It’s the shortest month, but we’ve got quite the list. Our reviewers are taking you through eleven titles and ten countries: the latest novel from China’s most famous avant-gardist, a classic Tolstoy triptych of war’s ceaseless horror, a fictionalized memoir from one of Mexico’s greatest chroniclers of violence and legacy, a lyrical and lucid portrait of growing up in one of West Bengal’s riverside villages, and many more. . .

Gold Sand, Gold Water by Nalini Bera, translated from the Bengali by Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, Seagull Books, 2026

Review by Xiao Yue Shan

Despite all the battering that reality has historically taken under the wrath of language, with its voracious appetite for possession and imprisonment, there remain writers who seek to be more humane stewards, who want to take reality in and treat it with hospitality, patience, to let it roam free range. In Gold Sand, Gold Water, there it is alive, in all its shimmer and multiplicity, as disorderly and liquid as anything wild. Gaston Bachelard said it best in The Poetics of Space: ‘Man lives by images. . . . We sense little or no more action in grammatical derivations, deductions or inductions. . . . Only images can set verbs in motion again.’ Through a compelling delivery that melds this kineticism of portraiture with the haptics of linguistic texture, Nalini Bera brings a childhood, its legends and headwaters and music and verdure, downriver to us.

The river driving this episodic fiction is the Subarnarekha, flowing through the states of Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Odisha before entering the Indian Ocean. For Lolin, the young narrator of Gold Sand, Gold Water, it is a site of endless questions and unexpected encounters, joining history and the future, as familiar as home and as otherworldly as myth: ‘Not at its origin, not at its estuary, but at its mid-flow—at its mid-flow, someone threw a salver of gold into a river, and that river was named Subarnarekha—the golden streak.’ Something hypnotic enters the prose when the river does, bringing along with it a flurried litany of leaves, vines, snakes, fish, fragrances, people, emblems, ‘the hair of the Barojia maiden, Bhramar, wrapped in a betel leaf’. So too do the stories Lolin tell mimic this movement, which lithely go from a precise ethnography of this village that speaks a mix of Bangla and Odia, to episodes of mischievous boyhood, to the intimate goings-on of family and neighbours, to the intersections between nature and industry, to long-told tales of snakes that drink milk. It’s restless, just like the young boy behind the surges: ‘I often felt like following those who went westwards. They would reach their destinations, the villages they were headed to. But my journey wouldn’t end with theirs. I would just go on, and on, and on . . .’

Bera has a fondness for lists and names, and the pages are thick with transliterations (something that perhaps features in the original Bengali edition as well, which includes a glossary for the Odia words twinkling throughout the novel). It’s lovely to read these onomastic passages, in which nouns serve not only authority but also ornament, acting in the knowledge that a word is not only substance but also shape and music. (As per Auden: ‘Proper names are poetry in the raw.’) It also calls to mind the spatial demands that a name makes—its substantiation of presence—which both Bera and translator Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar must understand, for the dailiness and anciency of these riverside villages face extinction at the hands of both climate and modernity. As Bera writes: ‘. . . I was picking up seemingly useless things—like half a broken blade—from the ground and keeping them safe. Who knows what might be needed in the yajna?’ Perhaps a less sentimental writer wouldn’t have taken the time to list the growth along the banks—’trees like kendu, koim, bhela, kusum, doka, bhadu, karam, karanj, sal, piyasal and aasan; and bushes like aantari, churchu, chihar, kurchi, paraash, gabgubi and rangchita.’—but as we face a future full of disappearances, who knows what we might need?

The Enchanting Lives of Others by Can Xue, translated from the Chinese by Annelise Finegan, Yale University Press, 2026

Review by Eva Dunsky

The premise of Can Xue’s The Enchanting Lives of Others is likely to sound familiar to those who believe in literature’s instructive powers; its characters are members of the Pigeon Book Club, a group of literature enthusiasts who plumb the depths of books to find out how to live properly and with whom to fall in love. The first half of the novel focuses on Xiao Sang, Xiao Ma, and Han Ma, three women navigating the turmoil of their thirties: aging parents, murky romantic relationships, and the gap between their obligations and their passions. Xiao Sang, a department store clerk, lives far from home and interprets her life through the novels she reads; Xiao Ma, a straight-shooting romantic, has fallen for Xiao Sang’s older upstairs neighbor Uncle Yi; and Han Ma is the budding writer of the crew—with her talent and promise stemming from her fledgling marriage to Fei, a weak-willed man unable to make a final decision between staying with his wife or returning to Yue, his first love.

The second half focuses on Han Ma’s new relationship with Xiaoyue, another book club member who has always kindled a flame for her, waiting patiently as she sorts through the aftermath of her relationship with Fei by turning it into fiction. In some sense, this is a love story and marriage plot, though written in a metafictional mode, offering commentary on the endeavor of falling in love as an avid reader—which, as all readers know, will always be inflected by the literature we encounter.

Commenting on the novel, translator Annelise Finegan describes it as “conversational while both poetic and essayistic, and meant to leave room for the imagination, or what in Chinese aesthetics would be called liu bai 留白, leaving a blank or negative space.” This art of leaving space is rife throughout The Enchanting Lives of Others: gaps of understanding between lovers, an author and her public, the text itself and the multifaceted ways it might be understood. The question of how well you can really know another person can be troubling, as we’re only ever privy to our own perceptions—and this is especially true for avid readers who spend their leisure time parsing the behaviors of their favorite characters. Reading makes a person aware of how fickle and changeable human nature can be. As such, Can Xue has captured a peculiar conundrum of intimacy that all book lovers know well: that blurring of the lines between fiction and real life.

The Invisible Years by Rodrigo Hasbún, translated from the Spanish by Lily Meyer, Deep Vellum, 2026

Review by Eva Dunsky

Rodrigo Hasbún’s The Invisible Years centers around a single catastrophic high school party, the reverberations of which are still felt by two now-adult Bolivians living in Houston. Julián, a frustrated writer mining his life for material, tries to make sense of that night through the novel he’s writing, with hopes that doing so will relieve him of the guilt he still feels decades later. His novel-within-a-novel centers on two main characters: Ladislao, a seventeen-year-old caught up in a love affair with his American high school English teacher, and Andrea, his classmate, who finds herself in dire straits on the night she invites their senior class over for an unsupervised party.

Hasbún beautifully balances the universal aspects of late adolescence—that tentative step into adulthood amidst the lingering ephemera of childhood—and the specifics of this conservative, upper-class 1990s Bolivian milieu. By using Julián’s fictional novel as a frame, he also avoids the pitfall of a single answer to the tragedy of that night: Andrea’s ex-boyfriend’s rage, the abuse she suffers at his hands, her final fateful decision. In doing so, he refrains from spelling anything out for the reader.

When asked to comment on her experience translating the novel, Lily Meyer responded that what she loved most about The Invisible Years is its restraint: “Rodrigo has a very light touch, and in collaborating with him, I saw how thoughtful he is with every description, every clause, every bit of punctuation.” Indeed, this precision demands a lot from the reader—but offers a lot in return.

In Affections, Hasbún’s earlier novel, he takes a similarly fragmented approach to reconstructing the past, collating different points of view around a singular high-octane event or moment in history, which allows multiple truths to emerge. The Invisible Years reads like another iteration of that technique; in “pull[ing] back from the drama,” as Meyer puts it, he invites his reader to form their own theory of events—a distinctly individual truth, which becomes part of the novel’s chorus. Much like the clamor of reality itself.

White Nights by Urszula Honek, translated from the Polish by Kate Webster, Two Lines Press, 2026

Review by Mandy-Suzanne Wong

There is an acute, precarious restraint—through which extreme emotion sometimes slips, sometimes violently breaks—throughout Urszula Honek’s prose in White Nights, her acclaimed short-story collection translated by Kate Webster. “That morning, when there was no turning back, I thought about the relief of closing your eyes just once,” says the eponymous narrator of “Hanna.” The new day promises not hope but something dreadfully inexorable, and the sentence, like the day, does not unfold upon fresh opportunities but terminates in a dead end: “closing your eyes just once,” never to open them again. The “relief” of the fatal closing intimates the unuttered pain that suffuses the entire sentence.

White Nights squirms with such relentless, unspecified anguish. A festering horror hangs over Binarowa, the Polish village in which all the stories are set, lurking everywhere but impossible to pinpoint. This pervasive dread, which terrorizes without ever being described, manifests Honek and Webster’s rare prowess; theirs is a virtuosity of silence.

Nevertheless, this nameless torment has the capacity to shatter the remote farming village’s mundane quietude through acts of pointless cruelty. In Honek’s jarring juxtapositions of gentle, wistful images with brutal ones, fondness and nostalgia are obscene temptations that must be swiftly neutralized. “Just raise a foot in its old, battered shoe and stomp it down with full force,” says Henia in “Goodbye, It’s Over,” squashing a memory of love as though it were a poisonous insect.

Pregnant and deserted, Henia identifies strongly with the pig whom she fattens up and graphically kills. To be used up, drained of hope, and tempted by suicide is the fate of most of Honek’s characters. Their interconnected stories underscore their alienation from one another as intergenerational poverty and trauma encourage alcoholism, spousal abandonment, and fear of ostracism, causing trauma to be passed down along an expanding spiral.

Poland’s long history of being carved up, used up, and discarded is implicit in Honek’s allusions to the seventeenth-century Swedish Deluge and more recent German shootings. Mass graves and former extermination camps surround Binarowa, and the Allies’ abandonment of Poland to Stalin after WWII is a national trauma from which many rural areas have yet to recover economically or psychologically. As Honek’s stories suggest, these persistent hauntings intersect with contemporary issues like deficient healthcare and poor education, resulting in an awful silence within which echoes an unspoken but collective suspicion: that it is possible to be defeated by life before one even begins to live.

A Parish Chronicle by Halldór Laxness, translated from the Icelandic by Philip Roughton, Archipelago Books, 2026

Review by Eric Bies

When someone once recognized as the greatest in their field suffers a sudden, precipitous fall—that’s the so-called “Nobel Curse.” But it’s hardly the rule that winners should anguish; take Halldór Laxness. Iceland’s sole Nobel Laureate picked up the award in 1955, but his most remarkable novel—the marvelously strange, sui generis book that is Under the Glacier—didn’t appear until 1968.

It’s a similar story for A Parish Chronicle (an admittedly minor work by this major author), which originally came out in 1970 and is only now entering the English language thanks to Philip Roughton (whose previous Laxness translations include Salka Valka and Wayward Heroes). Yet another delightfully odd novel, A Parish Chronicle is representative in that it displays all the hallmarks of its author’s distinctive style. These include episodes of a surreality to rival the best of Kafka; a geologist’s fidelity to Iceland’s complicated landscape; and an ironic historical perspective that positions him as both his country’s greatest champion and its most savage critic.

In a little more than a hundred pages, the novel’s narrator (another of Laxness’s standbys, “the undersigned”) charts the life and times of a single building, an old church standing on a hill in Mosfell Valley, some twenty kilometers east of Reykjavík. To the extent that titles hint at the contents, A Parish Chronicle is largely what it sounds like: a record of the goings-on in and around that parish, beginning with the story of how the bones of “Iceland’s national hero and chief poet Egill Skallagrímsson” ended up buried under the altarpiece (“even though he had been a heathen”).

The book’s thoroughgoing sense of fun has everything to do with its narrative voice. Laxness is a natural when it comes to sounding like the local historian, with more anecdotes than sourcebooks. In the course of relating the history of the church and its environs, readers meet the structure’s staunchest defender (always ready for a fistfight); an industrious ash-shoveler sitting on an untapped fortune in geothermals; and a boy who dreams of breeding sharks in his father’s rain-barrel. However locally inspired, it’s the sense of ease and familiarity with which Laxness weaves his various narrative strands that lends the novel a timeless air, so much so that you wouldn’t be mistaken if you came away feeling like a cast of new myths has just taken shape before your eyes.

With The Heart of a Ghost by Lim Sunwoo, translated from the Korean by Chi-Young Kim, Unnamed Press, 2026

Review by Eva Dunsky

Lim Sunwoo’s With the Heart of a Ghost feels acutely observed and oddly realistic for a collection populated by mutant jellyfish and errant ghosts. The heartbreak and disillusionment of these stories often manifest literally—but in surreal and speculative ways. In “Summer, Like the Color of Water,” a jilted ex turns into a tree in the apartment of his ex-lover (much to the current tenant’s dismay). In “Curtain Call, Extra Inning, Last Pang,” the victim of a random and fatal accident spends her last day on Earth freeing the ghost of an aspiring K-pop star from the confines of the vacuum cleaner she’s been sucked into.

When asked about which aspects of the collection she connects with most, translator Chi-Young Kim responded: “Lim’s characters find moments of genuine connection . . . new connections, revived connections, connections with oneself. Much of the world feels bleak right now, and it’s lovely, even healing, to spend time with souls who are not only seeking human connection, but wanting something better.” And indeed, the joy of this collection lies within these intimately rendered connections: a man spiraling but then finding connection with an ex-lover after losing his pet gecko; two neighbors connecting through the power of their minds to bore holes through the walls of their apartment complex.

In Kim’s lucid style, even such speculative elements seem to be realistically documented. If phantoms and magic did exist on earth, these stories demonstrate how our connections with them might take place. Take “You’re Not Glowing,” a story about a plague of jellyfish that wash up on beaches and lure humans to touch their poison, which transforms them into mutant jellyfish themselves. Lim depicts a perfectly reasonable aftermath, which only emphasizes the satirical nature of what we consider normal:

A new jellyfish religion was formed.

People wanting to kill themselves traded jellyfish tentacles at a markup.

Criminal organizations embraced the use of jellyfish tentacles as a new lethal weapon.

A creepy rumor went around that these jellyfish were used to make cheap gummy snacks.

Chinese restaurants pulled cold jellyfish salad off their menus.

A cosmetics brand that advertised how their products would produce jellyfish-glass skin posted an insincere apology the next day.

Haven’t we encountered the rumor of the corrupted gummy snacks? Haven’t we heard that cosmetics brand’s apology? While the collection is heavily metaphorical, the prose never feels heavy-handed. Instead, Lim’s strange, charming constructs feel like necessary conceits for describing the particular plagues of modern life.

Pedro the Vast by Simón López Trujillo, translated from the Spanish by Robin Myers, Scribe, 2026

Review by Eva Dunsky

What happens when the forests we indiscriminately decimate and harvest start to decimate and harvest us back? In Simón López Trujillo’s Pedro the Vast, the titular patriarch of a family ravaged by poverty and isolation falls ill with a mysterious cough. When four of his coworkers die in rapid succession, Pedro is left as the sole survivor of this plague. Laid up in a hospital, he’s diagnosed with a novel fungal infection caused by the Cryptococcus gatti mushroom, which causes mycelium growth to colonize and ultimately take over the body.

Both scientists and acolytes quickly descend on the local Chilean hospital where Pedro is being kept. Giovanna, a researcher with an interest in fungal properties, makes the pilgrimage to the extreme south of Chile with a cadre of other biologists and mycologists, while Balthasar, a local priest, builds a ministry of congregants around Pedro’s increasingly erratic mycelium-fueled outbursts. In their dichotomous approach, the novel can be read as commenting on the limits of both science and religion, as neither is able to capture or elucidate the terrifying potential of nature itself. Both forces—Giovanna’s scientific crew and Balthsar’s ministry of worshippers—fail to contend with Pedro’s illness, and we’re left to assume that as the infection spreads, they’ll ultimately meet his same fate.

Once the mycelium fully colonizes Pedro’s body, the Cryptococcus gatti mushroom does away with Pedro’s previous subjectivity, returning him to the expansive multi-consciousness of the forest’s network. As he begins preaching a doctrine of multiplicity and takes on his spiritual name of Pedro the Vast, the novel almost veers into a fable of relative equilibrium: Pedro’s body being returned to the earth from whence it came. However, his children—an eight-year-old named Cata and a teenager named Patricio—serve as complicating human factors. Patricio, suffering all the myopia and emotion of adolescence, is in no way ready to become his sister’s caretaker, and together they struggle as their father’s income dissipates and they gradually run out of food and fresh water. Their struggle makes clear that any return to the logic of nature will not be a peaceful occurrence; it’ll be a seismic upheaval, both bloody and painful.

But not impossible. Perhaps even inevitable. Because our sins—our avarice, our overconsumption, our lack of regard for fellow living things—exist only so long as the sinner and sin are separate entities. As Pedro the Vast preaches:

If one must sin, then let him sin while thinking of God. You are the sin. I am the sin. But if we returned to our place among the muchness, all and both in myriads, in what we once were, then no sin could be committed, nor coldness, nor sundering lies.

Autobiography of Cotton by Cristina Rivera Garza, translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney, Graywolf Press, 2026

Review by Mandy-Suzanne Wong

Only a writer as versatile as Cristina Rivera Garza could manage such a vast, multitemporal project as her latest novel, Autobiography of Cotton. Her successes in many genres—from journalism to dark speculative fiction—give momentum to this grand and intimate collage, the elements of which readers are tacitly invited to collate into a story. It also happens to be a true story, speculatively told in all its open-ended nonlinearity.

Autobiography of Cotton begins by summoning all the senses to “the light of an intransigent sun . . . the pinkish, gray, and cinnamon-colored dust” of Anáhuac in northern Mexico, where both Rivera Garza’s grandfather, a cotton worker, and the communist activist José Revueltas happened to be in 1934. In tender, vivid third-person prose, Rivera Garza imagines noncontiguous scenes that could have led up to a meeting between the two: intimate talks between her grandparents in their adobe thatch-roofed house; Revueltas and a typewriter taking dictation from the workers. . . After all, Garza writes, “Memory is pure fiction.”

But this novel is not “pure” fiction. Indeed, by juxtaposing fiction with historical research and cultural analysis, and switching styles in response to shifts in content, Rivera Garza suggests that “purity” exists in neither fiction nor memory, and she emphasizes the latter in her first-person recollections of Autobiography’s traumatizing research process. In the aftermath of foiled attempts to visit the “disappeared” towns where cotton workers once resided, Rivera Garza struggles to come to terms with her discoveries; official claims that her grandfather “abducted” her grandmother plunge the author into survivor’s guilt, which tempts her to blame her ancestors for her sister’s murder.

Scattered throughout the book, a small archive of reproductions (letters to higher-ups, an irrigation-district map, Rivera Garza’s grandmother’s US-immigration “card manifest”) shows the scant attention paid to cotton workers by official history. It was Revueltas who, in his novel Human Mourning, became the first to document the construction and failure of Anáhuac’s dam and cotton fields, as well as the cotton workers’ 1934 strike.

Thus, Rivera Garza writes, “Attention can be a way of doing politics at times.” In analyzing Revueltas’s work and its extension of communistic equality to non-humans, she brings him into conversation with such new-materialist forerunners as Gilles Deleuze and Jussi Parikka, thereby joining her own ancestral story to ongoing ecocritical discussions.

Each writerly approach—through memoir, fiction, scholarship, or archive—generates gaps in the story at the heart of Autobiography of Cotton. Yet it is the gaps that constitute the novel’s truth and motivation. It is the silences of the cotton plants, which mark every body in and after Anáhuac. It is the silences of the dead. The resultant book is more of a process than a product, an ongoing migration between ways of thinking, turning genre into hypothesis. As resolute as ever, Rivera Garza tests each method of writing, remembering, and storytelling by encouraging its inherent incompleteness—and thus its inevitable brokenness.

The Roof Beneath Their Feet by Geetanjali Shree, translated from the Hindi by Rahul Soni, And Other Stories, 2026

Review by Mandy-Suzanne Wong

The heart of the world is infinite in Geetanjali Shree’s novels; every feeling is as keen and bright as joy, and joy is everywhere, awaiting discovery. In The Roof Beneath Their Feet, wherein the rooftops of a neighborhood form a landscape of leaping summits and valleys, the throb of life shimmers in all things—especially the roof itself. “A roof of wonders, a roof for all seasons. A roof that fostered all relations, a roof free from all pressures. A roof leaping from infinity to infinity.” As the narrator, Bitva (a general term of endearment for small boys), recalls: “It was the roof perhaps that kicked our dreams up high with a kick of love.”

The roof is a safe space for women, children, lovers, and exhausted workers on summer nights, and it is there that Bitva’s conservative Chachcho (Auntie) forges a lifelong friendship with Lalna (Darling), a free-spirited woman of a lower class and dubious history. On the roof, Chachcho and Lalna share secrets and sing songs barefoot as the neighborhood condemns their relationship, and even Bitva is envious and suspicious of their bond.

Throughout the novel, the roof guides the reader between flipsides of experience: reality and possibility, memory and forgetting, death and life—“And isn’t laughter a way of crying?” In Shree’s books, thresholds are figures for latent dualities; a private home is simultaneously a public, political realm, and the insider becomes an outsider with but a turn of a door. Lalna is scorned below the roof but cherished atop it, where her and Chachcho’s intimate friendship elides her public ostracism.

Shree’s irresistible prose dances with a marvelous sonority and rhythmic sway. Indeed, her playful musicality is a top priority for translator Rahul Soni, and the resultant sense of language alive and dancing brings a sparkling intensity to Shree’s big-hearted thinking; just as nothing is excluded from the community of living things, no relationship precludes love. “Love isn’t what you all think it is—man and woman and woman and man and bodies, bodies, bodies!” Lalna says. Rather:

. . . when the sky starts turning around the axis of the roof, then no one can stop two friends, nothing can erase them. Our hearts jump into our mouths and a flame starts dancing in front of us. . . .

The two of us would go to the roof again and again. Not to meet anyone else, but to meet that flame.

Sevastopol Tales by Leo Tolstoy translated from the Russian by Nicolas Pasternak Slater, Pushkin Press, 2026

Review by Eric Bies

From October 1854 to September of the following year, the city of Sevastopol was the site of a siege comparable to an interminable rain—if the raindrops were bombs. Then the city fell, and as the ruined Russian army retreated by foot (their navy’s legendary Black Sea Fleet having been reduced to tatters), all of London was alive with the news of victory. Tennyson’s “Charge of the Light Brigade,” with its sham sense of wartime glories, had been easy enough to memorize. But for those who’d actually been there, who had stalked the muddy trenches and dodged the shrapnel themselves, war was hell and little more.

Few could articulate that fact with as much vitality or accuracy as a young, wispily mustachioed Leo Tolstoy, whose service as an artillery officer amply furnished him with the material to write his Sevastopol Tales, the book that made him a household name in nineteenth-century Russia. In the course of scarcely two hundred pages, the future author of War and Peace explicated, in vivid Russian prose, the same themes Wilfred Owen would elaborate, in unvarnished English verse, some sixty-five years hence: there is nothing sweet or proper about dying for one’s country.

The three stories of Sevastopol Tales form an unsparing triptych of gritty realism, each panel centering on some form of suffering inflicted by war. But it isn’t just the overabundance of faithfully rendered grimness that makes these sketches so memorable (not to mention so eminently worth returning to in their latest iteration, a stupendously readable English translation by Nicolas Pasternak Slater); Tolstoy’s grand, cinematic style is evident here in embryo, in comparative miniature, flashing through a somewhat predictable yet distinctive set of types, from the would-be hero and the coward to the idler and the braggart.

The book’s clipped chronology hops from December through May to conclude in humid August, mere days before the end of the Allied siege. Across that desperate span is splayed a series of dramas: poignancy dukes it out with despair; the narrative trajectories almost rewarding expectation just before subverting it; tones rotating from the horrible to the humorous to the heartrending and back. It should come as no surprise that the loss of precious life figures prominently throughout, but few specimens of the genre can match the enduring power of the Tales’ concluding “Sevastopol in August 1855,” in which the tragic story of the Kozeltsov brothers is a knife in the belly, haunting and almost viciously indelible.

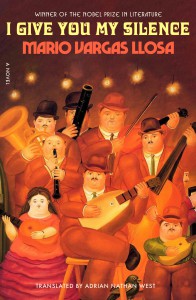

I Give You My Silence by Mario Vargas Llosa, translated from the Spanish by Adrian Nathan West, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2026

Review by Eva Dunsky

In I Give You My Silence, Mario Vargas Llosa provides a sweeping account of Peruvian criollo music and its intersection with the country’s body politic. His protagonist, Toño Azpilcueta, is a teacher by trade and music journalist/aficionado by higher calling, one-half of Peru’s many middle-class couples pooling their meager salary and barely scraping by.

Toño has long suspected that criollo music—a mixture of European imports and indigenous sounds—serves as the distinguishing factor that sets Peru apart from its neighbors, and after attending a concert given by the virtually unknown guitarist Lalo Malfino one evening, Toño resolves to explore the balance between the man’s talent and his short and tragic life. Soon, a history of the country and its music takes hold in his mind, and he resolves to put it all down in a book. His thesis is simple: “People tend[ed] to take religion, language, or wars as the constituent elements of a country, a society’s fundamental realities; it had occurred to no one that a song or music could stand in for these.”

It’s a lofty idea that receives mixed reviews, but Toño is insistent; as he descends deeper into his investigation of Lalo Malfino’s life—which expands to encompass the history of Peru—he remains steadfast in his belief that the blended cultures of this music alone can unite the country’s stratified social classes. Throughout the novel, Vargas Llosa compounds this theory with paragraphs on music history, seemingly taken from his protagonist’s ongoing manuscript: “No sooner had the creole vals appeared—and this says something about how quickly it spread through all the social classes in Peru—than young men of good breeding and bad habits began to frequent the alleyways in the working-class neighborhoods where valses played and parties went on for days on end with abundant singing and dancing.”

By the end of the book—both the one Toño is writing and I Give You My Silence—the reader has been divested of some (but not all) of their lofty ideals on music’s unifying power; there are systemic issues plaguing Peru that are surely beyond music’s power to fix. Still, art remains a powerful agent of social cohesion, so this disillusionment is not total. Perhaps the author didn’t want to leave his readers too disenchanted, for in one of the novel’s more metafictional moments, Vargas Llosa asks that we read his protagonist as a stand-in for himself: an old man looking back at his legacy and the trajectory of his country. Having known that this book would be his last, the author assigns his final words to Peru’s complexity—and its glory.

Eric Bies is a high school English teacher. His writing has appeared in World Literature Today, Rain Taxi, Full Stop, Open Letters Review, and many other places. He lives in Southern California.

Eva Dunsky is a writer, teacher, and translator. Her fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Joyland, The Los Angeles Review, The Rumpus, Bookforum, and Pigeon Pages, among others, and she’s at work on a novel. Read more of her writing here.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet, writer, editor, and translator.

Mandy-Suzanne Wong writes experimental fiction, essays, and poetry. Her books include The Box and Daughter of Mother-of-Pearl, both published by Graywolf Press.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: