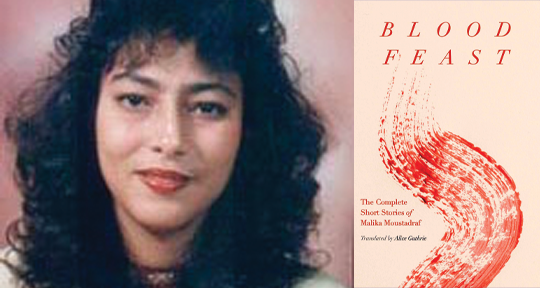

Blood Feast: The Complete Short Stories of Malika Moustadraf, translated from the Arabic by Alice Guthrie, The Feminist Press, 2022

More than a decade after the original publication of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley infamously called the book her “hideous progeny.” A whole critical tradition was born in the shadow of that phrase, obsessively sewn together by the umbilical connections between writing, motherhood and the monstrosity of autobiography; no one could forget that the complications of Shelley’s birth had literally sent her own mother—the pioneering English feminist Mary Wollstonecraft—to an untimely death.

Like giving birth, writing exacts an extraordinary sacrifice in order to grant the gift of life to another. It’s difficult to imagine a more tragic illustration than the story of Moroccan cult feminist icon, Malika Moustadraf. Debilitated by chronic kidney illness but dogged and uncompromising in her devotion to her craft, Moustadraf skipped rounds of essential medication to fund her first publication. This literary progeny consumed her—heart, soul, and kidney; still she insisted, “writing is a kind of sedative for the pain I live with.”

Every word she set down on the page sustained as much as it killed her, as Alice Guthrie tells us in her tender and comprehensive translator’s note, appended to her crisp rendering of Blood Feast: The Complete Short Stories of Malika Moustadraf (issued in the UK by Saqi Books under the title Something Strange, Like Hunger). Beyond its ambitious sweep of contextual detail, Guthrie’s essay represents a loving tribute to Moustadraf’s tempestuous and painfully ephemeral existence in the karians of Casablanca—a monument to all the work she could have written if not for the overlapping violences of the systems that failed her, one after the other.

Karian, a term unique to Casablanca, is cleverly left untranslated by Guthrie and glossed as impoverished neighbourhoods—with “unregulated improvised residential structures,” “often inhabited by recent migrants to the city from rural areas.” Fringed by a context of Sufi marabouts and witchcraft, these spaces are rife with djinn and black magic curses inflicting impotence, lovesickness, and malady on the integrity of bodies. Throughout Blood Feast, Guthrie’s familiarity with the rituals, superstitions, and slang of the region are not simply evident in the cadences of her translation, but further substantiated by the specific Arabic and Darija expressions she opts not to translate. READ MORE…