design. As time went by, I realized that the organizational forms of the world interest me. And I realized that there was a similarity between ruled lines and the coordinates of a map. Both have latitude and longitude. One organizes a text and the other organizes space.

The sensation that I had with this project was the same that I had with my notebooks. My own world kept safe between the pages. Everything I had lived. How many stories fit inside a notebook? How many stories can be written on the blank pages? An entire world awaiting the next word.

Are there any specific works that sparked your interest in studying and producing art?

I’m not sure I can say if there was a specific work, but before I began at the School of Arts, when I was seventeen, I went to a Leonilson exhibition. I met his sister, Nicinha, there. After seeing the exhibition, I told her I had really liked it and that I would look at those works every day as soon as I woke up. She asked me if I would like to visit the Fundação Leonilson (the house where they grew up and the organization that takes care of his estate). The next day I went and the following day I started working there. I helped with the cataloguing of his work. Looking at the drawings, separating them by techniques, years, dimensions, photographing . . . There, I came into contact with a huge part of his collection. I immersed myself in this intimacy, in the notebooks, tickets, cards, objects that he had in his room, and with his family. I came more deeply into contact with that which only the image tells us. I identified with that way of talking about yourself, through materials, colors, and words. It was all very simple and extremely profound.

What from your daily life is material for your creative process?

It is a constant state of attention. When I teach, I pay attention to the children’s movements, to how they begin and finish a drawing. When I’m walking down the street, I look at the nooks, at the ground, at the trash. When I dream, I pay attention to the images and absurd situations that I create. When it’s cold and I get a little warm, I think about the fabric on my skin. When I fall in love, when a relationship ends, when I organize the clothes on the clothesline by color, when I’m waiting for the bus—it is quite intense. I go a little crazy with so many images, so many feelings. I think to myself that everything could be potential material to be transformed. Every single thing, when taken seriously, is transformed and becomes eternal. It’s not that this is what always happens, on the contrary, those are rare and magical moments.

Do you think that aspects of your personality are reflected in your work? If so, which ones?

Yes, I believe my work has some things that I see in common with my personality. It’s difficult to explain, but it has to do with a contradiction between heaviness and lightness. Drama and humor.

Everything is very light and heavy at the same time, like the loose cloth on paper that is then pressed onto tons of series Monotipias (Monotypes). The result is something subtle, with transparencies and lightness. But what isn’t seen in this process is the weight and dirtiness that this cloth bore. I also see that there is a specific way of dealing with humor. A sad and gestural humor that is manifested through the material.

If you had the opportunity to invite one artist to dinner, living or dead, whom would you invite?

Choosing one artist is a bit cruel. I’m going to break your rules and invite more people to that dinner. I would invite Gertrude Stein, so she could tell me stories; Mira Schendel, since I couldn’t pass up that opportunity; and certainly Itamar Assumpção, so he could play all night long.