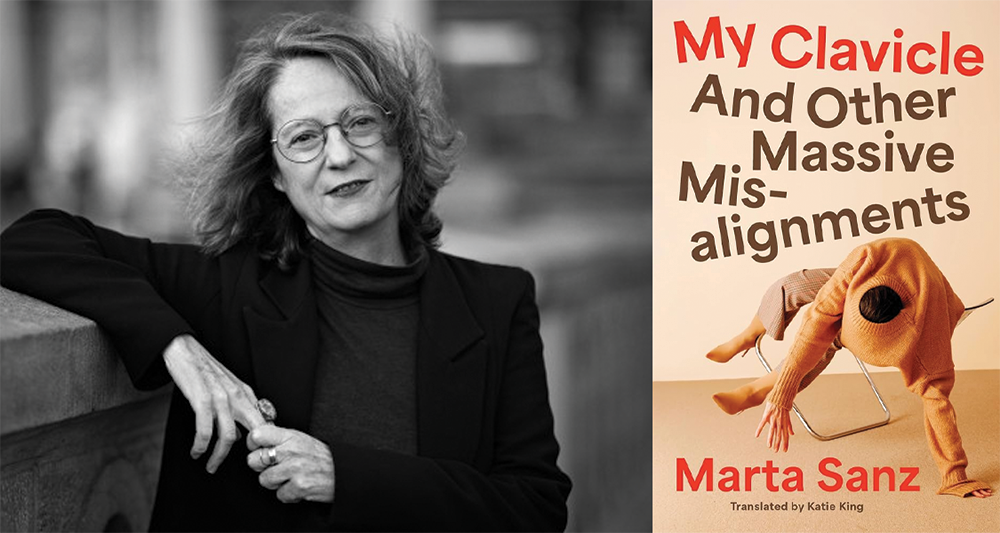

My Clavicle: And Other Massive Misalignments by Marta Sanz, translated from the Spanish by Katie King, Unnamed Press, 2025

In 2020, I was a postgraduate student amidst the COVID pandemic, writing my term-end assignment on Julia Kristeva and her concept of women’s time. Unwittingly, my professor had made a small typo in his materials; instead of ‘cyclical time’, he referred to the concept as ‘clinical time’. The term mystified us, and the entire class was held in a collective confusion in attempting to associate it with Kristeva. The error was later rectified, but not without arousing my interest; I was already thinking about the accidental ‘clinical time’, its importance magnified by the medicalised rhythm of the ongoing pandemic.

If Kristeva’s cyclical time is an indication of repetition and return, clinical time to me indicates a similar ebb and flow of a body in pain. Pain shapes time to be clinical; there is a surge and then a slump, affording the passing moments to be monitored and tracked and traded. In retrospect, the professorial mistake was actually a serendipitous slip that had already begun to align with my understanding of the physical world, an elucidation that was magnified when I encountered Marta Sanz’s My Clavicle: And Other Massive Misalignments. It was as if the error had already prepared me to read her work with a newer focus: to think of pain as a symptom as well as a diagnosis of misalignment, both physical and societal. READ MORE…