Happy Friday, friends! Cue shock and awe at the passage of time: February is almost over, and soon we’ll be plucking daffodils in springtime fields. Feel like a summer road trip? Take cues from Norwegian literary bad boy and memoirist Karl Ove Knausgaard’s road trip across the United States (one of his goals is to go without speaking to other Americans—go figure). Here’s the first part of the Saga, in exhaustive detail and translated by Ingvild Burkley. READ MORE…

Monthly Archives: February 2015

Discovering Terroir

In Part 4 of her series on food and literature, Nina Sparling talks terroir—in France, and in Dany Laferrière's Haiti

The word is known: terroir. It has become familiar in English, borrowed from French instead of translated. The word means soil or land. To discuss the terroir of a region, of a plot of land, imbues the subject with meaning and history: terroir is tradition.

Terroir isn’t about being close to where your food grows as a consumer but rather describes the experience of place. It describes the taste of a place. Understanding it comes from the experience of being from and living somewhere. There is an understanding in France that specific foods come from particular places. Every other item in a market is a produit du terroir, de somewhere: poulet de Brest, fleur de sel de Guerande, crottin de Chavignol, and so on. Terroir also points to an obsession with authenticity and tradition—one could argue that the worst of French nationalism and identity expresses itself in terroir. Indeed, exclusion and tradition are both part of its usage in France.

Yet the term also values the communities and weathered rhythms of a place in a more general sense. Food and people come from somewhere: both are rooted. This, the understanding that food and eating are basic and essential to how we inhabit the world—that personality and society are connected to the land and what it produces—is where terroir pulls me in. Dany Laferrière illustrates this aspect of terroir in his novel Pays sans chapeau. The work is fiction and autobiography, part memory and part story. In it, the narrator returns home to Port-au-Prince after twenty years living in Montreal. The city is in disarray, grappling with political instability and violence. He returns to his mother’s house, where the most vivid scenes and memories occur over plates of shared food.

This Monster, the Volk

At the Pegida demonstrations, the soul of Dresden has been revealed: reckoning with the mentality of my native city

Monika Cassel translates Durs Grünbein’s op-ed, which appeared on the front page of Die Zeit’s weekly magazine on February 12, 2015, the day before the 70th anniversary of Dresden’s bombing.

Every year, the city I was born in falls again. On the one hand this is a ritual (of commemoration), and on the other hand it is a reality (of history). All over the world, people know what happened to Dresden in February 1945, just before the great turning point in history when Germany was given the opportunity to better itself. The city lost nearly everything that had once made her charming and was from then on condemned to live on, severely handicapped, hideously deformed, and humiliated. Where once courtly splendor and stone-hewed bourgeois pride had delighted the eye, now desolate wastelands unfolded as I wandered through my city as a child. It is hard to imagine that this was where Casanova contracted a venereal disease and Frederick the Great, when he was still the crown prince, lost his virginity. According to legend, one of the delectable ladies-in-waiting pulled him through a concealed door and initiated him into the Saxon mysteries of love. I still remember imagining the Marquis de Sade visiting the city on the Elbe. In one thing, at least, historians are in agreement: what was supposedly once the most beautiful Italian city north of the Alps was a paradise on earth for all of the libertines of aristocratic Europe.

But it all turned out differently. Lately I have seen a monster in Dresden—it calls itself das Volk (the People) and thinks it has justice on its side. “We are the Volk,” it yells, shamelessly, and it cuts anyone off mid-sentence who dares disagree. It presumes to know who belongs and who does not. It intimidates those from foreign lands because—in the extremity of their plight—they have nowhere else to go, those who come in search of a better life. I can identify with these asylum-seekers. I was once a person who felt trapped in his country, in his native city. Who wanted to escape from a closed society—precisely the kind some wish we could return to again. Was I an economic refugee, driven by political dissent against the system that had planned my whole life for me, was it a yearning for foreign cultures, or all of these? Who can say?

Proust Questionnaire: Tim Wilkinson

...a "Lydia Davis" questionnaire for Hungarian-language translator Tim Wilkinson

Tim Wilkinson (b. 1947) grew up in Sheffield, S. Yorks., but has lived most his adult life in London. He is the primary English translator of Hungarian writer Imre Kertész (titles including Fatelessness, Fiasco, Kaddish for an Unborn Child, Liquidation, Detective Story, The Pathseeker and Dossier K) and, more recently, Miklós Szentkuthy (Marginalia on Casanova, Towards the One and Only Metaphor), among others, as well as shorter works by a wide range of other contemporary Hungarian-language authors. Fatelessness was awarded the PEN Club/Book of the Month Translation Prize for 2005.

Q: How did you learn your foreign language, and how did you begin working as a literary translator?

A: I learned Hungarian “on the hoof,” mainly by moving to Budapest around Easter 1970 and marrying the girl with whom I had by then fallen in love, having made several trips there since 1964. I might add that I sort of picked up German in much the same way (minus the love complications), by taking up a job in Switzerland, 20 years later. Contact with speakers of a language is, for me, the important feature, just as it is with small children… The strictly “literary” translation work only really came about ten years ago, after I had been translating a fairly wide range of non-fiction (mostly with a pronounced historical flavor) as an add-on to my main job (which was in an altogether different field and had little or nothing to do with translation). READ MORE…

In Review: “Rabbit Back Literature Society”

On a meta-writerly thriller from Finland: "Jääskeläinen’s exploration of the magpie habit of a writer is thorough and complex."

The fictional Finnish town of Rabbit Back is the setting for Pasi Ilmari Jääskeläinen’s The Rabbit Back Literature Society (tr. Lola Rogers), a strange chimera of snow-bound noir and creeping surrealism that reveals itself with the unassuming gestures of a children’s book.

Rabbit Back is the home of the bestselling (and reclusive) children’s book author Laura White. White’s Creatureville books, widely lauded for their striking treatment of local myths, have brought worldwide recognition to the town and to the coterie of nine protégés she hand-selected at an early age to be the members of her Rabbit Back Literature Society—young men and women who have, by the time of the events in the book, matured into the upper ranks of the Finnish literary scene. READ MORE…

Happy friday, translation friends! We frequently post all sorts of dispatches on the blog—when the Asymptote family stretches far and wide to connect with other readers all across the globe—but rarely does our team encounter literature under threat. Here’s a report on the Karachi literary festival, in which the Guardian contends that “books really are a matter of life and death.” (they aren’t elsewhere, either?!). And in Egypt, good news for freedom of the press: a high court has granted bail to two Al Jazeera journalists. And Guernica reports on another country in conflict struggling to find voice on the international stage: Syria in image. READ MORE…

Take a look at “Steaua”—Asymptote’s Romanian Partner Journal

An in-depth introduction to Asymptote's newest partner journal, "Steaua"

A few weeks ago, we at Asymptote blog highlighted the importance of vibrant, youthful literary journals—in exchange. In that post, we featured Fleur des Lettres, from Hong Kong, and the fruitful artistic encounters that partnership has yielded.

This week, we highlight another budding intertextual friendship, namely that one between Asymptote and Romanian lit-mag Steaua. Contemporary literature is scarce and relies heavily on exchange. This could hardly be truer than with international literature—where impediments like translation, marketing, and the consumer publishing culture risk obscuring gems we should all be watching out for. Here’s Romanian editor-at-large MARGENTO’s take on what looks to be the beginning of a long and fruitful cross-journal collaboration. READ MORE…

In Conversation: Portuguese translator Alison Entrekin

Do you use a special filter to replace whatever has been lost, or do you leave the photograph unadulterated?

Eric Becker: Before we get into more details about Brazilian literature itself—how is it you came to literary translation, and why Brazil?

AE: As is probably the case with most literary translators, I didn’t just wake up one morning and think “I want to be a literary translator.” Rather, it came to me slowly. I had originally studied Creative Writing at university in Australia, and wanted to be a writer. But fresh out of university, I married a Brazilian and moved to Brazil. I did what many foreigners do when they first arrive here: I taught English. But it wasn’t really what I wanted to be doing. I realized I had a flair for language and did a course in translation, with the sole intent of becoming a literary translator, even though I had read barely any Brazilian literature before that. I just had a hunch that the creative writing and translation skills could be a useful pairing.

EB: You’ve been translating now for about a decade and a half. What is it you’ve learned or what has changed in your practice during that time?

AE: Well, apart from settling into a way of working that works for me, I’ve developed countless theories about the differences between Portuguese and English, between Brazilian literature and English literatures. In fact, with every new book I translate, I either further one of my pet theories a little or more, or develop a completely new one.

For example, I am endlessly fascinated by how certain literary aesthetics can be received so differently from one culture to the next. The very grammar of the Portuguese language, and the culture in which it is embedded, have given rise to such different perceptions of what constitutes “good style.” Sentences that are witty in Portuguese can come across as pedantic or convoluted in English.

Translation Tuesday: “The Mouse” by Regina Ullmann

An excerpt from The Country Road, translated by Kurt Beals

Death was prepared in the form of a trap. But before its time finally came, the mouse would have to gnaw through the wall that led into my bed-chamber. It would have to gnaw through a long and narrow passage, and gnaw through my sleep.

Sometimes I pounded on the bed with my fist, frightening myself with the way that its thunder rolled over everything imaginable in the night. And I thought I could sense that the mouse felt this fear, too. But before this wave of fright could roll gently into peace, that same quiet gnawing could be heard again from afar. It was so quiet that it was audible only to someone alone and left to himself in a house by a moonlit field on the edge of a forest. He guards himself like his own hunting dog, and even when he is asleep he will hear any approaching danger. He is like fog, when it is dark, the fog that seems to live in its own light. He is like the rain, far and wide, high and distant, in the heavens and on earth. How could he fail to notice the gnawing of a mouse, when that activity returns again to itself. He feels it in his blood. So once again I lit my candle, the bane of all four-footed intruders. But the candle didn’t spread its angel wings as it had in other nights, arching them over the dark abyss of fear, becoming a spirit of the shadows, the better to offer its light . . . Instead it suddenly betrayed me to my enemy, becoming a sort of gnawing creature itself, there in its candlestick. It ate away at my sleep, and the mouse did not fear it.

Editor-at-Large Testimonial: Rahul Soni

Our India editor-at-large Rahul Soni looks at his Asymptote favorites—and muses on what he hopes to see in issues to come

It’s hard to choose just one piece that I’ve been proud to introduce to Asymptote readers—as editor, aren’t I supposed to be proud of everything selected for inclusion?

But if pressed, I’d perhaps name Banaphool’s Nawab Sahib, translated from the Bengali by Arunava Sinha. Banaphool (1899-1979) was an extremely prolific writer, with 586 short stories, 60 novels, five plays, an autobiography, numerous essays, and thousands of poems to his credit—apart from being a painter and practicing doctor. And as the story in question reveals, his fame is not simply a matter of numbers—Banaphool possessed a keen eye for structure and pacing, the telling detail, and for human absurdity.

Banaphool was a great literary craftsman who operated in a breathtaking range of registers. Still, though the master of many tones, Banaphool consistently invited his own, unique sensibility into his writing. And he may very well have invented the genre of the very short story—often less than a page in length—a form that is now finding currency under the nomenclature of “flash fiction”. I’m grateful to Arunava Sinha, without whose lovely translations we of the non-Bengali-speaking/reading world may have had to wait much longer to be introduced to this great world author.

Looking forward, I am most excited about bringing to our readers (and an audience of readers worldwide)—a novel(la) by one of the foremost men-of-letters in Hindi named Dharamvir Bharati, called Suraj ka Satvan Ghoda (which translates to The Seventh Horse of the Sun).

Published in 1952, it is what might be called an experimental novel, incorporating elements from “folk” storytelling into a novel-in-variation-form structure (to use, anachronistically, Milan Kundera’s term), and is written in a whimsically and colloquially, with an ironic take on the Marxist politics that has been (and still is) so dominant in Hindi Literature.

Sui generis: it is unique in Hindi literature (and, indeed, it is singular in the author’s own oeuvre as well), a far cry from conventional European modes of novel-writing. In terms of the history of the novel, The Seventh Horse of the Sun stands as a signpost to one of the roads not taken. It was adapted into a movie of the same name by Shyam Benegal in 1993 —one of the most singular masterpieces of Hindi cinema. Shamefully enough, there is but one translation of the novel, one lacking in both quality and distribution. This is clearly a disservice to the text, the author and the readers. It is my hope that I will be able to, some day, secure permission for a fresh translation and present it to our readers.

Happy Friday-the-thirteenth, everybody! Let’s hope the unlucky date doesn’t squash whatever romantic plans you may have for Valentine’s Day tomorrow….

First Scandinavian crime novels took the translation world by storm. Now it’s Brazil‘s turn. At the Globe and Mail, Chris Frey argues that Brazilian author Daniel Galera’s latest novel, Blood-Drenched Beard (translated by Alison Entrekin), is poised to launch a veritable torrent of popular Brazilian literature in English translation. And so that you may be on the pulse for years to come: announcing the Literary Hub, future center for all (English-language) things book-and-web-based. READ MORE…

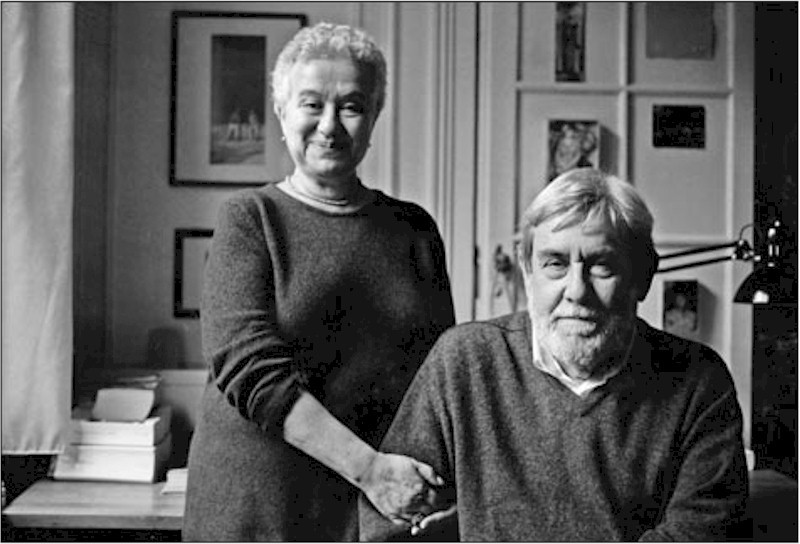

Larissa and Richard Translate a Menu

What happens when two of the greats conspire to translate a dinner menu?

“We discuss endlessly and sometimes it becomes a nuisance because we return to it again and again even after the manuscript goes off. But we really don’t quarrel. It would be much more interesting if we did.”

— Larissa Volokhonsky, in an interview with The Wall Street Journal

Over the last several decades, the married translation team of Richard Pevear (native English speaker) and Larissa Volokhonsky (native Russian speaker) have proceeded through the masterworks of Russian literature from Dostoyevsky to Pasternak with ruthless efficiency, skill, and finesse. But one morning, the couple embarked on an audacious new project that threatened to tear them apart: that of the Sandovar restaurant. (What follows is wholly invented, of course.) READ MORE…

For all you graphic novel (in translation!) fans: contributing editor Adrian Nathan West translated A Human Act, about the Second Mafia War, by Manfredi Giffone, Fabrizio Longo, and Alessandro Parodi for Words Without Borders. And in Brouillon, he discusses the challenges of translating alliteration in Pere Gimferrer’s Fortuny; in this case, his search through the Oxford English Dictionary leads him to “Vauntmure,” “a beautiful, obsolete word” and a type of fortification wall.

Transaction Press has just published past contributor John Taylor’s collection of essays A Little Tour through European Poetry. It follows John Taylor’s earlier volume Into the Heart of European Poetry and discusses a great number of translations, including poetry from the Czech Republic, Denmark, Lithuania, Albania, Romania, Turkey, and Portugal. It even presents an important poet born in the Chuvash Republic—not to be missed!

In November, Joshua Craze, nonfiction editor, published an excerpt from his forthcoming novel, Redacted Mind, with New York’s New Museum as part of its center for translation. The center previously hosted another book project of his, How To Do Things Without Words. In his introduction to Craze’s work, Omar Berrada, co-director of Dar Al-Ma’mûn, said, “In most cases, looking for whatever text lies behind the redactions is bound to fail. Instead, Craze proposes to examine what the redaction performs. Rather than uncovering the secret beneath the mask, understanding depends on looking closely at the surface itself. It is an art of description, of listening to surfaces.”

Publisher Profile: Restless Books

"Restless was conceived in a moment when decisive transformations were taking place."

Restless Books is a digital-first publishing initiative spearheaded by Ilan Stavans, the Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. Stavans is also a writer and cofounder of the Great Books Summer Program at Amherst, Stanford, and Oxford. We spoke via Skype about his books, which “reflect the restlessness of our multiform lives.”

Frances Riddle: How was Restless Books born?

Ilan Stavans: Restless was conceived in a moment when decisive transformations were taking place. Booksellers were shrinking in size; big publishers were limiting the number of books coming from different countries, from different languages. Restless came out of a response to the limited exposure an American reader has to international fiction. We aim to translate great work from a variety of languages. That was and is our mission—to compensate for the commercial way of thinking the big publishers have in New York City. We are a mid-sized publisher, but our goal is to help internationalize the landscape of American literature as much as possible. The Press aims to publish fiction, non-fiction, and poetry dealing with restlessness as a condition.

FR: Was this focus on movement—restlessness—inspired by your own immigrant experience? READ MORE…