The annual Words Without Borders gala celebrated the fifth anniversary of the Ottaway Award for the Promotion of International Literature on November 1, named for the first chair of the board, Jim Ottaway. This year, the award honored Jill Schoolman, publisher of Archipelago Books. Archipelago has been a stalwart of the small but dedicated cohort of advocates for international literature in the U.S. since Jill founded the house in 2003—the same year Words Without Borders was created. In her humble, sincere acceptance speech, she told the room full of publishers, writers, translators, educators, and philanthropists, “I’ve felt a special kinship with WWB from the beginning. We created ourselves around the same time for many of the same reasons… Books that Archipelago publishes allow us to lose ourselves in other cultures and explore other worlds. It is our extraordinary translators who guide us through those worlds. We are extremely lucky to be working with such talented translators who are able to make books come alive for us, in both language and spirit. This wonderful award also belongs to them, too.”

Posts filed under 'self-translation'

Jill Schoolman Honored at the Glamorous WWB Gala

Young people are being told that America comes first. I think we are here tonight because we believe otherwise and because we read otherwise.

Self-Translation and the Multilingual Writer

The act of self-translation is for many, including Beckett himself, an experiment in agony.

Samuel Beckett self-translated a great many of his texts from French to English and vice-versa, and does not seem to have unequivocally favored one language over the other. For Beckett, choosing to write in French came from “un désir de m’appauvrir encore plus” (a desire to impoverish myself even further). Evidently, he viewed French as a more minimal language.[1] Beckett sparsely commented on his decision―or compulsion―to write in both languages, but in all events, such choices appear to be largely affective and difficult to justify rationally. All the more so when the act of self-translation is for many, including Beckett himself, an experiment in agony. For a minority, self-translation instead liberates the writer, at once from the risk of servility to an original, and from the effort of wrenching a brand new work from one’s mental background noise. One need neither give birth to a new text, nor obey an existing one.

The late novelist Raymond Federman, an émigré from France and a bilingual speaker, offers an example of one writer for whom self-translation was in some sense liberating. Federman wrote for several decades almost entirely in English, and only began to self-translate well into the middle of his career. In fact, English remained his dominant language of initial composition, and he once expressed to me a certain resistance to writing directly in French. Nonetheless, he self-translated extensively from the mid-nineties until his death in 2009. Federman introduces extensive and significant variations between translations and originals, so that his texts exhibit what Sara Kippur calls mouvance (variance), a term borrowed from medievalist Paul Zumthor.[2] Beckett’s own texts exhibit some variation, but in Federman’s case, narrative accounts of a single autobiographical event differ between accounts, whether they occur in different books or in the “same” book’s French and English version. Hence, Federman ties the act of translation directly to issues of autobiographical authenticity, demonstrating that such authenticity is largely illusory―memory is a kind of fiction.

Translating the Literatures of Smaller European Nations

Translators and scholars discuss stereotyping, globalization, and small sales in English-language literary markets.

Last September, three British universities—Bristol, Cardiff and UCL London—launched a two-year-long project on “Translating the Literatures of Smaller European Nations” in partnership with Literature Across Frontiers. The purpose was to “understand better the ways in which, through translation, these literatures endeavour to reach the cultural mainstream.” In addition to scholarly research, the project involves three public workshops and a conference.

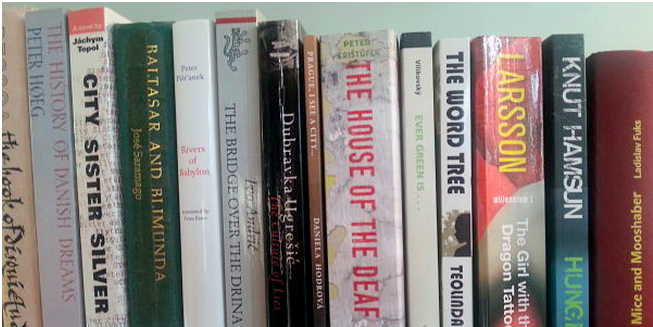

The first of these workshops, held in February 2015 in Bath, explored the question of “Who Reads the Literatures of Small Nations and Why?”. I had the pleasure of attending the second workshop, “Choreography of Translation,” which took place at the British Library in London as part of the European Literature Night in April 2015 (a third and final workshop, on promoting literature in translation, is planned for early 2016). Featuring publishers Vladislav Bajac of Geopoetika in Belgrade, Susan Curtis-Kojakovic, founder of Istros Books, translator (and Asymptote Close Approximations nonfiction judge!) Margaret Jull Costa, and Nicole Witt of the Frankfurt Literary Agency Mertin, the BL event ended up being more panel discussion than workshop, partly because the venue was not particularly conducive to the workshop format.

By contrast, a conference at Bristol University on September 9-10 provided many opportunities for lively discussions. The participants were a perfect mix of literature and translation studies scholars and practising translators from across Europe, covering a range of smaller European literatures from Catalan to Turkish. I’ll try to highlight some of the major issues covered, divided into often overlapping categories.