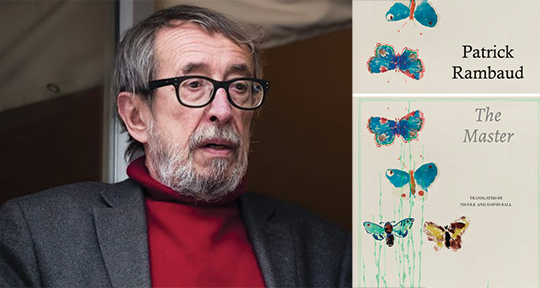

The Master by Patrick Rambaud, translated from the French by David Ball and Nicole Ball, Seagull Books

Patrick Rambaud’s The Master tells the story of the life of Zhuang Zhou, a legendary philosopher, the progenitor of Taoism, and the probable author of the eponymous Zhuangzi, a collection of metaphysical teachings beloved by ancients and moderns alike. Zhuang Zhou lived two and half thousand years ago, only a few centuries removed from the misty limits of recorded history, during the Warring States period, a febrile, fractious time of geopolitical strife and civilisational flourishing. Historical accounts about him are nearly nonexistent, and what little is known of his life we can only glean from the Zhuangzi, whose lessons come in the form of parables supposedly inspired from events in his life.

The life and times of a quasi-mythical master philosopher, so far away in time, so sparsely recorded by contemporary historiography, so enmeshed already in fable and allegory, are ripe for historical fiction: the genre’s usual constraints, born of the need to fictionalise within the bounds of the historical record, become looser as the hard truths of history become more difficult to pin down. Rambaud uses this unusual latitude cleverly, but also with scrupulousness. The Zhuangzi is his source text, and he treats it with immense respect—something clear in all of the literary inventions present in The Master, and clearest of all in Zhuang Zhou himself, his chief creation.

The parables do not mention Zhuang Zhou’s childhood, so Rambaud invents one more or less from scratch. Born into the ascendant, educated middle class, Rambaud’s Zhuang is groomed for the bureaucracy by his father (the so-called Minister for Gifts), who envisions a comfortably parasitic life for his son in the palace in the state of Song. The youthful Zhuang is docile, but quietly eccentric—more curious, more questioning, less venal than his peers, and with an unusual devotion to the Confucian values that supposedly underpin the harmonious functioning of the state: frugality, sobriety, unquestioning obeisance to his betters, magnanimity towards his inferiors. Formative disappointment comes early and brutally for Zhuang: his first taste of palace life—opulent, frivolous, the ruler a puppet to his courtiers—reveals the state to be grotesquely corrupt, with Confucius its cynical veneer.

Zhuang accepts the ugly status quo, but his life takes a turn. The ruler of Song is violently deposed in a palace coup (a perennial occurrence in these volatile times), forcing Zhuang and his family to flee to the neighbouring kingdom of Qi. He lives there for a time among a school of vacuous thinkers, where further disillusionment ensues, before another bloody coup, this time supported by Qi, clears the path for his family’s return home. A career as an official in the new regime awaits him, but desperate by now to escape inane and deadly palace conspiracies, he chooses to work in the countryside, where he peels away the last of his Confucian deference and interrogates his growing disenchantment with human progress. Disillusion sets in definitively with the death of his wife from plague; he slips free of the final constraints of modernity and undertakes to wander China and form his own philosophy, one of radical and uncompromising carefreeness.

As Zhuang matures from quiet sceptic into a genius philosopher errant, the influence of the Zhuangzi comes to dominate The Master. The chapters become episodic and self-contained, with Rambaud borrowing wholesale from the ancient Chinese fables. He does so reverentially; the occasional peripheral riff aside, the contents of the Zhuangzi that appear in The Master are strictly off-limits to his fictionalising—the parables are, in effect, the source material, and are treated with scrupulousness and care. Rambaud fairly lifts anecdotes from the Zhuangzi, keeping intact not only their details but also their parable structures, and slots them into his chronology; it is his way of paying tribute—they are honoured guests in this elaborate palanquin of a narrative. The presence of the parables leaves Rambaud’s account of Zhuang’s life apocryphal and myth-tinged, and the China he roams becomes lurid and fabulistic in turn. It is an intriguing fusion of embellishment and fact; through Rambaud’s contrivances, Zhuang wanders far and wide across a vaguely historical China, and the anecdotes, moulded as they have been into fables and tall stories, are of a piece with Rambaud’s slightly improbable biography—the seams between Zhuang’s adornments and Rambaud’s never show.

Rambaud summons places and figures from the historical record to dot the narrative (fun referents for the nerdy, but also the source of The Master’s vaguely plausible verisimilitude). These are cautionary and grotesque: spoilt kings presiding over fin-de-siècle kingdoms, their courts filled with opulence and grasping mandarins and pointlessly feuding sages. In the countryside, meanwhile, peasants are bovine, brutalised into an unthinking compliance by their rulers, living on grass and nettle soup, and slaughtered almost incidentally by passing bandits. Zhuang comes to despise rich and poor in equal measure, the former for their dissipation, the latter for their mindless acceptance of their fates, and, thus disgusted with the world, takes to the mountains, where he can live as far as possible from human civilisation.

The travels offer samplings of various flavours of human venality, and reinforce Zhuang’s view that the world is sick, obsessed with mortality, and to be escaped from at all costs. Though the Zhuangzi stories are faithfully (even uncritically) re-transmitted in The Master, they never achieve the same reverberance that the Zhuangzi is known for. The problem is that the Zhuangzi, as well as being profound, is also deeply funny. The stories are parables in large part to better satirise the mores of contemporary China; they function equally as jokes, with the moral hiding at the end of the improbable story and jumping out at you like a punchline.

This appears to be a problem not with Rambaud but with Nicole and David Ball. Occasionally, the ghost of a joke hovers into view in the English—the Prime Minister of Song being chosen on his merits as a cook, for example, or the fact that the most virtuous man in all of China is a bandit who eats pâté made from human liver—but such focal absurdities are muffled at every turn by the even, frictionless neutrality of the Balls’ prose; with the absurdity goes any of the pointed wit these episodes might have conveyed. The unchanging tonal evenness has the unfortunate effect of making this China seem more congruent, more historical, more “real” than is healthy for the kind of humour the Zhuangzi delights in and which Rambaud attempts to channel.

The Balls have produced prose that is lucid and often very graceful, well-suited to the frequent evocations of the calmness of nature—Zhuang’s abiding fascination—but fatal to the satire that seems to have once been pervasive. This is a shame, because it deprives us of what you sense to be the full blast of the fun and ingenuity of the French, and is also a serious problem for the “soul” of the novel. In his clever but ultimately scrupulous incorporation of the Zhuangzi, you sense Rambaud holds a deep appreciation for its metaphysical lessons. But without humour to demonstrate its tenets and leaven (or enhance, or hone) the pessimism at its core, the philosophy feels unconvincing and nasty, the lessons reduced to dull, misanthropic brow-beatings from a grumpy old man—for Zhuang Zhou suffers in the absence of humour, too. He acquires the eccentricities of an irascible hermit-philosopher, but with his sense of humour malformed by the prose, his company becomes less and less tolerable, until up in the mountains, his Taoist philosophy fully formed, he reveals a repugnant indifference to human life. Unintentionally perhaps, we are treated to the consequences of transcendence from the mundane concerns of humanity: a near psychopathic indifference to worldly suffering.

It seems a line should be drawn between The Master and its French source. Le Maître is a love letter to Taoism, a finely crafted piece of historical fiction, and a respectful if perhaps uncritical engagement with the Zhuangzi; The Master, having lost even more of the irreverent bite of the original, can often read like an inadvertent critique of its philosophy. And yet—although the absence of humour is significant and damaging, there are still pleasures to be found in this translation: the Balls write well in their chosen mode, the cleverness of certain parables shines through, and the storied life that Rambaud plots for Zhuang Zhou is a joy. Enjoy The Master as a ripping yarn set in a grim, feudal China (up to the point Zhuang’s grumpiness becomes unbearable); but if you want to be touched by the philosophical import, better you bypass The Master and read Zhuang Zhou’s words closer to the source, in the English translations of the Zhuangzi.

Matthew Redman is the digital editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: