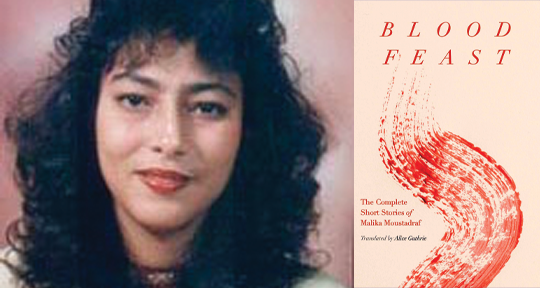

Blood Feast: The Complete Short Stories of Malika Moustadraf, translated from the Arabic by Alice Guthrie, The Feminist Press, 2022

More than a decade after the original publication of Frankenstein, Mary Shelley infamously called the book her “hideous progeny.” A whole critical tradition was born in the shadow of that phrase, obsessively sewn together by the umbilical connections between writing, motherhood and the monstrosity of autobiography; no one could forget that the complications of Shelley’s birth had literally sent her own mother—the pioneering English feminist Mary Wollstonecraft—to an untimely death.

Like giving birth, writing exacts an extraordinary sacrifice in order to grant the gift of life to another. It’s difficult to imagine a more tragic illustration than the story of Moroccan cult feminist icon, Malika Moustadraf. Debilitated by chronic kidney illness but dogged and uncompromising in her devotion to her craft, Moustadraf skipped rounds of essential medication to fund her first publication. This literary progeny consumed her—heart, soul, and kidney; still she insisted, “writing is a kind of sedative for the pain I live with.”

Every word she set down on the page sustained as much as it killed her, as Alice Guthrie tells us in her tender and comprehensive translator’s note, appended to her crisp rendering of Blood Feast: The Complete Short Stories of Malika Moustadraf (issued in the UK by Saqi Books under the title Something Strange, Like Hunger). Beyond its ambitious sweep of contextual detail, Guthrie’s essay represents a loving tribute to Moustadraf’s tempestuous and painfully ephemeral existence in the karians of Casablanca—a monument to all the work she could have written if not for the overlapping violences of the systems that failed her, one after the other.

Karian, a term unique to Casablanca, is cleverly left untranslated by Guthrie and glossed as impoverished neighbourhoods—with “unregulated improvised residential structures,” “often inhabited by recent migrants to the city from rural areas.” Fringed by a context of Sufi marabouts and witchcraft, these spaces are rife with djinn and black magic curses inflicting impotence, lovesickness, and malady on the integrity of bodies. Throughout Blood Feast, Guthrie’s familiarity with the rituals, superstitions, and slang of the region are not simply evident in the cadences of her translation, but further substantiated by the specific Arabic and Darija expressions she opts not to translate.

A “complete” collection of any genre evokes long, fruitful careers bound in elaborate tomes, and so it was with some shock that I realised the compactness of this volume, only slightly surpassing a hundred pages. Holding the slimness of Blood Feast in my hands, I thought of Guthrie’s painstaking labour, salvaging out-of-print stories that used to exist only as low-quality scans circulating online between fans. I thought of how Moustadraf stole slivers of time to write in between dialysis sessions, turning potential novels into short stories because she was not sure how long more she had to live. I thought, more viscerally, of what language must mean to someone like Moustadraf, so willing to sacrifice her body for the sake of honing a voice that would outlive her mortal flesh.

And how precious, how raw and mordant her voice is, poised with its serrated edge to slice through the obfuscations and lies of a patriarchy buttressed by institutionalised religion. Note the matter-of-factness with which the narrator of “Thirty-Six” scripts her father’s actions after observing him underpaying a sex worker he has brought home and flinging her belongings out of the window:

I can guess what will happen next: he’ll go into the bathroom, wash, then he’ll turn toward Mecca and say, “I prostrate myself with holy intention, offering an extra prayer to Allah.” Every Saturday it’s basically the same story on loop.

So much of Moustadraf’s unflinching collection finds its boldness and mercurial candour precisely in the repetition of such banality. Gendered double standards are ubiquitous in the stories, but perhaps most bitingly perceptible as the burden of tradition in “Raving”:

When I said to my husband, I want you, he said, You are badly brought up . . . aren’t you ashamed to talk that way? The next day he said to me, I want you. I said to him, You are badly brought up . . . aren’t you ashamed to talk that way? He laughed stupidly. This is my right—as granted to me by my religion and by my forefathers.

That word, “stupidly,” really exerts its gravity here; it echoes the automatic, unthinking, and inherited ways in which privilege is exercised at the expense of another’s oppression. While some writers might be known for felicitous turns of phrase or the well-placed semicolon, I find Moustadraf most exceptional in the cinematic simplicity of her vignettes.

Vignettes, as building blocks of Moustadraf’s narrative, are wielded to strip away at illusions of respectability. Through them, we learn that nothing will change in this world—and neither is there reason to believe it will, as long as the men that populate it continue to laugh with impunity at the violence so casually inflicted on their wives and daughters. At its most egregious, domestic abuse becomes mistaken for a signifier of love. “A woman loves an evening beating from time to time,” the odious narrator of “A Day in the Life of a Married Man” rationalises:

And when she complains about it to her neighbour, don’t you believe her cries of misery. She’s just doing that to spite her neighbour, as an indirect way of telling her, ‘My husband hits me, therefore he cares about me.’

To whom is he addressing this twisted wisdom, if wisdom it can be called? A circumspect italicised warning rounds off the piece: “Note: don’t try this prescription with all women,” immediately assuming the ironic resonances of medicinal promise. But for what disease? And who gets to diagnose it? Inflected by our awareness of the privatised medical institutions with which Moustadraf was forced to grapple, this monologue implicates and indicts all the oppressive social systems that sicken the very bodies they claim to heal.

The “feast” of the title story, threaded through by a dialogue between patients in the same dialysis centre, alludes to exactly that slow misery of “dying in instalments over the course of months and years.” “Death will steal in through your pores; it’ll eat into your bones and your chest and your heart, and eat from the same plate as you,” the more seasoned of the two promises the newcomer. Apart from this grotesque cornucopia, the frequency with which anatomical parts are compared to food, albeit apropos, never loses its alarming charge: a breast is “like a fried pepper, limp and revolting”; a repulsive body is likened to “some disgusting piece of food long past its expiration date”; someone with the power to “pull some strings” for personal advantage is “the whiff of fat on the cleaver.”

In the monotony of suffering, any vestigial traces of despair or resignation have been wiped out, replaced by a bland indifference—“an indifference so extreme it borders on cruelty,” as one story has it. “Delusion” unfolds in a kind of purgatorial circularity, with the lascivious male protagonist unleashing vituperations at his family. His sister has married a European and abandoned him in the impoverished backwaters of Morocco; his parents are guilty of the most primordial crime of bringing him into this “rotten world.” The story opens with him leaving the house “cursing everything at the top of the lungs”; the same phrase resurfaces at the story’s conclusion, trailing off in tired ellipses as he returns to a life he detests.

Where the men in Blood Feast appear largely static, trapped in the amber of their misogyny, Moustadraf’s women must negotiate and often struggle to elude their petrifying grasp. This is precisely what foregrounds and intensifies the glimmers of strategy, freedom, and solidarity between them as they wedge open unanticipated possibilities. The mother of the first story “The Ruse”—one of the most memorable—is scandalised by the discovery that her daughter has been working all along at a brothel. Furious disavowal is quickly sublimated into a desperate resourcefulness, as they scramble to avert the imminent crisis of the daughter’s marriage: together with a concerned sister, the mother plots to send her wayward child for “hymen restoration” so that she will be “like new.” Fretted over ceaselessly but bodily absent throughout, the daughter emerges into visibility only through her blood-spotted underwear, paraded as triumphant testimony to her virginity and innocence.

Elsewhere, Moustadraf casts her eye on the variegated colours and textures of female desire, otherwise demonised and maimed by constraint. When Moustadraf was writing, the Internet had just begun to burgeon, and this preliminary emancipation of online chatrooms intersects with a wish for mobility in the final few stories. In “Housefly,” a woman flirts with anonymous men online by way of literary allusions, as if only in others’ fictions can she stitch together a coherent image of herself. Momentarily distracted by her caterwauling baby, she entertains murderous fantasies of asphyxiating him in a lethal hug. All windows of escape close upon her husband’s return, ushering in “a heart-shrinking gloom” that shrouds her, like a pall, in the unimaginative narrowness of reality.

Others have a much more cramped margin of choice. The jilted wife of “Woman: A Djellaba and a Packet of Milk,” deprived of shelter and sustenance, sees “a piece of meat . . . sitting opposite [her], pretending to read a newspaper.” This wry, poignant description would be a more hilarious witticism about carnality and sexual appetite if it did not also remind us of the woman’s, and her baby’s, hunger. She picks a “wilted rose” and fiddles with it until it “whimpers” between her fingers, pondering whether or not to follow, and to be at the mercy of, this ogling stranger.

One of the most outstanding pieces of Moustadraf’s collection—remarkable for its portrayal as for its rarity in Arabic literature—might be “Just Different,” a story that ventriloquises an intersex, or gender nonconforming, character who recalls a childhood of trauma and abuse, shut out of legibility in the binary categories of grammar and religion. Their father physically assaults them with a Qur’an; teachers label them devil’s spawn; both the men’s and women’s hammams refuse them entry. Yet beneath the horror is an underlying coolness, dignity, and humour that I have come to associate with Moustadraf’s singular, radical voice:

After several appointments, a lot of chat and money, and a few tests, [the doctor] informed me of various things that I couldn’t really comprehend: hormones, genes, chromosomes. In the end he told me that I simply needed to accept my body as it was. What a genius!

Moustadraf, in a rare interview, outlined her desire to “inter” those who “tyrannised” her “between the pages of a book.” Diminished by poverty and a heartless state machinery that denied her the care she needed, she may as well have been referring to the brutal facts of her own biography in giving one of her characters the line, “I needed to silence the cry of my body.” But silence it she does not, and will not. What is it, if not her body, that cries out through the wound—the gaping mouth of these words, to which she gave all of herself?

Alex Tan studied comparative literature at Columbia University and is currently assistant editor (fiction) at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: