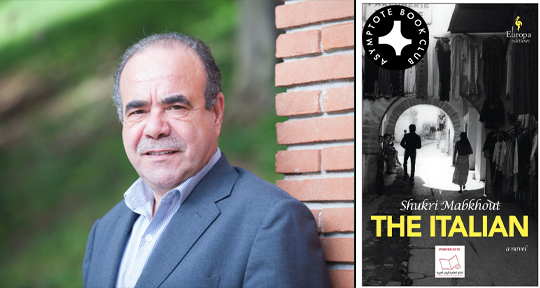

Shukri Mabkhout’s The Italian, an epic tale of romance and revolution in the tumult of 1980s and 1990s Tunisia, won the prestigious International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2015, making it the first Tunisian novel to achieve this accolade. As our Book Club selection for the month of October, Mabkhout’s wide-ranging novel gives an intricate look into the inner workings of young idealism under dictatorship, with all the brilliance and hardship that comes with hope. In the following interview, Rachel Stanyon spoke live to the translators of The Italian, Karen McNeil and Miled Faiza, on their working process, the representation of women in a literary scene dominated by men, and working towards a greater representation of Tunisian literature in the Arab world.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Rachel Stanyon (RS): I’ve read in an interview on Arablit.org that your translation strategy involves Miled first doing a quite literal pass, and Karen then revising the draft for idioms, flow, etc. Did your translation of The Italian also involve a dialogue with the author, Shukri Mabkhout?

Karen McNeil (KM): Yes, it did, and that was really Miled’s role throughout the project. During both the translation and revision, we contacted Shukri a lot. There were sometimes words that we had no idea about! Miled was killing himself looking for this one word in every dictionary imaginable, and it turned out it was just this particular word that Shukri’s family uses, and probably no one else in Tunisia does. There are always these little idiosyncrasies. All the translations I’ve done have been in circumstances where we could work with the author—I almost can’t imagine it otherwise; there are just so many difficulties that require follow-up questions.

Miled Faiza (MF): Shukri was very supportive, which was really nice. I don’t think there are many passages that are difficult in the novel; we just wanted to be as accurate as possible—even with small things, such as recipes. I am from the central east of the country, and he’s from the north, the capital. Tunisia is a very small and culturally homogenous country, but there are a few small things that Shukri probably grew up with: what they cooked at home, or the clothes they wore, or things that are very specific to Tunis, the capital. He was very helpful with my queries about those specific questions.

I was able to find the word Karen mentioned in an Arabic dictionary; Lisan al-Arab, one of the oldest and largest dictionaries in the world, has an entire passage on it. But the meaning didn’t work in the context, so it was driving me crazy. I sent him a message, and he told me: “Oh, I’m sorry, that is a French word that my father used to say.” So it was a word very specific to his family, and he just threw it in there.

RS: The language of The Italian tends to be quite descriptive, and involves a lot of very detailed information on things like philosophy, Tunisian cuisine, or the process of publishing a newspaper. Miled, I’m particularly interested in how you, as a poet, found translating what I found sometimes to be quite dry, academic passages. Did these aspects of the translation pose any problems for either of you, and, in general, what were the biggest challenges for you in translating this novel?

MF: Our great friend, Addie Leak, edited this book and worked with us very closely—it’s really important to always mention her because she is amazing. I asked her: “How did you find the novel? What do you feel about the section on the political history of Tunisia?” She told me she loved it, which was a little surprising. Certain sections, especially those with a lot of details about the union and the different branches of Tunisian student activists, I found dry—and maybe it would have been possible to just summarise and get rid of a lot of it. But that’s my point of view as a Tunisian. I was more interested in the story of Abdel Nasser and Zeina, with the background of everything going on in Tunisia. I thought the very small details—of every congress and every meeting, important dates from Tunisian history—were not that interesting; they were a little bit dry for me.

KM: I think the parts when Abdel Nasser is at university, and especially the philosophical points, are actually even drier in Arabic. It was very challenging to make that flow in English, because it’s very much like a lecture or a philosophy textbook. It was difficult to render that in English without doing harm to the integrity of the original. Even though it was painful while I was doing it, though, with a little perspective I think I can appreciate why it goes on for so long. In the structure of the novel, that activism was Abdel Nasser’s whole life, but once he graduates from university, one realises that all the things the university students are doing, thinking that they’re changing the country—none of it really matters. I think it captures Abdel Nasser’s viewpoint of it being very important. READ MORE…