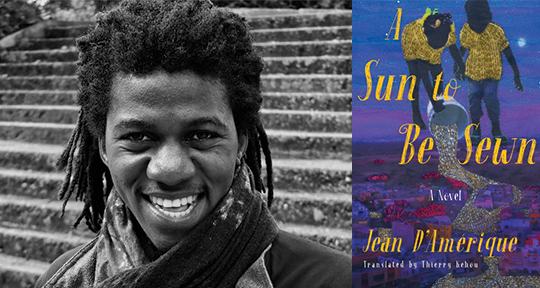

A Sun to be Sewn by Jean D’Amérique, translated from the French by Thierry Kehou, Other Press, 2023

March of 2023 will bring A Sun to be Sewn, a novel by Haitian poet, playwright, and novelist Jean D’Amérique, translated from the French by Thierry Kehou, to bookshelves around the world. D’Amérique explores ravaged landscapes of the city and the heart, delves deep into wounds collective and individual, and parses fragments of hope shored against the ruin of a land ravaged by violence and destitution. Recounting the story of a young Haitian girl fleeing from a cruel prophecy and into the arms of her beloved, treading a path that weaves amidst the dangers of her Port-au-Prince slum, D’Amérique unfolds a panorama of pain and courage, death and desire, telling all in a wounded lyrical style that haunts the reader long after the novel’s end.

A Sun to be Sewn is narrated by a talented young girl, known to the reader as Cracked Head, living in a slum in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Her mother, Orange Blossom, is a prostitute struggling with alcohol addiction, “drowning,” as Cracked Head puts it, “to draw her halo from the abyss.” Her adoptive father, Papa, makes money from various criminal activities, working for a cruel and powerful man known as the Angel of Metal. Cracked Head is no stranger to crime herself, as it provides for survival which would otherwise be impossible. Even so, she lives off of “bread and sweetened water,” anchoring her hope in the image of her beloved: Silence, the daughter of her teacher.

Cracked Head’s yearning for a better future collides with the devastating reality of being situated in a country decimated by inner turmoil and foreign interference. Though finally her lover, Silence departs for New York and Cracked Head is unable to follow after her; severed from the source of her personal meaning, she spends her days in aching reveries, longing for Silence’s company. Meanwhile, her parents lose their lives to the Sisyphean struggle for survival: Orange Blossom finds herself in the wrong place at the wrong time, busy with a client whose assassination had been ordered earlier, and Papa is lynched by the local community for the murder of the Angel of Metal. With nothing left to bind her to her homeland, Cracked Head boards a precariously crowded ferry headed toward the United States, and deep into the journey finds a fateful letter from Silence folded into the pages of a book.

Despite its brevity—being only 160 pages in length—the novel lacks neither range nor subtlety. It relates the lives of children and adults, the rich and the destitute, men and women; moreover, it traverses the wingspan of difficult emotions, such as love and loss, with remarkable ease, exposing the nodes where loss intertwines with rage and love with hopelessness, illuminating distorted human bonds wrought by complicated fates. Thierry Kehou does a mesmerizing job at recasting this beautiful, heartbreaking tale into English: he preserves an almost identical sentence structure, allowing the reader to experience the narrator’s distinct manner of speech, with its biting sarcasm, refrains that take on a new meaning every time they reemerge, and the immense bandwidth of its passion.

Despite its ability to take language to the very limits and endow innocuous words with panoramic potential, the novel also touches on the failure of words in the presence of experiences both devastating and euphoric. This thematic element extends further, revealing how adversity exposes the finitude of the many systems humans use to create meaning. Hampered by both passion and an arduous struggle for survival, Cracked Head time and again fails to compose a letter to her girlfriend, showing how human voices drown in the din of bullets, or are held within to speak on another, better day.

The novel opens exactly thus: Cracked Head struggles to compose a letter to her beloved, crossing out words, “making a kingdom of crumpled papers.” The addressee’s name, Silence, hints at once at the failure of language and the dissolution of its purpose in the face of love—the lovers’ discourse, after all, is that of the body. “Erased is my long road of words,” exclaims the main character when she finally finds herself in the hands of “her moon,” “our bodies are indulging in the best language possible.” The “improbable magic” that calls on the two lovers to coalesce transports them to “a happy abyss,” where the narrator is liberated from her letters and “long sentences.”

Unlike this nonverbal “infinity of pleasure,” the realm of words is far from euphoric—words can be weaponized, used to convey bad news, or to order someone’s assassination, as is often done by the clients of the narrator’s adoptive father and his boss, the Angel of Metal. The narrator is aware of this dangerous link, and physical brutality often fuses with language within the body of metaphors: “The violence flows, savage grammar.” Language is not only adjacent to violence in this novel, but comes to physically embody it: one verbal dagger that reverberates throughout the novel as a refrain, bringing the theme of isolation to a fever pitch, is the future prophesied for the narrator by her adoptive father: You’ll be alone in the great night. It remains unclear whether he utters this out of sadism or disillusionment; it is seen, however, that the damning prophecy is accurate.

The end of the novel witnesses a triumph of language, which ironically results in its collapse: her father’s prophecy is fulfilled, but we do not hear what Cracked Head has to say about Silence’s letter—perhaps, after that point, she has nothing to say at all. After 159 pages of her rebellious, elegiac monologue, in which she not only relates a story, but indulges in it, stretching its already formidable emotional and visual capacity to the utmost, her silence is deafening . . . Here, it’s important to observe that the novel’s treatment of language, as a system of generating and preserving meaning, also extends to other such systems—religion and personal histories, for instance. Showing time and again how systems of meaning falter when physical bodies become trapped in cycles of violence and destitution powerfully conveys the impact of personal and collective tragedy, which underlies the narrative.

One such source of meaning, the millenarian utopia, is poignantly dethroned by the narrator early on, as a “‘soon’ that is becoming increasingly longer.” Even its fulfillment becomes a grim image when she touches on the system hidden beneath this dream: “. . . people will end up as robots, condemned to join hands and glorify a pope more despotic than the one on earth.” Another sense-making system whose solidity is shattered are personal histories: Cracked Head refuses to commit to believing the story about the predecessor of the Angel of Metal, who had allegedly taken his own life to avoid fatherhood. “Everything is as true as it’s false in this country, it depends on the mouth that gives, it depends on the ear that receives . . . The legend mutates over the days but no one knows how to establish a link with any truth.” On other occasions, she rebels against faith in the education system, being “taken with the school of life.” The closer one looks, the more falsifications and mythologies emerge in the space she occupies: Papa is not her real father, the house she lives in isn’t a home, but a “roof that witnesses the parade of our actions, our failed acts, our easy sorrows and our difficult pleasures.” Politicians routinely take bribes and rig elections, suppressing protests with brutal force.

In such a space, there remains nothing to hold on to, no meaning to make from the losses that follow one another in a merciless crescendo. The novel skillfully brings home this escalation of tragedy both through the movement of plot and the deconstruction of language and other sources of meaning against the backdrop of social and economic turmoil. However, this treacherous parade of things and people that refuse to embody the concepts they allegedly represent extends outwards, outside of the novel’s vision of Haiti: towards the end of the novel we meet Half-Blood, a man who had lived in the United States since he was five years old, deported from the ‘land of the free’ for selling marijuana, exiled by “a social environment that fears more than anything the smell of this thing that couldn’t be more natural.” He is sent to Haiti, “where he had no bearings and whose language had escaped him a long time ago.” Justice isn’t the only thing put into question by this moment: identity itself is shown to be fluid, definable by those in positions of power. The reader, then, is faced with an uncomfortable question: Is faith in meaning a privilege of those shielded from adversity?

Sofija Popovska is currently studying for a master’s degree in Comparative Literature at the Georg-August University of Göttingen. Her first poetry collection, Faces in the Crowd, was published in 2021 in North Macedonia. Her other work has been featured in online publications such as Circumference Magazine and Litlog, among others.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: