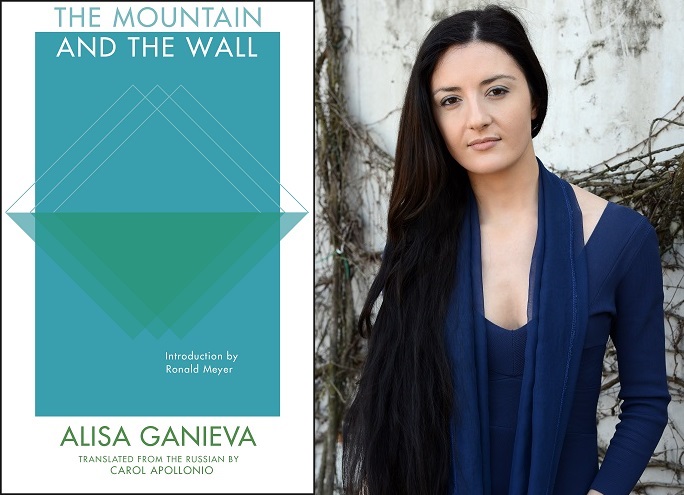

Carol Apollonio translated the first Dagestani novel available in English, The Mountain and the Wall by Alisa Ganieva. Anglophone readers will find much to relate to in the novel’s premise—a rumor that the Russian government is building a wall between the Muslim provinces of the Caucasus and the rest of Russia. In this free-wheeling, clear-eyed interview with Hannah Weber, Apollonio takes an impassioned look at literatures in translation, and at the simplest yet most complex human propensity—the desire to read.

Hannah Weber (HW): You’re a scholar of Russian literature and translate works from both Russian and Japanese. What led to your interest in these particular languages?

Carol Apollonio (CA): Most of your life path is luck. I knew early on that learning languages came easy to me, so I kept on doing it. After French, it was quite a shock to realize that for Russian you didn’t just plug the words into grammar you already knew. You had to change everything around in your brain. Plus, all the words were different. Anyway, if you’re rebellious enough, you decide it’s worth putting in the effort. It helped that I’d studied some Latin early on.

So, why Russian? Here’s how a Cold War eighteen-year-old radical hippie thinks in 1973: “The Russians are our enemies; the only problem is that Americans don’t know Russian. I’ll learn Russian, become president of the USA, we’ll all learn to love one another, and that will solve the whole problem.” So, I went to college and studied Russian and politics. As it turned out, I was too impatient and tactless for politics. As for Russian, at that time basically there were three paths for Russian-language students: one, learn about the complicated grammar and crazy vocabulary—recoil, and turn to economics or psychology; two, learn the language, recoil from the politics, and go into national security; three, learn the language, love it, read the literature and have your head explode. I’m one of the survivors with the exploded heads. READ MORE…