This month, we are taking a look at works from world literature that unveil the universal intersections at the centre of society: an empathetic interrogation into the cross-section of contemporary life in a superstore by the inimitable Annie Ernaux; a brilliantly curated selection of humanist stories from the Swahili; and a subtle, delicate look into the nature of happiness as written into dialogue by lauded Polish author, Marek Bieńczyk. Read on to find out more!

Look at the Lights, My Love by Annie Ernaux, translated from the French by Alison L. Strayer, Yale University Press, 2023

Review by Laurel Taylor, Assistant Editor

Even at its best, ethnography is an ethically tricky subject; at its worst, it can dehumanize, tokenize, and Other the people who fall under its burning eye—an eye so often situated in wealth, power, whiteness, and patriarchy. Annie Ernaux is all too aware of the treacherous ethnographic ground she walks in Regarde les lumières mon amour, originally published in 2014 and translated now into an incisive and unadorned English by Alison L. Strayer as Look at the Lights, My Love. In this brief but gripping nonfiction entry, Ernaux records her various visits to the French big-box store Auchan from November 2012 to October 2013, a period which happens to coincide with the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse in the Savar sub-district of Dhaka, Bangladesh.

For all its drab ubiquity and late-capitalist imbrication, Ernaux treats the site of the superstore not only as a place perpetuating a unilateral and devastating economics (in the broadest sense of the word), but also one which engages humanity in complex ways—affectively, socially, temporally.

. . . when you think of it, there is no other space, public or private, where so many individuals so different in terms of age, income, education, geographic and ethnic background, and personal style, move about and rub shoulders with each other. No enclosed space where people are brought into greater contact with their fellow humans, dozens of times a year, and where each has a chance to catch a glimpse of others’ ways of living and being. Politicians, journalists, “experts,” all those who have never set foot in a superstore, do not know the social reality of France today.

Indeed, it feels almost taboo in the often inward-facing world of Parisian literature to engage with something so blasé as a big-box store. At one point, Ernaux even says in an aside, “I don’t see Alain Robbe-Grillet, Nathalie Sarraute, or Françoise Sagan doing their shopping in a superstore; Georges Perec yes, but I may be wrong about that.” For me, this is what makes Ernaux’s earnest attempt at engagement all the more relevant (and close-to-home, as I grew up in a squarely middle-class family that did most of its shopping at a big-box store). In addition to the unconventional topic, this particular book also feels difficult to classify. Neither journalism nor something so structured as a dialectic, Look at the Lights, My Love is something more akin to mindfulness. It is an attempt to deliberately undo the asynchronous pace of the superstore—a place where flash sales, labyrinthine design, ever-changing displays, and the press of daily chores all collude to entrap and entangle us in the past, present, and future all at once. Ernaux’s thick descriptions, in trying to circumvent these snares, work to better provide us with “[a] free statement of observations and sensations, aimed at capturing something of the life of the place.”

The denizens of Auchan vary in every way imaginable, and Ernaux finds herself coursing and recoursing the trajectories of their lives in this space of contact. In January, “[in] the deserted automotive accessories department, a small black child played with a large cardboard box in the aisle. I wanted to photograph him. Then I wondered if there was not something of the colonial picturesque in my desire.” In April, “there is [no one] at the self-checkout, where a lost-looking girl is growing increasingly upset, not knowing where to put the items she takes from her basket, and driven to panic by the eyes that watch her every movement while the robot voice intones, over and over, ‘Place your items on the scale,’ as if it were dealing with a halfwit.” Shortly thereafter, “[i]t is the May school holiday period and the crowd is mostly women with shopping carts and children. I imagine the mighty line that all these mothers would form, scattered through the store with their carts and children, moored to subsistence and child-rearing. A pre-historic vision.” The web of human contact within Auchan allows Ernaux to dissect the intersectionality of French society, following each strand down paths that confront poverty, racism, sexism, and capitalist exploitation, as well as the grinding oatmeal affect of mass consumerism.

To call a translation plain is often considered an insult—it insinuates the translator has somehow flattened what must have been sparkling in the original, but Ernaux’s prose has, especially since her 2022 Nobel win, been described with words like “austere” and “analytical” or “direct” and “declarative.” In 1983’s La place, she even self-described her work as l’écriture plate—“flat writing.” This makes Strayer’s translation of this brief work all the more effective precisely because of how carefully she controls her own vocabulary and syntax. Much of the text is kept in the Germanic register rather than the Latinate, and even sentences that sprawl—as with the portrait of the panicked young girl above—still paint a clear and linear flow in the English. This feels even more apropos in the glare of oppressive big-box fluorescents, which deaden the language intended to attract and warn us in turns.

WE WISH TO INFORM OUR VALUED CUSTOMERS THAT FITTING ROOMS MUST ONLY BE USED FOR TRYING ON CLOTHING (LIMIT 3 PER PERSON).

In plain speak (always translate superstore language), it is forbidden to sleep, eat, make love in the fitting rooms.

Ernaux is translating the message of our consumerism, the sparkling ads which belie the slave labor and sweatshop conditions that support behemoths like Auchan. Two disasters—the deadly fire at Tazreen Fashions in Bangladesh in November and the collapse of Rana Plaza in late April—both struck factories which had supplied garments to Auchan and many other mega corporations, and those tragedies haunt this work. The entries Ernaux dedicates to them, despite being some of the shortest in the book, are the ones that ring most damningly, illustrating the ways in which our supply chains continue to perpetrate exploitative labor both at home and abroad. At the same time, however, Ernaux does not plaster the whole affair with a scarlet letter. The bitter mixes with the sweet, and our own innate fascination with the novel, the bright, and the alluring complicates this space of contact.

Afternoon. A dense crowd as soon as one enters the shopping center. A very loud bussing noise through which the music can barely be heard. On the inclined moving walkway, under the glass roof, we ascend toward the lights and garlands hanging down like necklaces of precious stones. The woman in front of me with a little girl in a stroller looks up and smiles. She leans down toward the child. “Look at the lights, my love!”

Childlike wonder, warmth, buzzing discomfort, the crush of people, commands to buy, claims of extraordinarily generous deals. Ernaux’s ambivalence for the supercenter is the ambivalence so many of us feel as we subsist in this world, contemplating the systems that intersect at the crossroads of our bodies, most often converging in the pocket where our wallets are kept.

No Edges: Swahili Stories, by various authors, translated from the Swahili by various translators, Two Lines Press, 2023

Review by Sofija Popovska, Editor at Large for North Macedonia

Have we forgotten what it means to be human?

No Edges is a mosaic of mirrors, magnifying gentleness and cruelty, madness and reason in dizzying visions of the present and future. What struck me immediately upon finishing this pungent and thrilling little volume was the way it centered empathy and community—a far cry and a refreshing detour from the majority of current popular fiction, which tends towards fraught depictions of insular existence and the attendant ennui. Each of the eight featured stories (and excerpts) reveals the ways in which we connect: some explore relationships between lovers, neighbors, and families; others expand the scope and consider governments, or even the progression of human society from past to present. If this sounds like I’m describing a ‘slice of life’ type narrative, filled to the brim with moderately eventful dialogue, then I’ve deceived you—No Edges also happens to be one of the wildest rides I’ve ever taken as a reader, and you would likely agree. In this quilt of fantasy and reality, witches, otherworldly beasts, futuristic executions, and landscapes of the afterlife appear alongside depictions of after-school hours, workaday vignettes, and funerals gone awry.

By plunging us into the unfamiliar, No Edges brings us closer to the human. In an excerpt from Walenisi, a novel by Katama G. C Mkangi, an innocent man is sentenced to execution by spaceship; to lend the viciousness a veneer of bureaucratic propriety, he is allowed five minutes to read the instructions to the ship’s controls. “We have emerged from barbarism,” proclaims his executioner, “these rights give the condemned a chance . . .” Meanwhile, the steering wheel is rendered inoperable by being fixed in place, and the crowd below is saturated with righteous judgment. “That’s the best remedy for talking too much,” proclaims an onlooker who, like everyone else, is unaware of whether the man is really guilty. Thus, while set in the future, the narrative reveals a familiar scene: systemic corruption and a lack of empathy at large. In this “universe with no edges,” humanity insists on preserving its limitations by leaning into selfishness and division.

Lusajo Mwaikenda Israel’s A Neighbor’s Pot offers a phantasmagoric, albeit less grave, spin on this theme. A young girl is sent to a monstrous parallel dimension, tortured, and almost devoured at a sorcerers’ feast—all because her mother had broken a neighbor’s earthenware pot. The story certainly plays up the discrepancy between the crime and the punishment, but its underlying realism is carefully rendered: the value of healthy communication is emphasized when the narrator notes that the witch behind the heinous revenge plot hadn’t ever taken up the offense with the girl’s mother, saying instead “Just drop it, neighbor, what’s a pot, I have another.” Despite seeming to wave off the incident, the witch then went on to nurse “a grudge, and nourished it with her hypocritical laughter.” This choice to hold on to her resentment instead of giving the other side an opportunity to reconcile is unfortunate, but not unsurprising. Empathy is at the heart of communication, and people so often opt to insulate their true feelings based on a sense of disdain for others—something equally bad for the individual as it is for the collective. “Like the Swahili say,” explains the narrator, “the thing that’s eating you is inside your own clothes.”

Attitudes by Fadhy Mtanga and the excerpt from Selfishness by Lilian Mbaga reiterate the importance of our communities, both temporary and long-term. A sympathetic stranger on a bus might come to the rescue during an impasse, but a moment of crisis can also be exacerbated by the callousness of those whose compassion we might’ve expected. No Edges illuminates moments of kindness, but its accent lies on the self-work humanity has yet to do—which is complicated by our proneness to illusions. Fatma Shafii’s The Guest and the excerpt from Euphrase Kezilahabi’s Nagona engage with this motif, in respectively lighthearted and oracular tones. In Nagona, the truth is a privy revelation, meant for the chosen and prophesied in riddles. However, one rule is given to the protagonist in no uncertain terms: “Hold onto your soul. That is truly what it is to grow up.” Timo from Mwas Mahugu’s Timo and Kayole’s Chaos is doing exactly that, although in a mundane setting. Having gotten into the risky business of hawking to support his family, Timo recommends street smarts to navigate the complex human networks where violence and indifference are inevitably rampant. Other stories suggest a complete overhaul of human behavior, yearning for a more peaceful future.

The excerpt from Clara Momanyi’s Nakuruto immerses the reader in a kaleidoscope of the eponymous protagonist’s dreams, revealing caves embedded with prehistoric skeletons, forests replete with titanic trees and strange animals, utopian savannas where predation is null and hyenas feed alongside—instead of on—hartebeest. In a narrative that artfully blends the somnambulist’s journeys and the travels in reality, Nakuruto eventually arrives at an area settled by humans, and is struck by the atmosphere of hostility: herdsmen, roaming armed with bows and arrows, instills her with fear. After making her way towards a far-off village, she finds that the paths have all been overgrown; humans “have abandoned the paths—now filled with weeds—and are lost.” Enwisened by her dream travels, Nakuruto makes the first steps to retrace a lost way.

The translators behind No Edges have preserved the unique cadence of every story: each author’s narrative voice is striking and unmistakable. Moreover, the tales all start off with a snippet from the Swahili version, giving the reader a taste of the original. Beautifully translated and rich with interrogations and reminders of our humanity, No Edges is an indispensable read for our increasingly reclusive post-quarantine world.

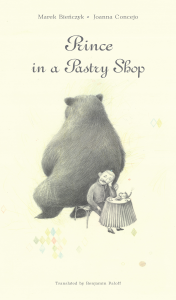

Prince in a Pastry Shop by Marek Bieńczyk, illustrated by Joanna Concejo and translated from the Polish by Benjamin Paloff, Seven Stories Press, 2023

Review by Rachel Landau, Assistant Poetry Editor

Marek Bienczyk and Joanna Concejo’s Prince in a Pastry Shop is a discourse enwreathed in delicate beauty. Over less than forty illustrated pages, two characters, the Not-So-Little Prince and Prickly Pear, spend time together and consume pastry after pastry, all while contemplating the nature of happiness. Translated by Benjamin Paloff into English, this book is philosophical yet gentle; moments of dense, contemplative language are balanced by silent, empty space.

The rich illustrations, identical to those published in the original Polish-language text, are a jaw-dropping feature of this book. Characters are rendered in pencil sketches on a yellow background, with dreamy and timeless facial expressions and shockingly large surroundings. Color is used sparsely amid the pencil—at first only for floral decorations, flowers themselves, and some immense cookies. Eventually, as the narrative proceeds, color creeps into features more proximate to the protagonists, and even Prickly Pear’s hair and sweater become bedazzled in various hues, a pleasant contrast to the monochrome of graphite.

Certainly more weighty than the everyday language of a bakery conversations, the dialogue between Prickly Pear and the Prince comprises almost all of the text in the story; as such, it is noticeable and important that Paloff has rendered their back-and-forth with gentle grace. The ongoing conversation between the two protagonists concerns happiness and its cost, with occasional references to pastries that strive to lighten the mood and remind the reader of where the conversation is taking place. The images—that of happiness, of conversation, of delightful desserts—bleed into each other with much thanks to the translator’s efforts.

Indeed, as the translator of a book with such sparse language and dazzling illustrations, Paloff has successfully endeavored to emphasize subtlety. The language of the Not-So-Little Prince’s philosophy is rather dense and repetitive. Many of the chunks of text in the dialogue are meandering, as can be noted in how the Not-So-Little Prince addresses Prickly Pear towards the start of the story: “Happiness is divine retribution. When you have it, you don’t notice. You don’t think about it at all. You eat your tasty donut or your tasty napoleon in the most superb company I know of, and you’re not even aware that nothing will ever top what’s happening to you right now.”

Between these marathons of puzzling questions and self-doubt come pleasant silences, a chance to breathe and dwell on the illustrations; through them, we are privy to details about the protagonists’ posture and motion that go undescribed in the text. Furthermore, the passages of text are spaced out in such a way that invites the reader to join the protagonists in silent contemplation. After all, the questions that the Not-So-Little Prince is asking are crucial for any of us, as happiness is something we are all supposed to seek.

On that note, this is not the only interpretation of Prince in a Pastry Shop to have appeared in recent years: filmmaker Katarzyna Agopsowocz directed a short film based on the story in 2020. The afterlife of the story’s initial publication, with prizes and cinematic renditions and now a translation into English, confirms that the puzzle of happiness continues to demand investigation. Like the Not-So-Little Prince, it is not uncommon that one encounters disappointment and frustration by the challenges of attaining it.

It also confirms that this is a text worth celebrating with such extensive reproductions. Bienczyk and Concejo, with Paloff as translator, have produced a text for those individuals interested in happiness, but who are not exactly cheerful about the nature of joy. However, the writer, illustrator, and translator are honest, and the text is phenomenally crafted. Much like the donuts and napoleons enjoyed by the Not-So-Little Prince ad Prickly Pear, this book is satiating and sweet.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: