Humans throughout history have been fascinated by the elements. Unfathomable forces of nature, they entered our myths and minds aeons ago. There’s no time when we’re not in their thrall. Drawing from the vast store of our collective imagination across mythology, philosophy, religion, literature, science, and art, I present Elementalia, a series of five element-bending lyric essays that explores their enchanting stories and their relationship with the word—making, translating, and transforming meaning and message. This is not an exhaustive (nor exhausting) effort that covers every instance of and interaction with each element, but rather an idiosyncratic, intertextual, meditative work—a patchwork quilt of conversations with other writers, works, and texts across space and time.

Inspire, from the Latin inspirare, in- + spirare, to breathe.

*

Winds in the east, mist comin’ in

Like somethin’ is brewin’, about to begin

Can’t put me finger on what lies in store,

But I feel what’s to happen all happened before– Bert, the chimney sweep, in Mary Poppins, 1964

A Western child may believe that a story lives in a book, ideally beautifully illustrated by someone like Arthur Rackham. In Indian folklore, a story lives inside the teller, literally, physically inside. And it is his or her duty to pass it on. If the teller fails to pass on this story to some listener, the story will take its revenge and she (it is almost certainly likely to be a woman) will suffer punishment.

– Girish Karnad, AK Ramanujan Memorial Lecture

Hold my head while you’re filling it with your lies.

– The jinni Dunia to her lover, the philosopher Ibn Rushd,

in The Duniazát by Salman Rushdie

*

प्राणायाम

prāṇāyāma

the expansion of the breath of life

*

INSTRUCTIONS FOR A NOVICE

do not breathe

a word

do not cast

into the wind with

almanac, birdseed, and cowrie

do not sing it to

the west, the south, the east,

and never ever the north

do not mark it, name it, tame

the named it, do not tug it on

its long leash, fight it,

delight it

should you find

a word, tuck it

quick in your cheek,

suck it, swallow it whole,

a siege, a sough,

a seethe

stir your sap with it,

set your bones with it,

smoke your skin with it,

shiver the air with it

trade the changeling,

no trick, no fuss, and for

fuck’s sake, never ever

cry

and whatever you do,

do not lie, but

if the word

must not find

you: do not

breathe

*

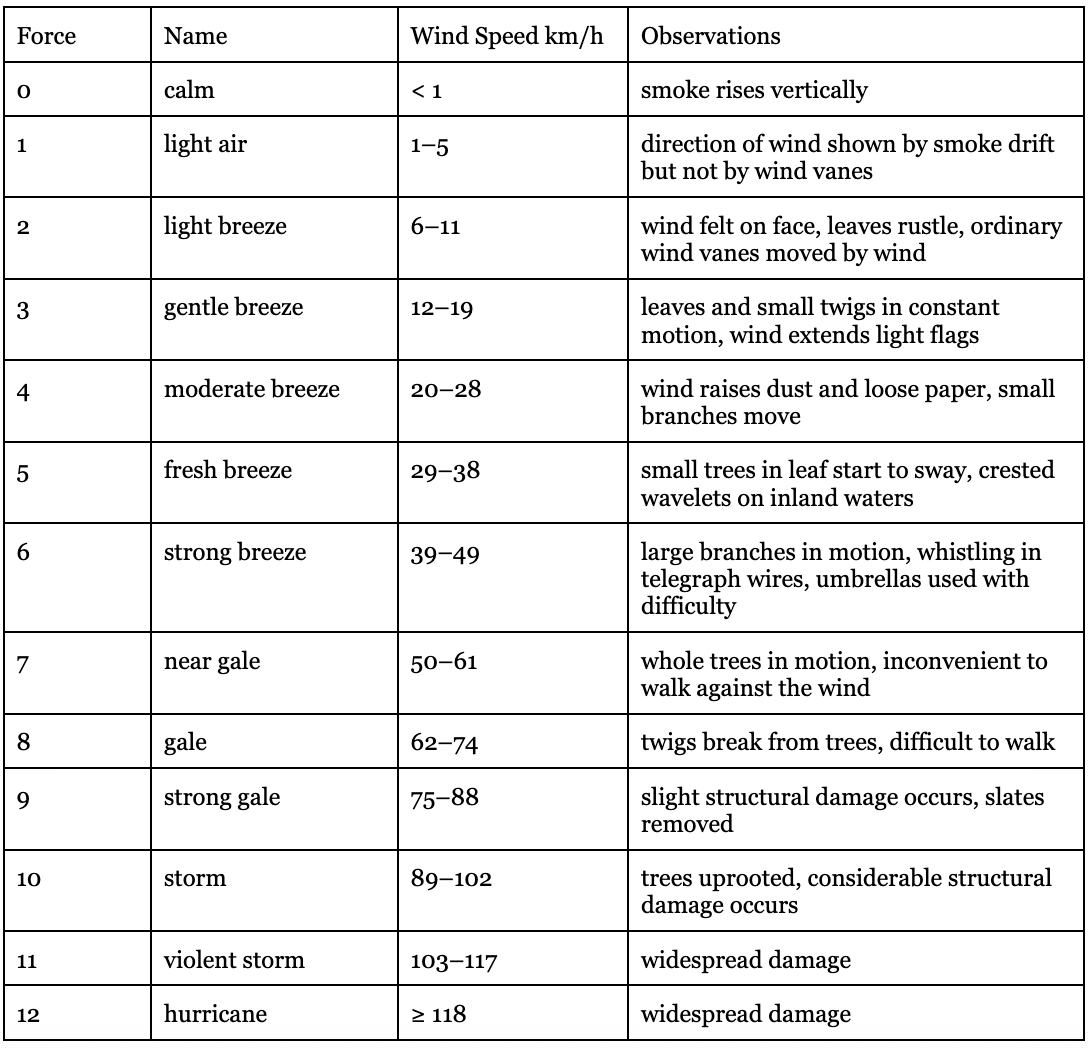

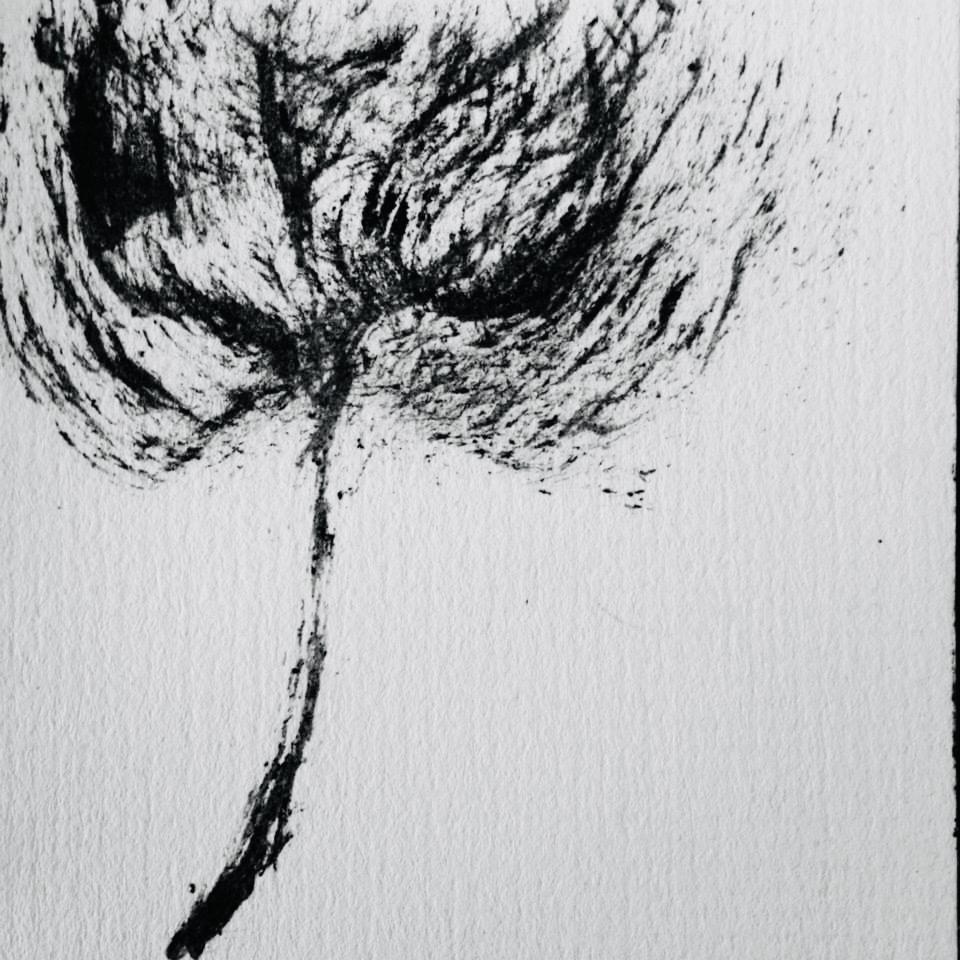

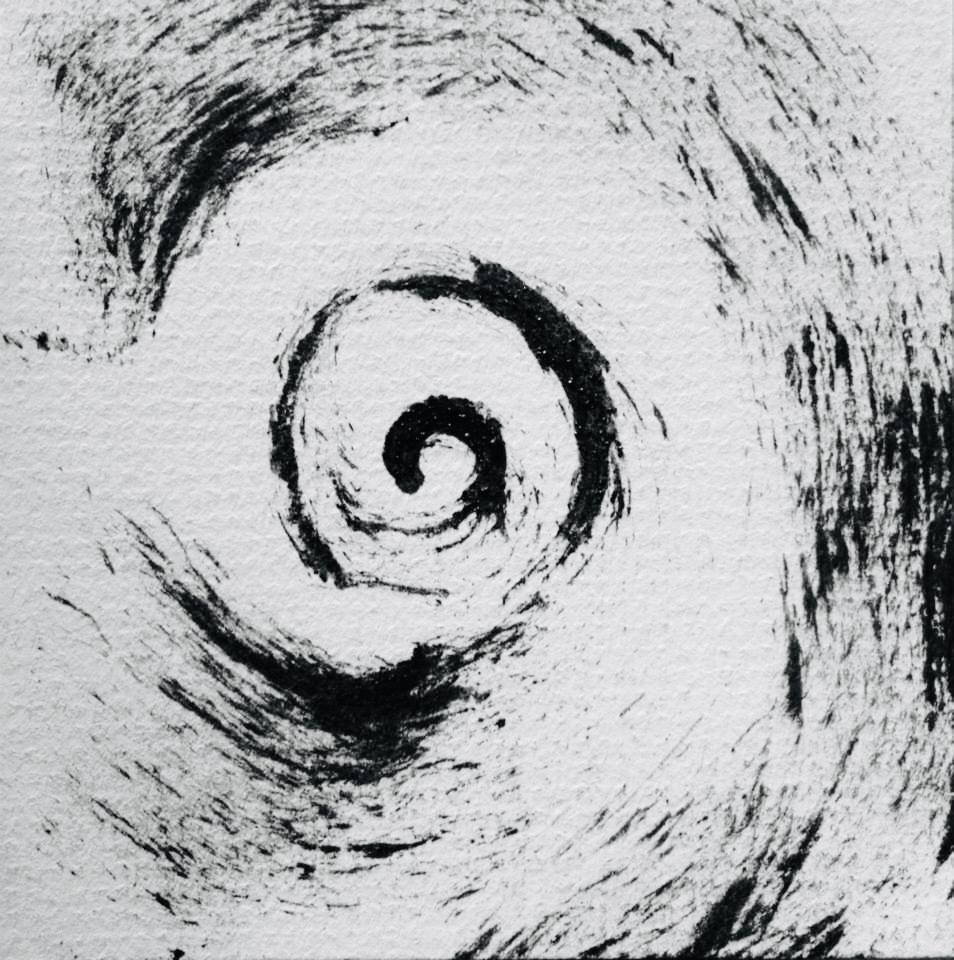

DRAWING ON A SINGLE BREATH

the way of the brush

A long time ago,

without any thinking,

I drew some pictures.

One picture =

one inhale,

one exhale,

one old mascara wand

on a 3” x 3” card

~30 seconds

*

*

आकाश

ākāśa

the sky breath

*

A participant in a recent calligraphy class I took online:

What about breathing?

Kazuaki Tanahashi, calligrapher and teacher:

Yes, breathing is a good idea.

*

The colours are always five, always in the same order: blue for space, white for air, red for fire, green for water, yellow for earth. Five little flags on a string, prayers flying in the wind. Lungta in Tibetan, the windhorse. Pre-Buddhist shamanistic objects now worked into Tibetan Buddhism, these are to be found everywhere in the Himalayas in various states of integration and disintegration—indoors and outdoors, under inscribed rocks, wound around trees and clothing lines, fluttering in the wind—the windhorse at the centre always bearing the wish-fulfilling jewel.

Dzogchen master Chögyal Namkhai Norbu says of the meaning of the lungta: “The word lungta (klung rta) is composed of two syllables: the first, lung, represents the element ‘space’ in the fivefold classification of the elements ‘earth, water, fire, air and space’ and signifies ‘universal foundation’ or ‘omnipervasiveness.’ […] The second syllable ta (horse) refers to the ‘excellent horse’ (rta mchog), and since in ancient times in Tibet the horse was the symbol of travelling with the greatest speed, in this case it seems to refer to the transmutation of every thing that depends on the five elements from negative to positive; from good to bad, from misfortune to good fortune, from baleful portents to auspicious signs, from poverty to prosperity, and it implies that this should ensue with the greatest speed.”

I find my first many years ago, a tattered white snarled in a thornbush.

*

༄༅། །རླུང་རྟའི་ཀ་འཛུག་བསྡུས་པ།

RAISING THE WINDHORSE

by Khachöpa, translated by Rigpa Translations

ཀྱེ། སྣོད་བཅུད་འབྱུང་བ་ལྔ་ཡི་ཀློང་། །

kyé, nöchü jungwa nga yi long

Kyé! The universe and its inhabitants, the expanse of the five elements,

ཡུམ་ཆེན་ལྔ་ཡི་ཐུགས་དབྱིངས་ནས། །

yumchen nga yi tuk ying né

Are the five mothers: from the space of their wisdom mind

འཁོར་འདས་རླུང་རྟའི་ལྷ་ཚོགས་རྣམས། །

khordé lungté lhatsok nam

All you deities of the windhorse, throughout saṃsāra and nirvāṇa,

འདིར་གཤེགས་རླུང་རྟའི་བ་དན་འབུལ། །

dir shek lungté baden bul

Come, approach! I offer the flag of the windhorse:

སྙན་གྲགས་རླུང་རྟ་རྒྱས་པ་དང་། །

nyendrak lungta gyepa dang

Increase our renown, rouse our windhorse, and

གཡུལ་ལས་རྒྱལ་བའི་ཕྲིན་ལས་མཛོད། །

yul lé gyalwé trinlé dzö

With your enlightened activity make us victorious over all!

And if you’re short on time and high on thin air, this is the warrior cry of the high mountain passes, the one that raises the lungta:

ཀི་ཀི བསྭོ་བསྭོ། ལྷ་རྒྱལ་ལོ།

ki ki so so lha gyal lo

May all the good forces be victorious!

*

WIND 12

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“காக்கை பறந்து செல்லுகிறது;

காற்றின் அலைகளின்மீது நீந்திக்கொண்டு போகிறது.

அலைகள்போலிருந்து, மேலே காக்கை நீந்திச்செல்வதற்கு

இடமாகும் பொருள் யாது?”

“The crow flies.

It swims on waves of air.

What is it that’s like the waves and what affords the flight of the crow?”

*

*

सूर्यभेद

sūryabheda

the breath that pierces the sun

*

THE FIRST VOWEL

Once upon a time, once our vocal and neural apparatuses had evolved to a tipping point, our pre-sapiens, pre-Homo ancestors did something that changed our world. They made sound that made meaning.

The earliest “language” was the ability to utter contrasting proto-vowel sounds. Which one might have been the first?

Was it u, uu, uuu—a coo, a huff, a roar? Was it o, oo, ooo—a moan, a call, a howl? Was it i, ii, iii—a chirp, a keen, a song? Was it e, ee, eee—a sob, a wail, a scream? Or was it a, aa, aaa—a breath, a sigh, a laugh?

In the Latin alphabet, such as we use for English, the vowel sounds are scattered among the consonants as if they’re all the same. And not all have names that match the sound they make. In abugidas or alphasyllabaries such as Devanāgarī used for Sanskrit, the vowel sounds come first. The consonants come later, in the order of where and how they are produced by the vocal apparatus. The consonants breathe through the vowels. They acknowledge their debt to the vowels—they pull into themselves अ a, and wear the signs of इ i, उ u, ए e, ओ o above or below, left or right. Each letter is called an अक्षर akṣara, imperishable. Its name is the exact sound it makes.

In Tamil, vowels are உயிர் uyir, “life” letters–the breath of life that goes into making a word. உயிர்ப்பு uyirppu, is both animation and reanimation, “rising alive.”

According to research, reading in an alphasyllabary creates activation in the left insula, fusiform gyrus, and inferior frontal gyrus (as with alphabetic scripts); the right superior parietal lobule (as with syllabic scripts); and bilateral activation in the middle frontal gyrus in line with the complex visual-spatial processing it demands. In other words, your brain lights up.

*

WIND 1

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“அதற்குக் கந்தன்: ‘அட போடா, வைதிக மனுஷன்!

உன் முன்னேகூட லஜ்ஜையா? என்னடி, வள்ளி, நமது

சல்லாபத்தை ஐயர் பார்த்ததிலே உனக்குக் கோபமா?’

என்றது.”

“Kandan said, ‘What’s the matter with you?

You’re such a Vedic type, such a puritan.

We’re not shy in your company, are we, Valli?

Are you upset that this Ayyar

saw us carrying on?’”

*

*

चन्द्रभेद

candrabheda

the breath that pierces the moon

*

“Now Garuḍa was reading hymn one hundred and twenty-one, in triṣṭubh meter. There were nine stanzas, each one ending with the same question: “Who (Ka) is the god to whom we should offer our sacrifice?” Estuary to a hidden ocean, that syllable (ka) would go on echoing within him as the essence of the Vedas. Garuḍa stopped and shut his eyes. He had never felt so uncertain, and so close to understanding,” says Roberto Calasso in Ka.

An unknown seed crystal touches the supersaturated solution of primal sound, and good salt crystallises. A last stop of air at the base of the soft palate, then the articulation. The first velar sound—from the Latin velum, awning, curtain, also where veil comes from—the first consonant, ka.

ka, cosmic waters and light; ka, space between earth and sky; ka, the question who?

The middle of the tongue touches the hard palate like a paintbrush to paper—the first palatal emerges soft, ca. The tip of the tongue curls up and back behind the alveolar ridge towards the hard palate, a quick strike-and-release—the first retroflex beats like a hand on a drum, ṭa. The tip of the tongue widens like a stream and abuts the dam of the upper teeth—the first dental spills, ta. The lips close and open—the first labial unstoppers like a marble in a golisoda bottle, pa.

From within to without, fully realised with the help of the vowels—the procession of the consonants.

In Tamil, consonants are மெய் mey, “body” letters. You want to talk, you better put body and soul together, let them breathe.

*

WIND 1

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“உடனே பாட்டு. நேர்த்தியான துக்கடாக்கள். ஒரு வரிக்கு

ஒரு வர்ணமெட்டு.

இரண்டே ‘சங்கதி’. பின்பு மற்றொரு பாட்டு.

கந்தன் பாடிமுடிந்தவுடன், வள்ளி. இது முடிந்தவுடன்,

அது. மாற்றி மாற்றிப் பாடி — கோலாஹலம்!”

“She began to sing. Short lilting songs.

A different tune for each line. And just two variations.

Then another song.

As soon as Kandan finished, Valli began her song.

One after another, they sang. A happy pandemonium.”

*

*

नाडीशोधन

nāḍīśodhana

the breath that clears the sun and the moon

*

“How did Joseph’s scent come to Jacob?

Huuuuu.

How did Jacob’s sight return?

Huuuu.

A little wind cleans the eyes.

Like this.

When Shams comes back from Tabriz,

he’ll put just his head around the edge

of the door to surprise us.

Like this.”

– Rumi, translated from the Farsi

by Coleman Barks in The Essential Rumi

*

I’m listening to Pär Boström’s dark ambient/dungeon synth project Aindulmedir as I work on this piece. I must admit it is the description that hooks me first: “music for bibliophiles and hermits.” That, and the first album art showing an old scholar deep in his books. The first track of The Lunar Lexicon is called Wind-Bitten. And that is what I am now. The wind has been taking bites out of me, and running me through. Slivers and bits. Huu.

The Sufi master Hazrat Inayat Khan speaks of the saut-e-sarmad, the abstract sound that “is the beginning and end of all sounds, be they from man, bird, beast, or thing.” Muhammed heard it in the cave of Ghar-e-Hira, he says, as did Moses upon Mount Sinai. अनाहतनाद anāhatanāda, the unstruck sound. “It sounds like (1) thunder, (2) the roaring of the sea, (3) the jingling of bells, (4) running water, (5) the buzzing of bees, (6) the twittering of sparrows, (7) the vīna, (8) the whistle, (9) the sound of śaṅkha—until it finally becomes (10) Hu, the most sacred of all sounds.”

The term sarmad refers to intoxication, but not of a material kind. There are other words—wajd, bhāva, ekstasis, mareacíon. In Spanish, mar is the sea. “So my voice becomes both a breath and a shout,” says Rainer Maria Rilke in The Book of Hours, “One prepares the way, the other surrounds my loneliness with angels.” Huu.

*

SAFAR/DUST IN THE WIND

Kārvān/Konya

I was thirty seven, and you,

perhaps three thousand.

Salâm. Sobh be kheyr. Esm e man

Jalāl ad-Dīn Muhammad Balkhī hast.

Holy darvish,

Shams-e-perende,

Kāmil-e-Tabrīzī—

I had not known then

that I had been looking

for you.

Tarīqā/Like this

I heard

you put a lock

worth a whole three

dīnārs on your door, left

with the key hanging

from your turban.

There was nothing

in your room, was there—

old rush mat, broken jug,

brick pillow. Exquisite

madman.

Ghazal/Damascus

I have been wandering

all over Dimašqu š-Šāmi,

Madīnat-al-Yāsmīn—where

are you?

Âtaš/When I die

Yā Allāh, had you

been looking

for me?

*

WIND 4

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“பாலைவனம்.

மணல், மணல், மணல், பல யோஜனை தூரம் ஒரே மட்ட

மாக நான்கு திசையிலும் மணல்.

[…]

வியாபாரக்கூட்டம் முழுதும்

மணலிலே அழிந்துபோகிறது.

வாயு கொடியோன். அவன் ருத்ரன். அவனுடைய ஓசை

அச்சந்தருவது.

அவனுடைய செயல்கள் கொடியன.

காற்றை வாழ்த்துகின்றோம்.”

“Desert,

Sand, sand, sand, for miles and miles the level sands in all four directions.

[…]

The entire caravan perishes in the sand.

The wind is cruel. He is Rudra, the Howler. His sounds terrify.

His acts are savage.

We praise him.”

*

*

स्वान

svāna

the panting breath

*

I subscribe to a newsletter that sends me various infographics about the state of the world. Today it has sent me one with a brown-paper background and smoky, stencilled text: MOST AIR-POLLUTED CITIES IN 2024. Byrnihat, Delhi, Mullanpur, Faridabad, Loni, New Delhi, Gurugram, Ganganagar, Greater Noida, Bhiwadi, Muzaffarnagar—11 out of the worst 20 are in India, in the no-man’s-land far beyond the WHO air quality guidelines. I live in a place that is a lot cleaner and greener, but I monitor my weather apps daily and check IQAir. I have acquired an air purifier.

Hazardous natural emissions, continued burning of fossil fuels, vehicle exhaust, industrial emissions, no proper laws or regulations. Smoke, ash, particulate matter, ground-level ozone, methane, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, oxides of nitrogen and sulphur, volatile organic compounds. Reduced lifespans, reduced healthspans. Increased incidence of anxiety, breathing trouble, eye trouble and headaches, respiratory infections, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diseases of the reproductive system, neurological and cognitive impairments. It even harms newborns and alters the brain structures of children and adolescents, increases the risks of dementia and Alzheimer’s. Unless you live in a forest or on a mountaintop, there’s no such thing as going out for a bit of fresh air.

We’ve been playing the same game since morning. My little nephew is teaching me UNO. We eat vanilla cake and discuss the relative merits of various dinosaurs. The game shows no signs of ending. He tries to coax me into the Show ’Em No Mercy version. He tells me he wants to go to Australia or New Zealand. Why? Clean air, he says. He’s the first kid I’ve come across who cites air as a reason for travel.

Rachel Carson wrote long ago about environmental pollution in The Silent Spring, and others continue to work and write. UN agencies now refer to climate change and air pollution as two sides of the same coin. “Killer air,” the BBC calls it. Amitav Ghosh’s words feel close in the perfectly named The Great Derangement: “By no means are the events of the era of global warming akin to the stuff of wonder tales; yet it is also true that in relation to what we think of as normal now, they are in many ways uncanny; and they have indeed opened a doorway into what we might call a ‘spirit world’—a universe animated by non-human voices.”

I once dreamt: Billions of years into the future, the sun has turned into a red giant and devoured Mercury and Venus. The surface of the earth has grown inhospitable. The air incinerates any life in an instant, and then takes what is left. A Morlocks-like human race still lives underground and children are in charge.

What is it that the poet said? “Hope is the thing with feathers…”

*

WIND 8

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“குளிர்ந்த காற்று வருகிறது.

நோயாளி உடம்பை மூடிக்கொள்ளுகிறான்.

பயனில்லை.

காற்றுக்கு அஞ்சி உலகத்திலே இன்பத்துடன் வாழமுடியாது.

பிராணன் காற்றாயின் அதற்கு அஞ்சி வாழ்வதுண்டோ?”

“Cold wind blows.

The sick man covers his body,

to no purpose.

You cannot fear the wind and live happily in the world.

Your breath is wind. How can you live scared of your breath?”

*

*

भस्त्रिका

bhastrikā

the breath that works like bellows

*

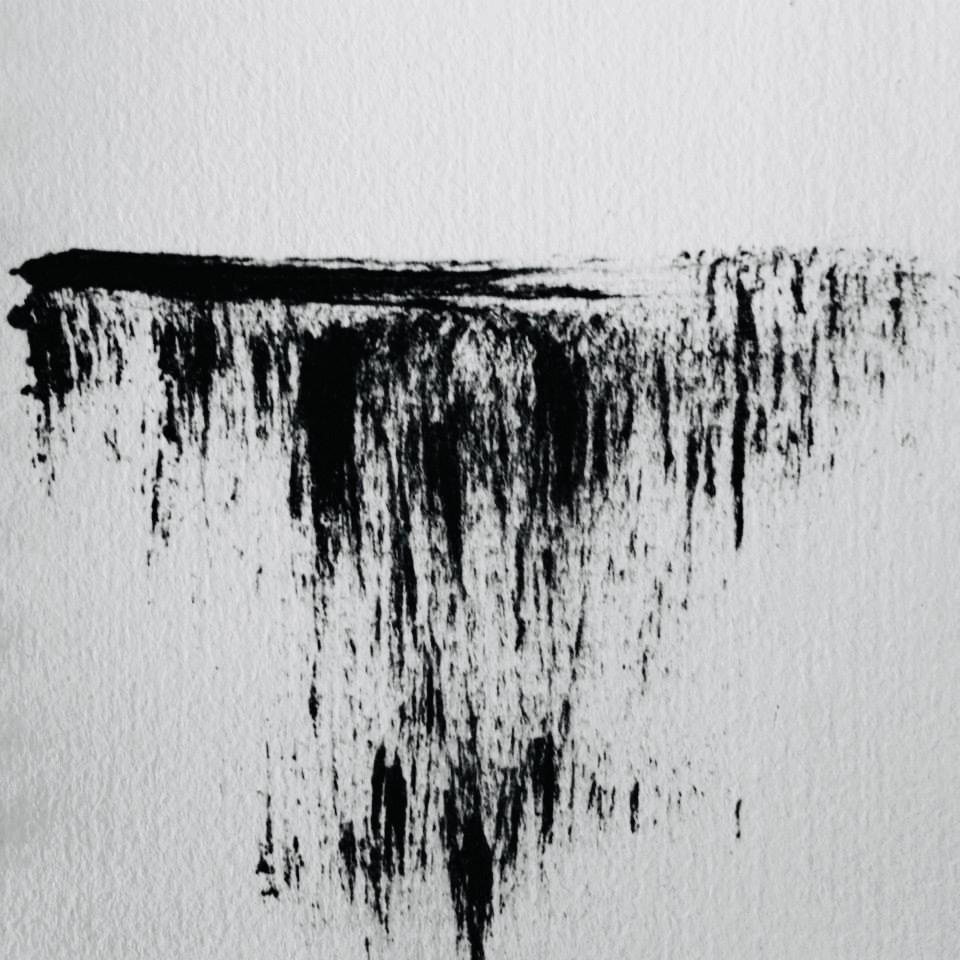

In 1805, Sir Francis Beaufort of the British Royal Navy looked around himself and used what he saw—the methods for setting sails on warships—to devise a scale for measuring wind speeds. Beaufort was not the first—a hundred years earlier, Daniel Defoe (whose Robinson Crusoe fame lay fifteen years in the future) had suggested a scale that used ordinary words to describe the winds.

Here is the current land version of the Beaufort Scale. It requires no measuring instruments, only observation of the effects of the winds in the world around us.

The scale started to sputter around 11 and 12, saying “widespread damage.” Where do you go from that? In 1946, the scale added five more levels—13 through 17.

Tropical storms are huge, spiralling wind systems with low-pressure centres that form over warm ocean waters. Over the South Pacific and the Indian Ocean, they are called cyclones; over the Northwest Pacific, typhoons; over the North Atlantic and the North Pacific central and east, hurricanes.

Scales shatter. Devastation knows no measure.

*

WIND 9

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“வலியிழந்தவற்றைத் தொல்லைப்படுத்தி வேடிக்கை

பார்ப்பதிலே நீ மஹா சமர்த்தன்.

நொய்ந்த வீடு, நொய்ந்த கதவு, நொய்ந்த கூரை,

நொய்ந்த மரம், நொய்ந்த உடல், நொய்ந்த உயிர்,

நொய்ந்த உள்ளம் — இவற்றைக் காற்றுத் தேவன் புடைத்து

நொறுக்கிவிடுவான்.”

“You’re very clever at poking fun at weaklings.

Delicate crumbling houses, crumbling doors, crumbling rafters, crumbling wood, crumbling bodies, crumbling lives, crumbling hearts

the wind god winnows and crushes them all.”

*

*

कपालभाती

kapālabhātī

the breath that shines the skull

*

Jean-Michel Jarre’s progressive electronica Oxygène is the cold, glassy, rarefied, almost-unbearable music of places very far, very high, very deep—the edges of the earth and beyond. Reinhold Messner, the great alpinist, listened to this during the first solo ascent of Everest without supplemental oxygen.

But my memory turns out to be wrong. When I reopen Messner’s The Crystal Horizon, what I read is that he plays this music during a lecture because he thinks the synthesizer tones are a good match. What he says elsewhere in the book has merged with this in my memory: “From the glacier tunnel through which it disappears comes a gurgling and rushing; at intervals the ice crackles. All these noises remind me of synthesized music. The glacier groans, snorts and squeaks. The tent flap stands open, to let in the fresh air.”

I’m thinking about thin air and mountains, and I need to know. Is my memory fickle about Annapurna, too? There are pictures, aren’t there? Here is my picture of Lake Tilicho at 16138 feet, and here is Maurice Herzog’s picture in his book, captioned The Great Ice Lake on the Tilicho Pass. Both taken around the same time of the year, in April, sixty-odd years apart.

But before that, before certainties. 13549 feet above sea level, a spot on the moonlit trail leading to the Annapurna base camp. A path so narrow I can only place one foot in front of the other, the colossal mountain rising to unseen heights to my right, the dark abyss yawning to my left. “Land is a poured thing and time a surface film lapping and fringeing at fastness, at a hundred hollow and receding blues. Breathe fast: we’re backing off the rim,” says Annie Dillard in Holy the Firm.

The Celts spoke of “thin places,” where the air is translucent, the skin is thin between worlds, and dreams come to eyes wide open. This place, so close I can see the lit lanterns in the camp across a bed of rounded rocks, almost hear the laughter of my friends, almost feel the warmth of the food and drink, yet so far, so cold, so perilous—this is such a place, a poet’s place.

It is on this mountain that Anatoli Boukreev perished in an avalanche, reverent revenant Boukreev that Jon Krakauer maligned in his bestselling Everest tragedy book, Boukreev who cared not for “conquests” like Herzog did, like others did. He said of mountains, “they are cathedrals, grand and pure, the houses of my religion.”

I’m merely a walker on mountains with my inadequate lungs and my old-injury knees full of glass shards, but even I see that the old Annapurna picture in the book is all ice, and mine is mostly water. It only took sixty years. I switch to Jarre’s luscious Waiting for Cousteau, a track that takes you deep underwater, to places you look at with wonder and places you do not want to go.

*

WIND 7

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“காற்றைப் பாடுகிறோம்.

அஃது அறிவிலே துணிவாக நிற்பது;

உள்ளத்திலே விருப்பு வெறுப்புக்களாவது.

உயிரிலே உயிர் தானாக நிற்பது.

வெளியுலகத்திலே அதன் செய்கையை நாம் அறிவோம்,

நாம் அறிவதில்லை.”

“We sing the wind.

It stands as courage in the act of knowing;

becomes love and hate in the heart,

is the breath in the breath of life.

In the world without, we know its actions, yet we know it not.”

*

*

शीतली

śītalī

the cooling breath

*

In a writing workshop the other day, I come across Ocean Vuong’s thoughtful notes on metaphor. “Moss intensifies up the tree,” he quotes Eduardo C Corral, “like applause.” I have been setting my bar too low. I should get myself a higher education in metaphor. I have read Borges and Eco and Calvino on the topic, but look, here are Bachelard and Lakoff and Sontag and others. And all of them thinking about metaphor a whole lot, asking of it a whole lot.

Gaston Bachelard speaks of airy things in Air and Dreams: “If we want really to know how delicate emotions develop, the first thing to do, in my opinion, is to determine the extent to which they make us lighter or heavier. Their positive or negative vertical differential is what best designates their effectiveness, their psychic destiny. This, then, will be my formulation of the first principle of ascensional imagination: of all metaphors, metaphors of height, elevation, depth, sinking, and the fall are the axiomatic metaphors par excellence. Nothing explains them, and they explain everything.”

He complains that “we understand so quickly that we forget to imagine,” and prescribes “the powerful reality of the mesomorphic state equidistant between mind and matter.” Does that help us with the Taoist butterfly dream that has intrigued us for a long, long time, an old metaphor?

“Once, Zhuang Zhou dreamed he was a butterfly, a butterfly flitting and fluttering about, happy with himself and doing as he pleased. He didn’t know that he was Zhuang Zhou.

Suddenly he woke up and there he was, solid and unmistakable Zhuang Zhou. But he didn’t know if he was Zhuang Zhou who had dreamt he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming that he was Zhuang Zhou.”

Rainer Maria Rilke says in The Sonnets to Orpheus, “True singing is a different breath, about/ nothing. A gust inside the god. A wind.”

*

WIND 10

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“மழை பெய்கிறது,

ஊர் முழுதும் ஈரமாகிவிட்டது.

தமிழ் மக்கள், எருமைகளைப்போல, எப்போதும்

ஈரத்திலேயே நிற்கிறார்கள், ஈரத்திலேயே

உட்கார்ந்திருக்கிறார்கள், ஈரத்திலேயே நடக்கிறார்கள்,

ஈரத்திலேயே படுக்கிறார்கள்; ஈரத்திலேயே சமையல்,

ஈரத்திலேயே உணவு.

[…]

குளிர்ந்த காற்றையா விஷமென்று நினைக்கிறாய்?

அது அமிழ்தம், நீ ஈரமில்லாத வீடுகளில் நல்ல

உடைகளுடன் குடியிருப்பாயானால்.

காற்று நன்று.”

“The rain pours.

The whole town is wet.

The Tamil people stand like water buffaloes, in wet forever, sit on the wet, walk on the wet, sleep on the wet, they cook on the wet, they eat on the wet.

[…]

You think the cold wind is poison?

It is ambrosia:

if you live in dry houses and wear proper clothes,

Wind is good.”

*

*

उज्जायी

ujjāyī

the breath of victory

*

वात॑स्य॒ नु म॑हि॒मानं॒ रथ॑स्य रु॒जन्ने॑ति स्त॒नय॑न्नस्य॒ घोष॑: ।

दि॒वि॒स्पृग्या॑त्यरु॒णानि॑ कृ॒ण्वन्नु॒तो ए॑ति पृथि॒व्या रे॒णुमस्य॑न् ॥

vātasya nu mahimānaṃ rathasya rujanneti stanayannasya ghoṣaḥ |

divispṛg yātyaruṇāni kṛṇvannuto eti pṛthivyā reṇumasyan ||

Now (I shall proclaim) the greatness of Wind and of his

chariot: shattering as he goes: thundering is his sound.

Touching heaven as he drives, turning things red, and tossing up dust

from the earth as he goes.

सं प्रेर॑ते॒ अनु॒ वात॑स्य वि॒ष्ठा ऐनं॑ गच्छन्ति॒ सम॑नं॒ न योषा॑: ।

ताभि॑: स॒युक्स॒रथं॑ दे॒व ई॑यते॒ऽस्य विश्व॑स्य॒ भुव॑नस्य॒ राजा॑ ॥

sam prerate anu vātasya viṣṭhā ainaṃ gacchanti samanaṃ na yoṣāḥ |

tābhiḥ sayuksarathaṃ deva īyate’sya viśvasya bhuvanasya rājā ||

The dispersed eddies of the Wind press forward together following (him).

They go to him, like girls to a festive gathering.

Yoked together with them on the same chariot, the god speeds on as

king of this whole world.

– Hymn to Vāta/ Vāyu by Anila Vātāyana,

ऋग्वेद Ṛgveda 10.168,

translated from the Sanskrit by Jamison & Brereton

*

Noting the Apollonian/Dionysian contrast between Vedic Agni and Soma (though I’m not sure how long this contrast will hold), Ramanujan says of soma, the substance: “psychedelic, mind-blowing… part of the ecstatic religion of the time, not easily contained by social arrangements.” He quotes the Frits Staal translation of the Ṛgveda 10.136, Hymn of the Long-Haired Ones (the Jamison and Brereton translation is more accurate, but we need wilder vibes):

“Long-hair holds fire, holds the drug, holds heaven and earth.

Long-hair opens everything under the sun. Long-hair declares it light.

These sages swathed in wind, put dirty red tatters on,

When gods get in them, they ride with the rush of the wind.

‘Crazy with wisdom, we have lifted ourselves to the wind.

Our bodies are all you mortals can see.’”

*

This intoxicating soma—who gets the first drink in the morning pressing? Vāyu, the Wind. But why is this privilege his alone?

Roberto Calasso in Ardor: “There is always something prior to the gods. If it is not Prajāpati, from which they originated, it is Vṛtra, an amorphous mass, mountain, snake on the mountain, goatskin, a repository for the intoxicating substance soma.”

Indra has slain the great Vṛtra with his thunderbolt, but the work is not done yet.

“The gods rushed off. They knew that Vṛtra’s body was swollen with soma, since Vṛtra was born from soma. Each wanted to plunder the corpse, to take the largest portion of it. They realized that the soma stank: ‘Its pungent stench wafted toward them: it was not fit for offering nor was it fit for being drunk.’ So once again they asked for Vāyu’s help: ‘Vāyu, blow over him, make him palatable for us.’”

Nectar, nectar within decomposition, within poison. And air. Ambrosia.

“Indra said he wished, through soma, to have language—indeed, the articulated word. From that time on, through Prajāpati’s decision, of all the languages throughout the world, only a quarter are articulated, and therefore intelligible. All the rest are indecipherable, from the warbling of birds to the noise of insects.”

There was more to the word than Indra thought. There was more in the air.

“The unmanifest is much greater than the manifest. The invisible than the visible. The same also with language. We must all know that when we speak, “three parts [of language], kept in concealment, are motionless; the fourth part is what people use.”

*

अ॒न्तरि॑क्षे प॒थिभि॒रीय॑मानो॒ न नि वि॑शते कत॒मच्च॒नाह॑: ।

अ॒पां सखा॑ प्रथम॒जा ऋ॒तावा॒ क्व॑ स्विज्जा॒तः कुत॒ आ ब॑भूव ॥

antarikṣe pathibhirīyamāno na ni viśate katamaccanāhaḥ |

apāṃ sakhā prathamajā ṛtāvā kva svijjātaḥ kuta ā babhūva ||

Speeding along the paths in the midspace, he does not settle down on any

single day.

Comrade of the waters, the first-born abiding by truth—where was he

born? from where has he arisen?

आत्मा देवानां भुवनस्य गर्भो यथावशं चरति देव एषः ।

घोषा इदस्य शृण्विरे न रूपं तस्मै वाताय हविषा विधेम ॥

ātmā devānām bhuvanasya garbho yathāvaśaṃ carati deva eṣaḥ |

ghoṣā id asya śṛṇvire na rūpaṃ tasmai vātāya haviṣā vidhema ||

The breath of the gods, the embryo of the world, this god wanders as he

wishes.

Only his sounds are heard, not his form. To him, to the Wind, we would

do honor with our oblation.

– Hymn to Vāta/ Vāyu by Anila Vātāyana,

ऋग्वेद Ṛgveda 10.168,

translated from the Sanskrit by Jamison & Brereton

*

WIND 1

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“காற்றுத் தேவன் தோன்றினான்.

அவனுடல் விம்மி விசாலமாக இருக்குமென்று

நினைத்திருந்தேன்.

வயிர ஊசிபோல் ஒளிவடிவமாக இருந்தது.”

“The wind god.

I had imagined he would be big in body.

He was a diamond needle, a body of light.”

*

*

मूर्छा

mūrchā

the swooning breath

*

“My place is placeless, a trace

of the traceless. Neither body or soul.

I belong to the beloved, have seen the two

worlds as one and that one call to and know,

first, last, outer, inner, only that

breath breathing human being.”

– Rumi, translated from the Farsi

by Coleman Barks in The Essential Rumi

*

UNWRITTEN POSTCARD FROM THE DRAGON CAVE

Dear T: If you were here, you would find yourself in the blue hour. This cave—floor worn smooth from the thousands of feet that have passed before, walls slick from the wet and fragrant from the incense, ceiling so low it bows our heads before the flickering butter lamps—you would hold my hand and step into this cave with me. We would be in the subterranean heart of this mountain that we looked upon before. Who would have thought that the lush pines, firs, and cedars harboured such a place within? If you were here, you would find yourself inbetween. ps: I would take you to Milarepa Cave, but we would need to learn levitation first :-)

*

THE VERY LEARNED PANDIT WHO NAMED HIS DAUGHTERS MĀYĀ AND LĪLĀ

Once upon a time in Varanasi, there was a very learned pandit. The very learned pandit’s young wife had given birth to twin girls and then shed her mortal coil. The very learned pandit named his daughters Māyā and Līlā—divine illusion and divine play—and handed them over to his retinue of ayahs, cooks, and servants to raise.

The girls grew up brilliant and beautiful. Whenever he had guests over, which was often, the very learned pandit would call his brilliant and beautiful daughters to the ornate living room, prompt them to show off their scholarly and artistic abilities, and then proceed to smile and nod knowingly about how clever their names were. The guests would also smile and nod back knowingly, affirming that the names were clever indeed. The very learned pandit would then rub his very large belly in satisfaction and call for more hot spiced chai and sweets.

Early one evening, the very learned pandit came back home with some very important guests and called out—Māyā! Līlā!—while smiling and nodding knowingly. No one appeared. The very learned pandit knocked on the girls’ door. The door swung inward. A large bay window lay open to the deep blue sky. White muslin curtains were blowing in the wind.

*

WIND 5

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“வீமனும் அனுமானும் காற்றின் மக்கள் என்று

புராணங்கள் கூறும்.

உயிருடையனவெல்லாம் காற்றின் மக்களே என்பது வேதம்.”

”The old myths say Bhima and Hanuman are the sons of the wind.

The Veda says, all breathing things are children of the wind.”

*

*

भ्रामरी

bhrāmarī

the breath of the honeybee hum

*

“The greatest illusion of this world is the illusion of separation. Things you think are separate and different are actually one and the same.”

– Guru Pathik teaching Aang the principle of inner light,

Avatar: The Last Airbender, S02E19 The Guru

*

I read about her on the back of a DVD cover. I’m in a shop in the old Fortune Centre, where I go every now and then to rummage for herbs and dried flowers and assorted shiny things. In minutes, I have called and essentially asked to meet please please please because huge imposition.

When I meet her and her longtime friend and associate for teh-c at some Singapore kopitiam, late morning sun is dappling through foliage and picking shiny spots out on the cracked formica tabletop. If it is an imposition, she doesn’t show it. They both welcome me with big smiles, pressing tea upon me, this perfect stranger who has burst upon them. Something about her gets a hold of me and I cannot get any words out. I find that I’m hugging her and that my eyes are streaming.

My friend Teresa Hsu was born in Guangdong province in China in 1898. Canton. When I meet her for the first time, she is 112 years old (113, she corrects me, because we start counting at conception). I call her Angel and often take her and Brother Sharana homecooked soups and vegetables. Not that they need any help—they are more active than I am, kinder and more joyful than anyone I have met. They thrust gifts upon me—fruit, books, a blender once. We talk for hours and hours and go for ice cream.

I visit her in hospital. She looks so small surrounded by tubes and equipment. Brother tries to feed her baby food from a tiny jar with a tiny spoon. But she has decided it is time, and he brings her home. I visit her at home, this place with wall-to-wall books, even books dedicated to this woman who ate grass during a famine, who taught herself to read and write and devised a new writing system, who saw two great wars and served as a nurse in the second, who lost her single love, a pilot, in a crash, who always worked for the powerless, who opened an old-age home for those decades younger than herself, who finished her memoir just the other day. I sit on her bed.

I’m no longer sure she knows me. Her eyelids flutter. With what strength I do not know, but she sits up for a moment. I rush to hold her. She kisses me on my lips—a kiss light as a baby’s breath, a mere brush of a feather, air. I’m the child she never had. I’m the pilot falling through burning air. I’m me. She falls back. And in three days, she is gone.

*

THIS IS HOW THE DAY WILL COME

this is how the day will come

your breath will fall

quiet as an amber leaf

your heart will be still

your mind extinguished

riven from end to end

I will fall upward

this is how the night will come

*

لے سانس بھی آہستہ کہ نازک ہے بہت کام

آفاق کی اس کارگہ شیشہ گری کا

le sāñs bhī āhista ki nāzuk hai bahut kām

āfāq kī is kārgah-e-shīshagarī kā

Draw your breath gently, its workings are brittle and

delicate.

These four quarters of the world: a glassmaker’s

workshop.

– Mir Taqi Mir, translated from the Urdu

by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi in Ghazals

*

WIND 8

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“காற்று வருகின்றான்.

அவன்வரும் வழியை நன்றாகத் துடைத்து நல்ல நீர்

தெளித்து வைத்திடுவோம்.

அவன்வரும் வழியிலே சோலைகளும், பூந்தோட்டங்களும்

செய்து வைப்போம்.

[…]

அவன் நல்ல மருந்தாக வருக.”

“Here comes the wind.

Let us wipe clean his pathways, let us sprinkle water on them.

Let us make groves and flowering arbours in his pathways.

[…]

May he come as a healer.”

*

*

प्रणव

praṇava

the breath of the cosmos

*

“This is the truth. They stood on the stones in the lightly falling snow and listened to the silvery, trembling sound of thousands of keys being shaken, unlocking the air, once upon a time.”

– Ursula K Le Guin, Unlocking the Air

*

“Whirling sky, watch how the elements whirl.

Water is drunk, air is drunk, earth is drunk, fire is drunk.

Don’t even ask about the unseen.

Spirit is drunk, intellect is drunk, imagination is drunk.

And the mysteries of eternity—

they’re the drunkest of all.”

– Rumi, translated from the Farsi

by Haleh Liza Gafori in Gold

*

WIND 5

Excerpt by Subramania Bharati,

translated from the Tamil by AK Ramanujan

“சிற்றுயிர் பேருயிரோடு சேர்கிறது.

மரணமில்லை.”

“The little breath joins the great breath.

There is no death.”

*

Kanya Kanchana is a poet and philologist from India.

CREDITS

– Image: Pink cherry blossoms against a blue sky. Cambridge, England.

– Instructions for a Novice, first published in Global Conversations, Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities, University of Cambridge; Safar/Dust in the Wind, first published in The Bangalore Review; This is how the day will come, unpublished; The Very Learned Pandit Who Named His Daughters Māyā and Līlā, unpublished

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: