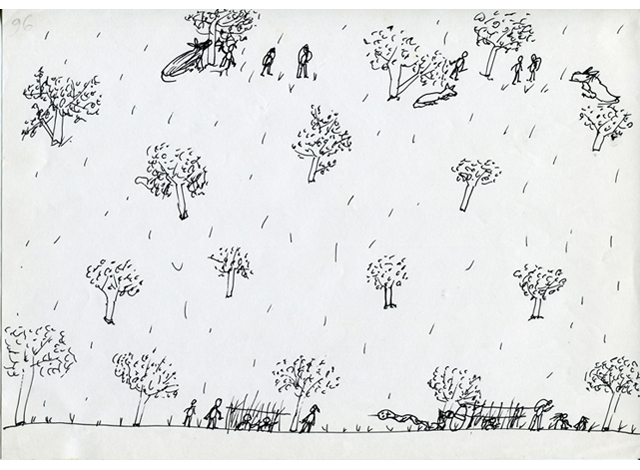

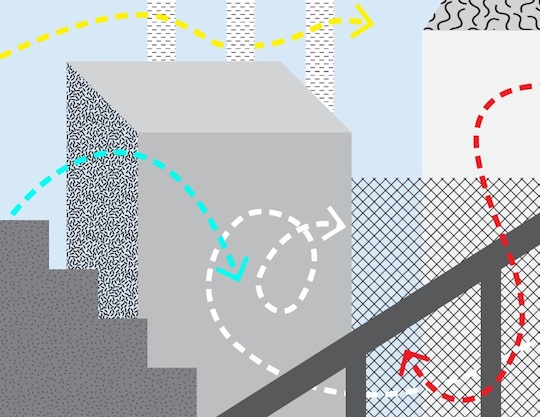

I’ve been living with Lata since the beginning of the summer. It’s true that I’m only fifteen and she’s around the same age, that we don’t have a single thing to call our own yet—no money, no nothing—but what’s the big deal? Lata and I, we know how to make things work no matter what. We haven’t found a long-term place yet, that’s true, too. We’re usually all over the map—on rooftops, in warehouses—but not every day of the week because we go back home often. I go to my mom’s and she goes to hers. She’s the one that really makes a scene, screaming and crying and saying a whole bunch of things I can’t understand. Of course, she always ends up cooling it and putting her arms around Lata; once she starts in with her broken Greek, everything goes back to normal. My mom, on the other hand, cooks dinner whether I’m there or not in the evening, and waits for me to show up with my stories about the outside world. It’s hard out there, I tell her, the old buildings are really tough and they chase us away. Her eyes open wide and she gives me a strange look. They put up scarecrows and wooden signs on the rooftops, as if we were unwanted birds, and if, after all this, we don’t heed their warning and lie down to sleep up there, there’s always someone who busts in and breaks it up with a gunshot in the air. On the other hand, you’ve got to have real balls to vault the obstacles on those new places, they’re super difficult, and they too want us out of there. I show her with my hands how you’re supposed to do the moves, how to jump over obstacles rhythmically, one-by-one. Like a primitive beast lost in the crowds of civilization, a mad rabbit let loose in the megalopolis. My body taut, my calves like stone, my lungs full of grimy air: that’s how I make it through the heart of the storm, see? That’s how the mind opens when you jump into space, how your thoughts breathe in oxygen. She starts yelling at me about how if I don’t shape up and get it together I will never find a job, about how I’ll get killed one day—all the usual babble. Don’t shout, I tell her, you don’t know what you’re talking about. How could you? Don’t worry—there’s no reason to. Everything will be fine: you see me now, there’s no obstacle anywhere that scares me anymore. And you know what, I like living like this; I like having you and Lata; I like walking on air. And if anyone asks me, I’ll tell them straight to their face: I don’t want to change anything at all, I want to stay like this forever.

READ MORE…