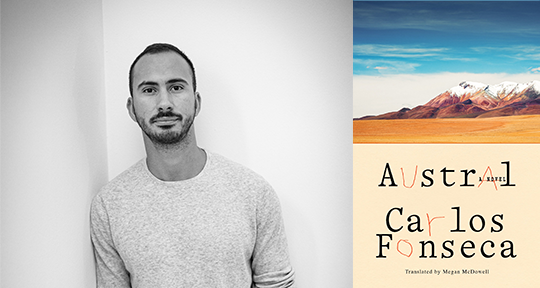

Austral by Carlos Fonseca, translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023

“What is the social impact of translation?” is a question that often buzzes in my ear like a hungry mosquito, especially when I read translated books, and even more commonly when I try to teach colloquial expressions in Spanish to my non-Hispanic friends—more precisely, Spanish from Mexico City, my hometown. Immediately, attempts at clear definitions become convoluted, uncertain, ambiguous—in a word, atropellados (literally “ran over,” an adjective that refers to stumbling over words). I sound more or less like this:

“Take ‘chido/chida/chide’ [CHEE-duh/-da/-de] (adj.). It can technically mean ‘cool,’ but also ‘good,’ ‘agreeable,’ or ‘comfortable’ (for things and places and preceded by the auxiliary verb ‘estar’); it also means ‘nice-kind-laidback-easygoing-friendly’ (for someone who meets all and every one of these attributes and with the verb ‘ser’); or ‘ok, no problem,’ and ‘thank you’ (in informal social interactions with a close friend but not necessarily an intimate one and, crucially, with an upbeat intonation)…but if you want to make things easier for you, just remember that in any colloquial situation where you would say ‘cool’ in English or the closest equivalent in your mother tongue, you can say ‘chido.’ Don’t forget to adjust the last letter for the grammatical gender of the noun, or the preferred gender of the person you are referring to. Recently, non-binary gender is expressed with an ‘e,’ but some people prefer ‘ex,’ or the feminine (a), or do not have any strong preference. When in doubt, ask.”

Similarly involved and protracted explanations often result in simpering faces and jocose efforts by my bravest friends to try out the words I share. More common, and more fun, is when friends also share their favorite colloquial untranslatables in their mother tongues, eliciting everyone’s excited perplexity and marvel at the abundance of meaning and the frustrating difficulties of carrying that meaning across languages and cultures. When we try to explain these terms, it is as though their translation abruptly hits the brakes on our language, pushing us into linguistic confusion with the inertia from the sudden interruption. In other words, translation begets disorder, upsetting the comfortable and normally thoughtless flow of everyday language. This sensation—which emerged in me after my recurrent attempts at translating colloquialisms—appears more subtly and robustly in the 2023 novel Austral by Carlos Fonseca and its translation by Megan McDowell. Disorder, Austral suggests, lies at the heart of translation’s social potential, as it makes translation (its exercise and its experience) essential for radical change.

The first paragraphs of the book intertwine translation and disorder. Through an extended and meandering description of an image on a postcard, the first words of Austral set up the central theme of the book—memory—and its main narrative plot: the trip of the main character, Julio Gamboa, from the United States to South America to learn more about an unpublished manuscript of his dead friend Aliza Abravanel. This opening description performs what Roman Jakobson calls intersemiotic translation, the relocation of meaning from one symbolic regime to another, in the case of Austral from the visual to the linguistic. Shortly after beginning the novel, we read the following transfixing lines:

He has never been in a desert before, but he has imagined them often.

That’s why every time he looks at the postcard he now holds in his hands, his first instinct is to see in it a portrait of the arid plain. Little does it matter that the photograph is in black and white. He imagines the tons of sand, the atmosphere of tedium, the feeling of emptiness. It seems there is no one in the image, just a dozen lines meticulously arranged that his eyes transform into the empty streets of an old mining town. He sees the white drifts at the edges of the postcard and tells himself they are clouds. But then he starts to doubt.

On a closer look the white splotches lose their lightness and start to resemble heaps of salt. Just like that, the desert becomes a giant salt flat. The lines on the plain mark the paths the cars full of saltpeter would travel along in this abandoned plant that reminds him, in a last twist of fancy, of the wrinkled lunar surface, with its craters and valleys, its archaic geometries. Only in that moment, when his imagination is exhausted, does he remind himself of what he knows: this is just a photograph of a dirty window, and where he’d thought he’d seen a desert landscape, a salt fat, or the moon, there is only dust.

Julio’s perception is tarnished by imagination, unfamiliarity with the place in the picture, and the emotions stirred by memories associated to the image—a youthful adventure through a war-shaken Central America with Aliza, who commissioned him to edit her last manuscript, and whose acquaintances sent him the postcard that begins the story. As we can read, the translation of the image to the narrated text is neither orderly nor unambiguous. Rather, the stumbling and shifting perceptions of what the image shows forego a direct representation or an exact description, pulling us readers into a profound uncertainty that mirrors Julio’s experience of the postcard. In other words, the inter-semiotic translation of the fictional image ambushes our perception with the opacity of Julio’s subjective and meandering repertoire of possible senses for the image. Translation here equals disorder in the realm of perceptual certainty.

But, this disorder goes beyond the novel’s language. Indeed, closely connected to it is the disorder introduced into Julio’s life by the postcard and the series of events that unfold after its arrival. Suddenly, Julio’s monotonous life as a professor in an American university becomes haunted by a past that he struggles to remember, but is also reignited by the posthumous intimate request of his friend, whom he had not talked to in years. This association between his forgotten past, the disorder it brings into his life, and translation is cemented when he talks to Olivia Walesi, Aliza’s friend and sender of the postcard. Olivia, recounting to him the last days of Aliza’s life, “seemed to be translating into Spanish thoughts that had come to her in English. It was in those moments that the story’s voice finally managed to blend with its subject, and he felt that the person speaking was not Olivia Walesi but rather his friend Aliza Abravanel.” With Olivia, the disorder of translation goes so far as to destabilize naturalized configurations of identity and subjectivity. Through uncertain perception, upset quotidian monotony, and confused personal identity, disorder plagues the opening pages of the book, always in tight connection to translation.

Such association appears beyond the novel’s initial paragraphs. Far from a passing motif, the portrayal of translation as disorder shows up in other key parts of Austral, and is in fact central to one of the main subplots. The story of the anthropologist Karl-Heinz von Mühlfeld and his attempt to save the Nataibo indigenous language from disappearance—recounted by Aliza in one of her manuscripts—stirringly embodies the complexities of regarding translation as disorder. In the story retold by Aliza, von Mühlfeld travels to New Germany in Paraguay to find evidence for his developing theory of linguistic hybridity. There, he becomes acquainted with Juvenal Suárez, the last speaker of the Nataibo language, whose voice he records with the aim of creating a dictionary. At this point in the story, the disorder of translation appears as the refusal to accept cultural disappearance, as both von Mühlfeld’s and Suárez’s affront to the disaster and tragic destiny of the loss of a language. Yet, the association of translation and disorder eventually takes on a more troubling shape. Years after that initial interaction with the anthropologist, Suárez falls into alcoholism and self-isolation, refusing to speak Spanish and opting instead for a ceaseless monologue in his native Nataibo that only he can comprehend, thus condemning his language and culture to disappearance.

Here, translation, in its absence, brings about disorder as the rejection of anthropology’s encyclopedic desire to preserve a language detached from the people who speak and live it. The disorder that ensues from Suárez’s refusal to translate his native language works as a tragic form of resistance against Western knowledge and modernity, systems that are also complicit with the disappearance of the Nataibo people. After reading about this episode in Aliza’s diary, Julio himself interprets Suárez’s refusal of translation as resistance: “[Julio] told himself that precisely here was where Juvenal Suárez’s courage lay: in his refusal to become a mere tourist object.” Presenting disorder as Indigenous resistance, this subplot of the novel hints at the radical potential of disorder’s association to translation—here as something to be refused—but it does so without falling into easy optimisms. After all, the novel suggests, though disorder can be strategically weaponized as resistance against Western colonialism and imperialism, the price to pay might be disastrously high.

The unconventional coupling of translation as disorder is not only present in the above anecdotes, but established throughout as a main theme of the text. What is the impact, beyond the book’s diegesis, of such a way of conceiving translation? What is this disorder subverting, challenging, or complicating? We might approach an answer by focusing on the contexts in which Austral circulates, that is, the global channels of contemporary literature in translation. In particular, the novel joins forces with other voices that, through literature, challenge dominant cultural and media industries. My thinking on this matter is informed by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s political analysis of contemporary cultural globalization. In their book Empire, these philosophers highlight the key role that dominant cultural conglomerates play in sustaining global political, racial, and economic hierarchies:

Communications industries have assumed such a central position. They not only organize production on a new scale and impose a new structure adequate to global space, but also make its justification immanent. Power, as it produces, organizes; as it organizes, it speaks and expresses itself as authority. Language, as it communicates, produces commodities but moreover creates subjectivities, puts them in relation, and orders them. (33)

Against this imposition of order and subjectivity, complicit with global oppressive systems, translation and the disorder that it begets become radical counter-attacks. Literature in translation brings into global consciousness the possibility of other worlds, other subjectivities, and other ways of perceiving life, interrupting the circulation of prevailing constructions of reality. Therein lies the power—or at least one of the powers—of translation’s disorder, in its strong ability to upset the world order that, according to Hardt and Negri, transnational media complexes present as the only possible form of viewing and feeling life. Through translation, as Austral suggests and demonstrates, histories of war, violence, and tragedy, but also ways of conceiving friendship, survival, and memory, reclaim space as concerns for all of us, regardless of but also in close connection with nationality, language, and personal identity. This refusal of historical oblivion and invisibility is one of the most disorderly gestures embodied by the novel, and thereby one of its most radical ones.

However, such a sweeping potential for translation is not limited to the literary. Rather, it surfaces in everyday instances—such as my attempts at explaining colloquialisms from Mexico City’s Spanish to my non-Hispanic friends. The rupture of language and the overflow of meaning during translating acts stress language’s complexity and unsettledness. When we translate, we slow down our linguistic flow, denaturalizing and reconfiguring it for the understanding of non-speakers. In that pause and break with language’s usual inertia lives the possibility for unspoken utterances and unimagined realities. In its disordering of language, translation allows us to think of new and better worlds. After such pause, though, it falls upon the creativity of communities and individuals to actualize the radical possibilities of their imaginations.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: