Since its conception nearly twenty years ago, the Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation has sought to bring a wider scope of attention and celebration to works translated into English from the Arabic, resulting in a plethora of incredible titles being honored over the years, from the 2008 awarding of Mahmoud Darwish’s The Butterfly’s Burden, translated by Fady Joudah, to the 2019 awarding of Khaled Khalifa’s Death is Hard Work, translated by Leri Price. In this essay, Ibrahim Fawzy takes us across the most recent shortlist and its six works, discussing their distinct contributions to the Arab world’s abundant archive.

Contemporary Arabic literature offers rich, varied responses to the shared human experiences of displacement, conflict, and the weight of history. With its compelling and diverse array, the shortlist of the Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation presents a brilliant selection of such works each year, spanning genres from memoir to thriller, and reflecting the vitality and range of modern Arabic literary expression. In the 2024 prize, the six works on the shortlist—brought into English by dedicated translators—offer profound insights into the complexities of identity, memory, and resilience. While the judges ultimately awarded the prize to Katharine Halls’s translation of Ahmed Naji’s Rotten Evidence early this year, every shortlisted text invited comparative reflection on how these distinct narratives converge around the very act of bearing witness.

A prominent thread running through these works is the engagement with historical and political trauma and its lingering aftershocks, with which Rotten Evidence provides a stark, intimate account of censorship, as well as a commentary on the absurdities and brutalities of Egypt’s carceral state. The Acclaimed Egyptian novelist and journalist Ahmed Naji was imprisoned in 2016 under the regime of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, after an excerpt from his novel Using Life was published in the literary magazine Akhbar al-Adab. The piece, which included descriptions of sex and drug use, led to a public morality lawsuit, filed by a sixty-five-year-old reader who claimed it caused him physical distress; Naji was charged with “violating public decency” and sentenced to two years, of which he served nearly ten months in Tura Agricultural Prison before his sentence was suspended. Rotten Evidence, written in the aftermath of Naji’s incarceration, is a prison memoir that uncovers the corrosive psychological toll of confinement, the fading of memory, and the struggle to maintain one’s sanity and identity. Immersing the reader in the lived reality of state power, Naji reveals the dehumanizing effects of authoritarian systems through his interactions with indifferent guards, dismissive officers, and opaque bureaucracy. Within such an oppressive environment, writing becomes a mechanism of survival and an assertion of self and intellect in the face of institutional erasure. “Keeping a diary is a survival mechanism,” writes Naji, “It stops me from being swept away in the current that is the peculiar rhythm . . . of prison life.”

A different form of trauma, displacement, and the erosion of identity anchors Huzama Habayeb’s Before the Queen Falls Asleep, translated by Kay Heikkinen. Framed as a mother’s story to her daughter, the novel traces decades of upheaval, beginning with a forced departure from Kuwait during the 1990 Gulf War. Memory takes center stage in this novel as well. Through recollection and storytelling, the protagonist safeguards her family history and maintains a sense of rootedness while navigating life in “homelands that belong to others,” as the author puts it. Unlike the raw immediacy of Naji’s prison memoir, Habayeb’s work uses personal and familial memory as a bulwark against forgetting, preserving stories of community, rebellion, and endurance. In an interview, the author describes her novel as the reverse of Ghassan Kanafani’s lauded novella, Men in the Sun (translated by Hilary Kilpatrick); where that narration is of three Palestinian refugees crossing the desert to Kuwait, Before the Queen Falls Asleep, conversely, tells the story of Palestinians escaping Kuwait. Unlike Kanafani’s cinematic style, Habayeb’s prose is lyrical and deliberately unhurried, compelling the reader to dwell in the discomfort alongside her characters while bearing witness to their endurance and unraveling. In describing the separation from a loved one, she movingly writes: “I swallowed the sobs rising urgently from the heap of bitterness accumulated in the valley of my soul. I strangled them before they reached my throat, which I constricted violently. But I could not strangle my tears. They flowed densely and slowly, thick and freighted with sadness unrelieved by any hint of joy, sadness of the kind that turns into a permanent condition of daily life.”

In Lost in Mecca, translated by Nada Faris, Bothayna Al-Essa turns to the thriller genre to explore grief and inequality. The novel follows a frantic search for a missing child during the Hajj, which quickly reveals a dark underworld of criminality. Within Lost in Mecca’s medley of geographies, languages, and desires, readers hear the voices not only of those who have been marginalized in Mecca, but in surrounding cities and countries as well—children of unknown parentage living in camps, poverty-stricken individuals traversing the Sahara in search of a better life, those who have been trafficked or molested. With both compassion and a stoic eye on the world, the novel explores what motivates marginalized individuals to resort to criminal activities, compelling readers to question the circumstances that could cause them to disregard their own moral values. In effect, Lost in Mecca demonstrates how individual tragedy can illuminate broader societal dysfunctions and buried cruelties.

As samely as Al-Essa renders the streets of Mecca, Stella Gaitano’s Edo’s Souls, translated by Sawad Hussain, captures the neighborhoods of Khartoum, transcribing the relentless uncertainty of life shaped by violence and systemic marginalization. A multigenerational epic set against the backdrop of the sociopolitical upheavals in the 1970s, a period marked by growing unrest and unbalanced development, Edo’s Souls shines a light into the darkest corners of inhumanity and discrimination with remarkable subtlety and power. Rather than narrating history outright, the novel reveals it through intricately crafted scenes, nuanced details, and lyrical, intimate storytelling; the large-scale disruptions manifest in Edo’s repeated loss of children, her spiritual defiance against death, and her daughter’s eventual migration to Khartoum. Certain characters carry the scars of the 1955 massacres and the north-south divide, while others embody shifting values amid forced marriages and gendered oppression. In essence, history in the novel is not a public chronicle but a palimpsest of grief, myth, and survival, passed through women’s bodies and memories, lingering in gestures, names, and the spaces between life and death.

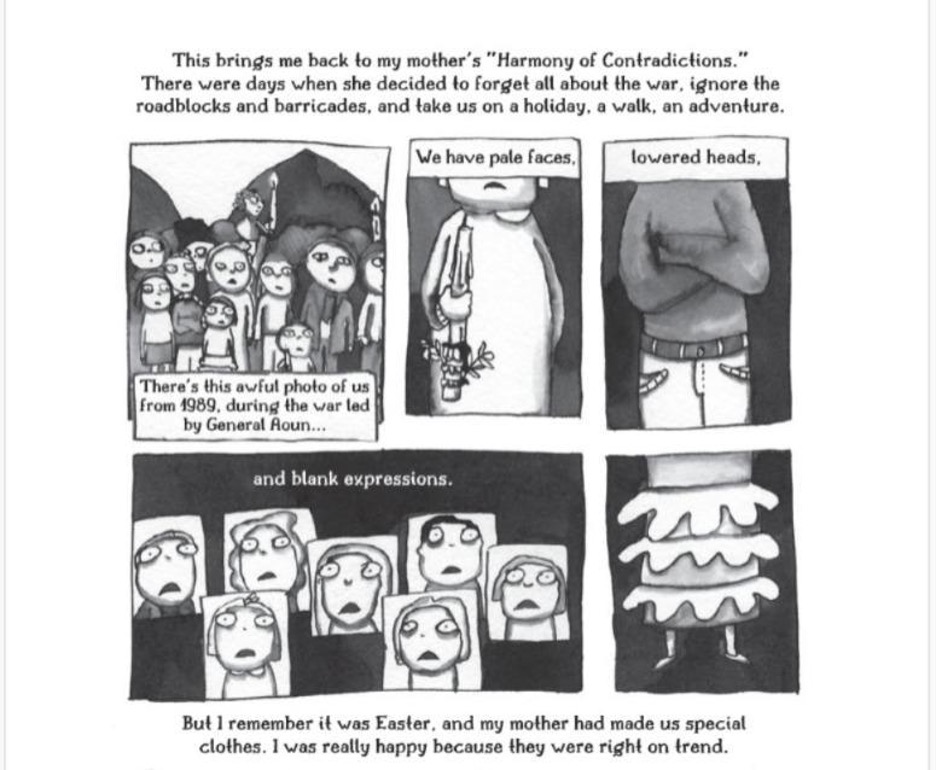

The shortlist’s most formally innovative work is Yoghurt and Jam (or How My Mother Became Lebanese), a graphic memoir by Lena Merhej, co-translated by Nadiyah Abdullatif and Anam Zafar. Melding a confessional writing style with intuitive, intimate illustrations, Yoghurt and Jam offers a fresh approach to intergenerational trauma as Merhej recounts her experience growing up in Lebanon amidst war, cultural tension, and maternal complexity. The graphic form allows for a layered exploration of memory, mixing humorous anecdotes, family quirks, and childhood impressions with moments of intense vulnerability. Through this format, Merhej emphasizes that even in times of violence; personal histories remain rich with contradiction, humor, and humanity. For instance, one of its scenes reveals the human instinct to preserve joy, even under siege:

Last but not least, Iman Mersal’s Traces of Enayat, translated by Robin Moger, functions as a biographical detective story, as Mersal seeks to reconstruct the life of the overlooked Egyptian writer Enayat al-Zayyat. After her only novel was rejected, al-Zayyat committed suicide, and Mersal’s work thus becomes an act of literary reclamation, recovering a silenced voice and examining the obstacles facing women writers in mid-twentieth-century Egypt. As attentive to the process of biography as it is to its subject, Traces of Enayat interweaves literary history, archival labor, and feminist inquiry into an engrossing meditation on absence, failure, and remembrance, resulting in a meditation on the act of the search, as well as on the ethical and emotional implications of writing about another woman’s silence and erasure.

Mersal’s journey is deeply reflective and recursive. “Was I running away, escaping my own life by chasing clues into the life of a woman who wrote a single novel and died before she could see it published?” she asks, in a moment of stark introspection, signaling her understanding of herself as implicated within the story’s tangled threads. As she travels through Cairo’s necropolises and dusty bureaucracies, it becomes clear that this pilgrimage is not just for Enayat; it is also an act of remembering for Mersal herself, a confrontation with the monsters of depression and erasure that haunt both women.

Collectively, these six translated works, representing a range of narrative forms and styles—from prison memoir and biographical investigation to graphic storytelling—demonstrate the formal innovation, thematic depth, and beauty of contemporary Arabic literature. They engage deeply with the enduring legacies of trauma, displacement, and conflict, exploring how memory shapes individual and collective identity, as well as the multifaceted ways people navigate and resist oppression, loss, and fragmentation. As translator Roger Allen notes, Arabic literature remains a “flyover zone” in Western publishing, often obscured by geopolitical reductionism or linguistic unfamiliarity. Far from presenting a unified image, these titles reflect the atomization of Arabic literature across geographies, genres, and politics, and by highlighting this multiplicity of Arabic narratives, the Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize disrupts monolithic representations, insisting instead on Arabic literature’s vitality and diversity.

Ibrahim Fawzy is Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: